When I was young and, presumably, far more bloodthirsty than I am today, I loved horror movies. I still watch The Thing at least once a year, and if anyone was interested, I could from memory describe An American Werewolf In London on a shot by shot basis.

The ‘80s were a grand time to be a kid in love with horror. I could dabble via videocassette in the bleak realism of the ‘70s resurgence in the genre while enjoying the more advanced special effects and increasing sense of humor and lunacy that blossomed in the ‘80s. Movies like Re-Animator, Evil Dead II, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Videodrome, Return of The Living Dead, From Beyond, The Fly, etc., etc., will always have a soft spot in my movie-loving heart.

Then there was Creepshow (’82). As a huge Stephen King fan in my pre-teen days, I adored Creepshow (written by King, directed by George Romero), an anthology of five scary, creepy, weird, or, in the case of King’s star performance as Jordy Verrill, goofy, horror shorts, inspired by and imitative of old EC Comics, in whose stories everyone gets exactly what’s coming to them.

I don’t like gore for the sake of gore, killing for the sake of killing. The co-called “torture porn” genre ain’t my thing. I’ve been told Saw and its sequels have something deeper going on, but I’ve yet to bother finding out. Eli Roth leaves me cold. Cabin Fever felt both derivative and insulting to the movies it ripped off. On the other hand, I appreciated the nuttiness of Cabin In The Woods. Though any meaning in its madness was terribly muddled by the end (to the point where one wondered if its creators understood the horror tropes they were upending (a post for another day)), it still had a lot of marvelously creative moments.

As for “found footage” haunted house flicks, the less said the better.

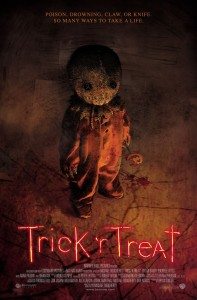

Which is a long way of explaining why I missed out on the ’07 halloween anthology Trick ‘r Treat. Barely released in theaters, it slid right by me. But it’s grown in stature so hugely since then that a sequel has been announced. It’s officially a “cult classic.” Horror aficionados love it. So I watched it over halloween weekend to see what the fuss was about.

Trick ‘r Treat, written and directed by Michael Dougherty, is an anthology film, its intro plus four main stories taking place on halloween night, with characters overlapping in small ways through each of the vignettes. You know, like in Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue from ’88 (that’s right, I’m keeping this essay classy).

On the plus side, it’s a real movie. No cheapo “found footage” crap here. Rich colors. Nice lighting. Well shot. It’s set in a town that celebrates halloween like no place you’ve ever seen, complete with demonic marching band and a downtown packed with costumed celebrants.

It’s got some creepy scenes and images, some surprises, and an evil little halloween demon named Sam, kid-sized with a round burlap sack head. Like maybe he’s a pumpkin with a mask on. He’s genuinely creepy. It’s horrific and bloody in places, but not overly so.

And yet, somehow, I just didn’t get this movie. It’s got all the trappings of a good horror flick, yet it’s missing a key element. What it is is this: the movie is missing a sense of irony to the fates of its characters. But before I get into irony, a word on morality.

Horror is all about morality. If you do something wrong, something you know is evil, it’s going to come back to you. Horror plays on the primal fear we all have of exactly that: should we do something morally questionable, we’ll pay for it, one way or another, and we will deserve exactly what we get. This is how the grim EC Comics stories worked, and it’s what Creepshow faithfully recreates. Most good horror has to do with reaping what you sow.

Camp counselors, too busy screwing, let a boy drown, so his mother comes to camp and hacks them all to pieces in Friday The 13th (Jason, the hockey-masked dead boy all grown up and re-animated, doesn’t appear, as surely you recall, until part 2). Parents murder a child-killer, who comes back in their own childrens’ dreams and murders them in A Nightmare On Elm Street. A scientist invents a serum to re-animate dead bodies, and dies at the hands of his creation in Re-Animator, and for that matter, more or less, in Frankenstein.

Horror is also about making moral decisions. Is it reasonable to live as does Dracula? Killing innocents that you may never die? In An American Werewolf, David, once bitten, will kill every full moon. Should he commit suicide? In The Thing, if the alien reaches civilization, it will be the end of humanity. Should the scientists kill themselves to destroy it?

Creepshow works this conceit perfectly. Even in its simplest stories, there’s a satisfaction to how death is meted out. Leslie Nielson murders his cheating wife and her lover by burying them up to their necks in a beach. The tide comes in and drowns them. But hark! They return as seaweed-strewn zombies—and do the same thing to him! Nothing deep or complicated, but it feels right. In the final story, an asshole clean-freak is eaten from the inside out by marauding cockroaches. Does he deserve it? Hard to say, but it feels like the way he has to go. It’s the sort of ironic death we want from horror.

In the best Creepshow segment, and, I would contend, one of the best (albeit short) horror movies ever made, “The Crate”, it’s not the killer who dies, it’s his horrible wife. She’s the one who deserves a ghastly fate, and it’s she who gets it. It’s scary, over-the-top, gruesome, and deliciously satisfying.

These characters aren’t complex; it’s an anthology; there’s no time for depth. But they’re sketched in a way that brings out the single characteristic required to make their fates feel deserved.

