Movie history is littered with bombs turned into classics. Time and word of mouth is what saves these movies from obscurity, if they’re saved at all. These are movies misunderstood upon release, or ignored, or hated by critics, movies you find yourself “knowing” to be terrible without ever having seen them, movies often judged to be bombs before they ever open, even by the studios who produced them, who, opting not to properly advertise movies sure to fail, ensure their failure.

Because of this, I have no doubt you will find it outrageous when I tell you that The Lone Ranger, Disney’s mega-budget, so-called mega-flop of the year, is one of these movies. But it is. The Lone Ranger is one of the best movies of the year, but because of how it was perceived prior to its opening, and, unbelievably, how it was perceived even by people who liked it, nobody bothered to see it. Take Quentin Tarantino, who, much to the surprise of the hip movie crowd, called The Lone Ranger one of his favorites of 2013, yet when he was asked to compare it to his own 2013 western, Django Unchained, dismissed at as unimportant compared to his film, which was “about America.”

The Lone Ranger is about America. It is about Manifest Destiny. It is about American Indians decimated by the government. It is, in short, a giant FUCK YOU to the United States of America. Which explains in part why it was not exactly beloved by those “few” who saw it (in quotes because it made $90 million in the U.S.A., which accounts for more than a few viewers). The other reasons it was not beloved are buried deeper. We’re going to have to do some digging to explain why a movie this good, and this peculiar, holds a dismal rating of 31% on Rotten Tomatoes.

First we go back to 1997 and a very different movie, one loathed almost, but not quite, as much as The Lone Ranger, Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers. When Starship Troopers opened, it resembled all of the other huge, loud, action/sci-fi movies of the era, but was, in every way, “more.” More violent, more outrageous, bigger, louder, and, seemingly, dumber. That it also seemed to possess a certain amount of satire—but not enough! And not the right kind!—only made critics hate it more, too.

I was one of them. When I saw it on opening weekend, all I saw was an abrasive, violent, dumb piece of crap. It gave me a headache. I feared for the future of humanity if this was where movies were headed. Six months later a roommate rented it. I sat down to check out a bit, and within five minutes realized I was watching the best war satire since Dr. Strangelove. How did people miss it? And go on missing it?

I think because the movie hits too close to home. To see the satire of Starship Troopers, which by the way is anything but subtle, is to see that your every favorite special effects action movie is a lovesong to the ideals of fascism. Not exactly what audiences want to be reminded of. All of its action sequences, all the heroics of its characters, are indistinguishable from any other action movie, except in their intensity and outrageousness. This makes it easier to imagine you’re watching something meant to be taken at face value, that the movie is in some way saying, “Sure, these people are acting fascistically, but how else to rid the universe of the evil bug-monsters? These are heroes acting heroically!”

You know something’s up when insane filmmaker Alajandro Jodorowsky, of El Topo and The Holy Mountain fame, says, “But in terms of industrial pictures, there is a picture that I think is a masterwork, and that is Starship Troopers. That, for me, is the most beautiful cowboy picture I have ever seen. It’s fantastic.” This in the same interview where he says, “I think Spielberg is the son from when Walt Disney fucked Minnie Mouse.” Not exactly a fan of the American blockbuster industry.

Starship Troopers is a wonderfully subversive movie, using the form of the sci-fi action flick to make apparent the fascistic nature of sci-fi action flicks, and the ease with which the fascistic mindset can appear normal, can appear to be the appropriate response to a perceived threat. Fortunately, as time has passed, more and more people have realized what’s really going on in Verhoeven’s comedy of war.

What’s really going on in The Lone Ranger is something similar. It too is subversive, using the form of a special effects-laden summer blockbuster, by the makers of the Pirates of The Caribbean series—and produced by Walt Disney Studios, no less!—to take down the past and ongoing policies of the U.S. government.

The weirdest part is that The Lone Ranger does this in the form of a semi-surrealistic, farcical fantasy.

I take that back. The weirdest part of The Lone Ranger is that it’s essentially a remake of Jim Jarmusch’s western masterpiece, Dead Man.

