Women, right? Can’t live with ’em—so they say—unless you’re lucky, or you are one, or you live with, I dunno, a mother who loves you or something.

You do have a mother, right? Good. Then we’re in agreement. Women are the only thing standing between us and the void of despair.

But things aren’t exactly tip-top for females film-wise. Women have been getting short shrift at the cinema since there have been cinemas. And as much as I appreciate a short shrift, this is what we professionals call a fine how-do.

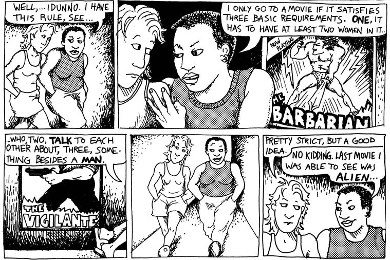

Recently, theaters in Sweden made inter-news on this topic by posting how well the films they’re screening fare against the Bechdel Test. The Bechdel Test sprang from a comic called Dykes to Watch Out For by Alison Bechdel way back in 1985. It’s pretty simple. It asks three questions of any film:

- Does it have at least two women in it;

- Who talk to each other;

- About something besides a man?

It wasn’t meant as a serious metric, but rather as a way to help us come to terms with just how lacking the portrayal of women is in film in general. If this is the first you’re hearing of the Bechdel Test, you might be amazed at just how few films pass it—even without the more recent adjustment that requires the two conversing women to have names.

Films as popular and varied as Gravity, Avatar, all three original Star Wars films, all eleventy-one hours of the Lord of the Rings, and even Run, Lola, Run — which is the story of a woman — fail the Bechdel Test. By a disturbingly wide margin, most films fail.

If you haven’t noticed this on your ownsome, you may be male. Please check now.

Of course, some films that you wouldn’t think would pass, pass. Evil Dead, in which one of the female characters gets raped by a tree aces the Bechdel Test. So does everyone’s favorite feminist tract, Zack Snyder’s Sucker Punch. This just serves to illustrate that the test isn’t a scorecard, as the well-intentioned Swedes are using it to be. It was just something a character in a comic strip said to illustrate a real problem, and which subsequently took on a life of its own. The Bechdel Test should make you realize just how pathetic Hollywood is when it comes to treating female characters like full-fledged cinematic citizens.

Does that ubiquitous sexism make you feel testy? Are you filled with Bechdel testiness? Good. Let us harness your righteous rage while we watch two films that demonstrate exactly how fakakta things are for females in film.

The Women (1939)

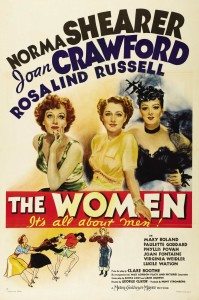

Oh lordy was it a big to-do. Way back in 1939, (year of Gunga Din and others) George Cukor turned Clare Boothe Luce’s play The Women into a film. The script was written by two women (Anita Loos and Jane Murfin) and starred a whole passel of women.

Oh lordy was it a big to-do. Way back in 1939, (year of Gunga Din and others) George Cukor turned Clare Boothe Luce’s play The Women into a film. The script was written by two women (Anita Loos and Jane Murfin) and starred a whole passel of women.

In fact, there is not a single male face in the entire picture. Every single actor is female, even the pets and the people in the paintings.

So hooray! Why can’t we make movies this pro-female today? That’s a trick question, sucker. Because despite being all about the lives of women and featuring everyone from Joan Crawford to Rosalind Russell to Butterfly Goddamned McQueen, this film doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test.

sssscrrriiiitttccCCHHHH WHAT?!?!?

Yep. The Women, a totally fascinating piece of history that’s most definitely worth watching, doesn’t feature any significant dialogue in which any of the women—ANY OF THE WOMEN—talk about something other than men for more than a passing moment. The entire picture is a morass of gossip, infidelity, fashion, divorce, society, and cosmetics. Look at the stinkin’ poster, fer crissakes. It says it right there under the title:

It’s all about men!

