Norman Jewison isn’t one of those directors whose name sets off a flurry of flashbulbs. He never won an Academy Award, or played golf with Richard Nixon (I’m assuming), or saved Paris with a super magnet and a ten-pound bag of smelt, like some others I won’t mention.

He is, however, the man behind more than a few intriguing films, some of which you might enjoy this holiday season. Without him we’d have no one-handed Nic Cage in Moonstruck, no schtick in Fiddler on the Roof, no Rollerballing James Caan, and no In the Heat of the Night. We’d also be unlikely to recognize names such as Hal Ashby, Alan Arkin, Lalo Schiffrin, and Denzel Washington. The Academy nominated Jewison for directing five different films but so far he’s had to settle for an Irving Thalberg honorary award and five-pound bag of smelt.

He is, however, the man behind more than a few intriguing films, some of which you might enjoy this holiday season. Without him we’d have no one-handed Nic Cage in Moonstruck, no schtick in Fiddler on the Roof, no Rollerballing James Caan, and no In the Heat of the Night. We’d also be unlikely to recognize names such as Hal Ashby, Alan Arkin, Lalo Schiffrin, and Denzel Washington. The Academy nominated Jewison for directing five different films but so far he’s had to settle for an Irving Thalberg honorary award and five-pound bag of smelt.

I guess everyone’s too busy giving statues to Argo and American Hustle to remember hard-working, socially conscious, upstanding and interesting Norman.

Jewison, a Canadian (and not Jewish, despite the name and Fiddler), progressed from directing television musical revues in the 1950s, to light Doris Day / Rock Hudson comedies, to damn fine films in the late ’60s and beyond. It was Norman Jewison who swiped young proto-editor Hal Ashby from William Wyler and gave him his first real chance behind the splicer. Together the pair made a run of films together: The Cincinnati Kid, The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming, In the Heat of the Night, and The Thomas Crown Affair.

Then Jewison set Ashby up directing what would be the younger man’s first feature—The Landlord—and the pair did more damage working apart.

But as much as I adore Ashby’s films, I’d never really taken a good look at the work of his mentor. I hadn’t watched most of these Norman Jewison films until this month.

The Cincinnati Kid (1965)

The Cincinnati Kid was Jewison’s first stab at a dramatic feature after being pigeonholed as a comedy director. It’s Steve McQueen and his ice blue eyes facing off across a poker table with Edward G. Robinson’s older, wiser, man-to-beat. If that synopsis reminds you of Paul Newman’s ice blue eyes facing off across the felt with older, wiser, Jackie Gleason in The Hustler, you aren’t the only one.

This film’s different however. It’s in color. Hearts and clubs were too hard to distinguish from each other in monochrome (as Sam Peckinpah planned on shooting it, until he got fired off the picture).

While comparisons to The Hustler are inevitable and generally unflattering to The Cincinnati Kid, this film isn’t a rip off or a retread. There is something wilder and dirtier happening here, particularly when Ann Margret’s untamed sex kitten starts slinking around. You also get Karl Malden and Rip Torn and Tuesday Weld and even Cab Calloway inhabiting the shadows of 1930s New Orleans.

While comparisons to The Hustler are inevitable and generally unflattering to The Cincinnati Kid, this film isn’t a rip off or a retread. There is something wilder and dirtier happening here, particularly when Ann Margret’s untamed sex kitten starts slinking around. You also get Karl Malden and Rip Torn and Tuesday Weld and even Cab Calloway inhabiting the shadows of 1930s New Orleans.

The Cincinnati Kid essentially pushes its luck, though, and that describes both the story and the experience of watching it. McQueen displays casual swagger in his period costumes, but his character is so indefatigable you know he’ll have to lose. Perhaps you can hang that on Jewison’s Canadian-style slant on American over confidence?

Touché Norman, touché.

Rip Torn—looking like the Platonic ideal from which Seth Rogan was cast—does some good slithering, and there’s a cockfight you might be interested in as well. I bet you hear that all the time, though. Karl Malden’s had better parts and done more in them.

Come for the poker, stay for Ann Margret, and don’t forget to tip your waitress.

The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966)

I’m warning you right now: The Russians Are Coming has the most irritating title sequence of all time. Its flippy-floppy Soviet and American flag graphics were the newest hippest thing in 1966, but today they’re like a particularly infuriating MySpace page.

Luckily, once you get past the credits, The Russians Are Coming gets significantly more enjoyable.

In brief, what you’ve got here is a parable about Cold War hysteria. A Soviet submarine runs aground on an East Coast island, forcing the flummoxed sailors to impose on the panicked islanders in order to effect an escape. Carl Reiner plays the dad who first gets entangled with the unfortunate invaders, Eva Marie Saint is his underused wife, and Alan Arkin—in his first significant screen role—leads the landing party. (He actually spoke Russian.)