You read that correctly. Dead Man, a low-budget art film in the form of a poem. I wrote about it lovingly a few months ago here. It’s about William Blake (Johnny Depp), a dead man as the film begins, traveling to hell, and further still, on his journey out of this life and into whatever comes after. It is through a western American landscape devastated by “progress” that he travels, led by an American Indian, Nobody (Gary Farmer). Dead Man, too, is a critique of Manifest Destiny and the mistreatment of Native Americans, and it too is part of a long line of revisionist westerns that began in the ‘60s, movies that questioned the glorified heroics portrayed in westerns of the past. It too was a huge bomb at the box office.

In The Lone Ranger, a government lawyer named John Reid (Armie Hammer, way better than you ever dreamed possible from the trailers), is killed in cold blood along with six other Texas Rangers. A spirit horse chooses him to be resurrected. Tonto (Johnny Depp) accomplishes this, gives Reid a mask, and leads him on a spiritual quest to pursue real justice, not the kind espoused by those in power. A railroad tycoon, Latham Cole (Tom Wilkinson), wants to wipe out the Comanche to finish the trans-continental railroad, and sends his vile henchman, Butch Cavendish (a completely awesome William Fichtner), to take care of this so-called lone ranger.

In Dead Man, a captain of industry sends his henchman, named Cole, after the murderous William Blake. Cole is a cannibal, and eats human flesh in one scene. Likewise, Cavendish is a cannibal. After gunning down the Texas Rangers, he cuts out and eats the heart of one of them. He eats his heart. In a Disney movie.

In Dead Man, Depp plays the dead man. In The Lone Ranger, he plays the dead man’s spiritual guide. Are you with me here? The Lone Ranger is a $215 million budgeted summer blockbuster remake of a Jarmusch movie. You must grant that this is unusual.

Back to what I said earlier: The Lone Ranger is a fantasy, it is a farce, and it is a revisionist western every much as Once Upon A Time In The West, Unforgiven, and Dead Man. This is also unusual. It’s one of the reasons audiences and critics came away so confused. Has there ever been a farcical revisionist western? I don’t mean a comedy western, like Blazing Saddles. And I don’t mean a comic movie using classic western structure, like Tampopo. I mean a western that comments on both past westerns and America itself, but does so with the total unrealistic goofiness—underlined by the real human emotion and depth—of a Buster Keaton movie? Not that I can think of.

Not only that, but references to westerns of the past abound in here, some which I caught, others I’m sure slid right by me, not being an expert on the western genre pre-’60s. One thing readily evident, the many allusions to the music of Ennio Morricone in the score.

The Lone Ranger opens in 1933 in San Francisco. A kid wanders into a tent to see an old, old Indian, Tonto, as part of a display. He looks stuffed like the buffalo, but comes alive, and tells the kid, who’s dressed as The Lone Ranger, the story of the real Lone Ranger. And we flash back to when Tonto was much younger.

Okay, Tonto’s story is a farcical fantasy, with surrealistic elements. What does that mean? What does a such a movie even look like? That’s the thing. Nobody knows. We haven’t seen this movie yet. It’s forced to function by accretion. By which I mean, the movie is tonally confusing at first, because you can’t know what kind of movie it is until you’ve watched it.

Early on, a train crashes. Tonto and John Reid, standing atop it, are flung off, they hit the ground and roll, and train parts rain down upon them, and they’re not even bruised. And I didn’t like it. I thought, is this a cartoon? Turns out, it isn’t. But it took some time for me to understand that the movie was functioning as a fantasy, that it was using the “fakeness” of such a standard action-sequence for a greater purpose.

Then there’s the character of Tonto. He’s in some ways very serious, but in other ways, in more ways (at first), he’s comical. John Reid is completely comical. He’s introduced by a small, simple sight-gag that’s the funniest thing I’ve seen in ages. The movie had me there. Yet what about Tonto? Am I supposed to take him seriously? Or is the movie purely jokey?

Soon we get the Ranger massacre, but it’s followed by still more wacky scenes. I was enjoying the movie, but felt it was tonally muddled.

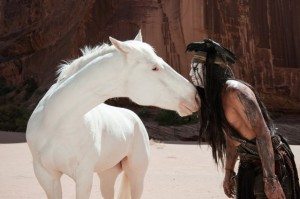

Weirder still, as the Rangers are riding out (soon to be gunned down), they pass a white horse perched on a rocky promontory. What the–? A Ranger explains that the Indians call it a Spirit Horse, but says it like he doesn’t believe such a thing. Well, okay, maybe not—but there’s a white horse prancing on top of a cliff! That’s just—odd.