Trick ‘r Treat exists in this world. It mimics the comic book credits of Creepshow. It’s very much a throwback to the anthology movies and series of the ’80s. Some of its evil characters meet evil fates. But their fates lack any sense of irony. There is nothing satisfying about their deaths.

In the intro, a couple returns home from the festivities. The woman hates halloween. She blows out their pumpkin’s candle, despite her boyfriend’s warning: it’s against the rules. He goes inside, she’s killed by the burlap sack boy, Sam. Which means what, exactly? Because she broke a “rule” she has to die? Well, sure. I expected a return to that story at the end, in the classic wraparound of such films, but that’s it. The end.

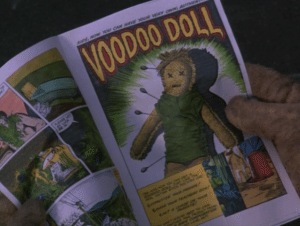

Compare that to Creepshow. On a stormy night, a kids reads a horror comic. His rotten, abusive father throws it out, furious. The comic blows away, and in its flipping pages the rest of the movie plays out. On one page, the order form for a Voodoo doll has been cut out. At the end of the movie, the kid stabs pins into his Voodoo doll, and his father howls in agony. Simple, obvious, and highly satisfying.

Next up in Trick ‘r Trick, a slobby kid kicks over pumpkins and steals candy from the porch of nice guy principal Steven Wilkins (Dylan Baker). Wilkins chats with the kid, only guess what? The candy was poisoned! Wilkins buries the kid’s body out back with still other victims, then carves up the kid’s severed head—with his own young son gleefully helping!

Gruesome and kind of weird. But how, exactly, is this a story? Well, later on, a masked man with vampire teeth kills a woman in the midst of the partying. A seeming one-off. But in another story, a gaggle of slutty girls pick up guys for a party in the woods. One girl is a virgin, and wants, finally, to get laid. But on her way into the woods, she’s attacked by the vampire guy! Yikes!

Cut to the party, and it’s vampire guy who’s all bloody and scared and tied up. And all the other party guys? They’re dead, because the girls are really werewolves. They shed their human skins gruesomely, turn into wolves, and eat their victims. As for vampire guy, it’s Steven Wilkins. He’s horrified as the “virgin” girl eats him, her first kill, you see.

Nice that this nasty fellow winds up dead, but what does being eaten by a werewolf have to with burying kids in your yard?

In another story, some teens go to the old abandoned rock quarry (another nod to Creepshow), where a girl relates the story of how thirty years ago, a bus driver was paid by parents to drive their retarded kids into the quarry. Which flashback is excellent. The kids have seriously disturbing masks on and it’s all shot with an overlit yellowy eerieness. The kids drown, the bus driver is never heard from again.

Well, they go down there, and it seems like they’re all killed by the zombie bus kids, and there’s this one girl left, some kind of savant or something, and she runs for her life and hits her head. But wait, it was a joke by the other kids to scare her. Only then the zombie bus kids really do awaken and kill all the joking kids, with the savant not bothering to save them.

So that’s like almost kind of ironic? I guess? Only why is it so bad that they scared this one girl? Because she’s simple? I don’t know. Maybe if we’d seen the cool kids mistreat the girl at some earlier point? It’s like the story is mimicking the notion of a derserved turn-around without earning it.

Finally there’s this old man who scares kids from his door instead of handing out candy, and the burlap boy, Sam, attacks him. There’s a fight, Sam is unmasked. He’s got a half pumpkin, half demon face, and can’t be killed. He tries to stab the old man, but hits a candy bar instead. Having received a treat, he leaves. And then the busload of zombie kids comes to the door! Because the old man was the bus driver!

Which, again, it’s almost like an ironic death, without actually being one. You feel like you’re supposed to be satisfied, but you are not satisfied. It’s like director Dougherty gets that if you do a bad thing, a bad thing will happen to you, but he forgets to have the two bad things relate, the key element to this equation.

That’s where Trick ‘r Treat goes astray. It apes Creepshow without understanding what it’s aping. It thinks a twist is all it needs to work. But a twist requires set-up for the pay-off to work. Take the werewolf girls. Sexy girls go to a party, you assume to get laid. You figure something nasty will happen to them. Instead, they’re monsters, and they kill some guys. It’s not a story, it’s not ironic, it’s, well, what?

Horror anthologies aren’t required to play out in one way only. In a Twilight Zone kind of a story there needn’t be any irony or just deserts. “Terror At 20,000 Feet” has nothing ironic about it. It’s simply terrifying. But it’s also a story with a beginning, middle, and end.

Trick ‘r Treat doesn’t tell those kind of stories. From the start it’s set up to exist in the kind of horror world that Creepshow does, then fails to fulfill its promises. Compared to today’s typical horror, Trick ‘r Treat has a lot going for it. But I sure hope Dougherty digs a little deeper for his sequel, and brings out the sinister irony he obviously loved in Creepshow

Mind you, Creepshow isn’t the height of movie genius, but it knows exactly what it is. It sets out to tell complete, albeit brief, stories, with gleeful, satisfying comeuppances. And so it does. Plus it’s got a monster in a box, zombies, a killer meterorite, and thousands of deadly bugs. Not a bad deal.