In brief, what you’ve got here is a parable about Cold War hysteria. A Soviet submarine runs aground on an East Coast island, forcing the flummoxed sailors to impose on the panicked islanders in order to effect an escape. Carl Reiner plays the dad who first gets entangled with the unfortunate invaders, Eva Marie Saint is his underused wife, and Alan Arkin—in his first significant screen role—leads the landing party. (He actually spoke Russian.)

The rest of the town is drunk, armed, and hysterical, convinced the Soviets are staging a full-scale invasion of their sleepy speck of vacation real estate.

On the plus side, The Russians Are Coming taps some of that It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World chaotic energy, particularly when the beleaguered Police Chief (Brian Keith) attempts to keep order. On the down side, the ending is about as unforced as the Patriot Act.

Jewison blows some fresh air into closed jingoistic minds with this comedy, but it’s comedy, and mostly slapstick at that. I bet the John Birch Society hated it.

I liked Alan Arkin and could have done without most of the rest, including the cute babysitter who falls for the hunky Soviet sailor.

In the Heat of the Night (1967)

And then Norman Jewison got funding to make something serious, In the Heat of the Night. The subject matter—civil rights—had been on his mind since he’d hitched around the American South as soldier on leave.

You’re smarter than any white man. You’re just gonna stay here and show us all. You’ve got such a big head that you could never live with yourself unless you could put us all to shame. You wanna know something, Virgil? I don’t think that you could let an opportunity like that pass by.

In the film, Sidney Poitier plays Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia policeman caught up in a small town Southern murder case. Poitier, you may have noticed, is African-American. The local police chief—and everyone else in Sparta who can sit at the lunch counter—isn’t. Rod Steiger brilliantly plays the chief and Warren Oates gets in a good turn as his thick-skulled deputy. All of them are well-rounded characters, not easy caricatures.

Rewatching In The Heat of the Night, it’s more than the film’s perfect timing that made it a giant killer and Best Picture of 1967. This sweat box strands you in the dusty, bigoted backwater of Sparta beside Virgil, regardless of your skin tone. And it’s not about how racism is wrong; it’s about how empathy and understanding is right. At the film’s core, we’re circling with Virgil Tibbs and Steiger’s Chief Gillespie, trying to paw past assumptions to something resembling solid ground.

There are fantastic sequences in Heat of the Night, for which Ashby won Best Editor. Most of these involve the overheated world of Sparta colliding with the always cool Virgil Tibbs. Watch him simmer, but see him hold, even when he’s taking and returning a slap across the face.

There are fantastic sequences in Heat of the Night, for which Ashby won Best Editor. Most of these involve the overheated world of Sparta colliding with the always cool Virgil Tibbs. Watch him simmer, but see him hold, even when he’s taking and returning a slap across the face.

Who killed Sparta’s industrial tycoon may be the mystery that drives the plot, but the real question is if there’s room for any real revelations in this America. Are we ready to face the truth, even if it’s not what we’d want or expect?

Ya’ll take care now, y’hear?

The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

Hal Ashby fans will be familiar with The Thomas Crown Affair. In Ashby’s masterpiece Being There, a famous scene involves one of the oddest seductions in film history; Chauncy Gardener (Peter Sellers) inspires Eve Rand (Shirley MacLaine) to passion using only a television set.

It is the suggestive game of chess from The Thomas Crown Affair, in which Faye Dunaway seems to best Steve McQueen with her feminine wiles, which plays on the TV Sellers watches.

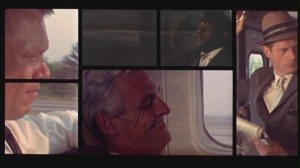

Trivia aside, the original Thomas Crown Affair—and not the remake with Pierce Brosnan and Rene Russo—is a stylish caper film with a lot going for it. This is the film in which split screen, multi-dynamic editing first appeared before a mass audience. This technique let Jewison unspool the separate strands of his heist simultaneously, as McQueen’s Thomas Crown plays puppet master. It’s also a film that gives Faye Dunaway the sort of room to move she deserves.

Plot-wise, it’s the story of a super-rich businessman who robs banks to see if he can. Turns out: he can. Unless Faye Dunaway’s insurance investigator, Vicki Anderson, can catch him.

Plot-wise, it’s the story of a super-rich businessman who robs banks to see if he can. Turns out: he can. Unless Faye Dunaway’s insurance investigator, Vicki Anderson, can catch him.

It sounds like standard fare, but it isn’t. This is no case of cat and mouse. It’s a match between venus flytraps. Sticky-sweet honey pots with lots of easy cash and only enough morality to understand there theirs are lacking.

The Thomas Crown Affair is no In the Heat of the Night. All the same, I’ll let you discover which leaves you more hot and bothered.