The massacre happens, and when the baddies have left, Tonto arrives. Only we last saw Tonto in jail.

Cut to the present. The kid caught that too. “How’d you get out of jail?” he asks old Tonto. Tonto gives us a curious look, as though he’s thinking the same thing, i.e. “Yeah, that is weird, isn’t it?” And then we cut back to the movie, and it continues, and you’re with it a moment before thinking, “Hey, wait, he never explained anything!” Only by that point the spirit horse has appeared to select among the fallen Rangers the dopey lawyer, John Reid, much to Tonto’s irritation, and you’re all caught up again.

Strange fantasy moments like these accrue as the movie progresses. And so too do serious moments along with the comedic. Eventually, as Tonto’s devastating backstory is revealed, his character grows deeper. The comedic moments don’t seem glaring. He doesn’t feel tonally inconsistent. It’s just that it takes a while for his character to feel complete. On a second viewing, I suspect that what I found to be troublesome character inconsistencies will seem troublesome no longer.

The same goes for the impossible fantasy elements of the movie. At first they’re jarring, because you have no idea what kind of movie you’re watching. But as weirder and goofier moments keep on coming, you get it, and go with the flow. Tonto claims that nature itself has become unbalanced, hence the unlikely antics of the white horse (e.g. it turns up in a tree and on top of a burning barn), and the rather surprising appearance of demonic bunnies (!) and curious scorpions.

Reid has strange visions. This is where things get surrealistic. By touching certain objects we’re sent into hallucinogenic stream-of-consciousness visions inside his head. This is also not normal in a movie like this. Why does he see what he sees? How can he know what he knows? Because he is dead, I would contend.

Reid’s character is essentially a gullible buffoon, which certainly upset what few old time fans of The Lone Ranger there are. Of course that’s the point of the movie, to tear down notions of western heroism. By the end, Reid is a hero—an outlaw hero. To uphold justice, he has to be.

Meanwhile, the story. As mentioned, the bad guy, Cole, a railroad tycoon, is inciting a Comanche war to wipe them out and finish his railroad, to manifest Manifest Destiny, to spread the U.S. of A. as far as it will go. Summer blockbusters always have these kind of corporate bad guys with their nasty henchmen (it’s technically a spoiler that Cavendish works for him, but not exactly—if you’ve ever seen a movie before, you know what’s going on, and knowing doesn’t detract), but in The Lone Ranger the goal of the bad guy is tied directly in to the message of the movie: that the U.S. government is peopled by liars, thieves, and murderers, and given that state of affairs, the only way to achieve justice is to be an outlaw, to wear a mask.

That’s serious business for a summer effects flick. What better reason to turn it into a Buster Keaton farce?

Keaton’s The General comes to mind most readily in the finale, an insane multiple train chase, one of the best CGI-powered action sequences I’ve ever seen. I saw a screening (in 35mm, no less!) of the movie at the Castro Theatre over the weekend (courtesy of Jesse Hawthorne Ficks’s monthly Midnites For Maniacs* triple bills), with 300 other doubters that this movie could be anything but a turd, and the whole place erupted in applause when this sequence ended. It’s completely absurd and over-the-top, full of sight gags and hilarious impossibilities. It’s played purely as a fantasy, and in doing so it’s just as subversive as Starship Troopers. Better still, it’s scored with Rossini’s “William Tell Overture” (that’s The Lone Ranger theme music of old, for you youngins out there).

Suddenly both western heroics and the typical CGI-enhanced heroics seen in every other summer blockbuster are shown for what they are: fantasy; Buster Keaton style lunacy.

That a summer blockbuster can tie the style of its CGI action sequences to a thematic critique of how the U.S. perceives its actions throughout history is, shall we say, unlikely. And amazing.

I’m not a fan of director Gore Verbinski’s previous movies. I didn’t even like his previous western, the animated Rango, that everyone went nuts for. But by using his regular writers, Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio, and adding Revolutionary Road scribe Justin Haythe, he’s created something completely different than any bloated Hollywood spectacular I’ve ever seen.

No wonder it tanked.

Another difference between The Lone Ranger and typical summer fare is that it poses unanswered questions. Is old Tonto even real? What about this story he tells? Is it the real story? Is the fantasy all in Tonto’s head? What does it mean if it is? What does it mean if it isn’t? How are we supposed to read the logical lapses? The typical movie-goer, and the typical critic, aren’t known to be beloved of movies that don’t make their messages and intentions clear, that ask questions instead of answering them, that ask the viewer to put together what’s shown on screen, that takes a familiar form and renders it–weird.

It’s too bad there’s no way to sell a movie like this. You can’t advertise a unique western-fantasy-historically-critical-surreal-comedy-summer-popcorn movie. So Disney didn’t. They advertised an explodey blockbuster. People went in, stared baffled for two and a half hours, and left confused, bored, and unsatisfied.

I think there’s hope yet for this movie. It may take time, but like Starship Troopers and Dead Man and so many other misunderstood movies of Hollywood past, The Lone Ranger demands future reappraisal. Of course the first step is for smart people—like you!—to see it. I hope you’re so consumed by disbelief at this essay that you’re impelled to rent it and find out for yourself.

*This particular Midnites For Maniacs triple feature ran: The Lone Ranger, Dead Man, and Walker, a ciminally overlooked ’87 film by Repo Man director Alex Cox. You are advised to watch all three in exactly this order. And if in the Bay Area to attend future M4M screenings.

This is definitely contrary to conventional wisdom–when you gave me this argument in person on Saturday I thought it was wild. I’m so curious to see it.

I am so consumed by disbelief at this essay that I feel impelled to rent it and find out for myself.

Really, I’m stunned. I’ll definitely watch it when it shows up on the cable.

This is all I could ask. I saw it on a genius triple bill followed by Dead Man and the forgotten Alex Cox film Walker. Which you should also watch.

But yeah. The Lone Ranger. I was stunned.

I’m sorry I missed it now.

If the movie is 1/4 as entertaining as your review it will be a worthwhile watch. Awesome write-up, mate!

Thanks. I’m still waiting for someone who saw it and hated it to tell me I’m insane, and why.

You’ll be waiting a long time. I know exactly two people who saw it: my mother and my father — an old-school Lone Ranger fan.

They enjoyed it at face value.

I loved it.

Worth listening to the review on the Film Talk podcast. They came to the same conclusions as you.

Good to know.

Lone Ranger queued up for tonight. And, as luck would have it, Walker is currently on Netflix streaming.

I’ll keep my fingers crossed that you don’t think I’m delusional.

I have now watched The Lone Ranger.

On the one hand: I liked it a lot more than I would have expected before I read your post. On the other… I think the aspirations you see in it are a far cry from Starship Troopers and Dead Man.

There are moments, undercurrents of subversive innuendo, that lead to some wry commentary. And I like it. But it isn’t cohesive or comprehensible in a way those other films are, where you flip a mental switch and everything fits together in psychic harmony. And so much of the film is not in service to these goals — in Starship Troopers, the whole film is in on the joke. In The Lone Ranger, most of the film is unaware. There are long sequences and whole plots that have nothing at all to do with Manifest Destiny, or anything else — such as everything with Helena Bonham Carter.

So it’s like Verbinski snuck his subversive message into a giant, bloated blockbuster, not that he cleverly disguised something subversive as a giant, bloated blockbuster. There’s a big difference.

There’s meat to the Lone Ranger but it isn’t a full meal. It left me hungry.

I dug the killer bunnies and the magical horse and the Lone Ranger being naive. I liked the surreality/fantasy of Tonto’s conversation/story. I also appreciate how the format of this film brings other films, ones you’ve grown up with and accepted, into question. (Particularly his nod to Peckinpah, with the transvestite thief marching around singing Shall We Gather at the River). There were lots of moments like that, as there were in Rango, which I liked better than you.

And it worked better than Rango in many ways, but Rango felt like one exceptionally weird and mostly ill-judged and yet compelling film. This felt like a few different films that never quite got acquainted. I don’t know that it worked, completely, on any level.

For it to be the film you want it to be, Ruth Wilson’s widow character would have had to be something other than what she appears on the surface; and she isn’t. There’s nothing to that role. She buys a scarf. That’s her big business. Was there something about the boy really being John’s? I wanted there to be, but I didn’t see it. John hadn’t fired a gun in nine years since…. what? Never explained. Is it all because he’s dead? That just doesn’t mean anything to me in the context of this picture. If he’s dead: what is Verbinski saying with that? Only a dead man can stop Manifest Destiny? In Dead Man, William Blake’s denial of his mortality is the crux of the whole story. Here, I’m not sure much would need to change if John never got shot at all (except they’d be straying from the original Lone Ranger story).

I would also say the film seems to be more anti-corporate than anti-American/governmental. The soldiers are unwitting pawns of the railroad. Laws are corrupted by money. It isn’t the US of A that’s made nature out of balance, it’s greed. And greed continues whether you believe Tonto’s tale or not.

But a Disney blockbuster that’s anti-greed? Strange days indeed. Welcome ones, but strange.

So I enjoyed The Lone Ranger. I think people should see it, particularly people like me who enjoy some blockbuster spectacle and want something to think about, too. I’m not sure it’ll make my best of list, though. It’s amazing for what it is and for what I expected it to be. More than that I’ll have to sleep on.

The danger in writing such an essay is having moved expectations too far in the opposite direction.

So, yes. It’s not Starship Troopers, where the very form of the movie is part of the subversive message. It’s a blockbuster with more than usual going on within it. And though it mimics the characters and in some ways the story of Dead Man, it’s not recreating the actual meaning of Dead Man. It’s got different matters on its mind.

But so anyway. Glad you gave it a shot.

As am I. I never would have seen it otherwise.

After a night’s sleep I think the key to the film is the Chief’s statement that ‘we are already dead, so it does not matter’ or whatever it is he says exactly. I’m just not sure how that plays out in John’s actions. Perhaps, the film is suggesting it is only by accepting our defeat that we will find the courage to fight the impossible battles.

I’m also toying with the idea that John died ‘nine years ago’, and his pursuit of justice through law is his fatal flaw. This kind of works. It explains why he can’t be killed and why he can’t stay with the widow Ruth and why Tonto doesn’t bother fighting him even when he should. It’s an extra-legal ghost story encouraging revolutionary terrorism?

I like it! As in Dead Man, John is introduced riding in a train.

Also of interest, in terms of the end, old Tonto dresses in a suit and hat, and vanishes. Pretty obvious symbolism there. The story he tells is clearly a fantasy. It can’t have happened that way. The Lone Ranger may have fought on, but as you say, it was an impossible battle. But he’s telling the kid that he has to wear the mask and fight regardless.

Yeah. There’s something to pick apart there. John appears in a train filled with religious zealots (or protestants, i can’t recall). Won’t you pray, they ask? My bible is right here: the rule of government. He is in the false heaven of authority.

I also like that Tonto’s diorama has no glass; you see him sort of check that he’s able to move through it (maybe?). i.e. this way that the world was isn’t so removed from what we can have today. Kids can interact and be part of older, more sensible, less ‘out of balance’ ways.

I just wish I had been as moved by the action scenes as you were. Seeing them on the tv was doubtlessly less engaging. Still; I continue to think about Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger and I never thought I’d utter that sentence.

This doesn’t mean I have to watch Pirates of the Caribbean 3 does it?

The opening action scene, as I mention in the piece, didn’t do it for me. But once I accepted that I was watching a fantasy, the later ones really clicked for me in a way these things rarely do. Because for once a movie like this didn’t ask me to accept what was happening as real, and then pushed the absurdity over the top. Or something like that. And yeah, seeing it at the Castro surely helped.

I saw Pirates 1. That felt like more than enough. I leave the sequels to you.

I abashedly enjoy Pirates 1, or did the last time I watched it. Chapters 2 & 3 have some fun effects (Bill Nighy as a the pirate Cthulhu works) but the stories are evisceratingly terrible. I think there was a 4th one? That I’ll miss.

Will there be a Lone Ranger 2, I wonder? Alas, probably not.

There’s four of them? I had no idea. I see number 4 was not directed by Verbinski. And there’s a 5th one announced! Sweet jeebus. It’s being directed by the guys who made Kon-Tiki. I guess because that was also about a boat?

Pirates 1 is good, clean fun. Pirates 2 and 3 are pretty weak. 4 is just abysmal. No one has any reason to do anything, and there’s just no life in it. It’s one of those movies where everyone just wanders around, presumably looking for their paycheck.