As if, you know, that’s what women want to see at the moving picture show.

Luckily, we’ve learned a lot about how women should be respectfully portrayed since 1939. There have been a number of remakes of The Women—one in 1956 called The Opposite of Sex; one in 1977 by German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, called The Women of New York; and one as recently as 2008, directed by Murphy Brown creator Diane English and starring Meg Ryan, Jada Pinkett Smith, Eva Mendes, etc. etc. All of those films took a large step away from depicting women as gossiping, male-focused, society-snob, flibbertigibbets.

What? They all tell pretty much exactly the same story?

Damn. That’s cold.

And totally predictable.

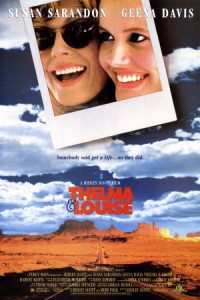

Thelma & Louise (1991)

The other day we were taking a hard look at the career of Ridley Scott. He made Alien and Blade Runner—both absolutely brilliant films (and Alien the film mentioned as an example in the original Bechdel Test comic above)—and then…

Not so much worth seeing.

Looking at Ridley Scott’s credits is depressing. There are a ton of films in there you’d like to love, but almost none you do without feeling tawdry. Legend? Black Hawk Down? Prometheus? If you even mention Gladiator I’m going to have fork you in the eyes. That movie is terrible, even for a Best Picture Oscar winner.

While many of Ridley Scott’s movies have visual style and even more are competently directed, none of them even remotely touches on his earlier brilliance—except for Thelma & Louise. And therein lies the story.

Having just revisited this film, I am quite happy to place it both on the passing side of the Bechdel Test (with flying colors) and in the win column for poor old Ridley. Except for one thing: I wonder if Ridley Scott had any idea he was making a film that women would recognize as important.

Can that be possible? It’s almost inconceivable. After all, Thelma & Louise is the story of how two women—who are literally and figuratively assaulted by men—refuse to succumb ever again.

Hard to believe or not, Ridley either directed Thelma & Louise exactly as he’d make any other male-dominated picture, or he did so ironically. You watch this tale of women who refuse to be cornered and you be the judge.

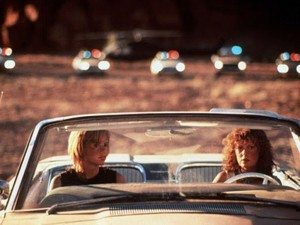

In his DVD commentary—speaking about the ending, one of the most discussed scenes in feminist film history—Scott goes on about how the ‘girls’ did a great job and looked pretty. Which, sure, they did and do, but I kind of think he’s missing the point. Especially as over the course of the film Susan Sarandon’s Louise deliberately strips herself of ornament and artifice; just as Geena Davis’ Thelma abandons her demure subservience in favor of deliciously unfettered joy.

They look pretty? Clue phone, Ridley. It’s for you.

I’m almost sorry there isn’t a scene in Thelma & Louise in which Ridley Scott calls the girls pretty and then gets duct taped to a windmill.

Throughout Thelma & Louise, the direction is almost oppressively masculine. Some of the overwhelming phallicity (a word I just made up as an alternative to ‘cockiness’) is surely intentional, setting the stage for the drama. Other elements just seem to be “the way films are made” regardless of subject or subtext. This is recognizable in Hans Zimmer’s thudding score and in the girly mag, Top Gun-style cinematography.

Yet Thelma & Louise is a great film. This story of two female friends who run afoul of male society lays the whole problem with women and Hollywood in front of you like a yard and a half of soiled silk. This is thanks to Callie Khouri’s script and the accomplished performances of the leads—not Ridley Scott.

You can imagine Sarandon and Davis’ surprise at finding parts like these in front of them. They are once in a lifetime roles for any actress. You wouldn’t guess it from the trailer, though.

Watch and see if you think this film is going to be anything special:

It looks insipid from that ad, right? Well, it isn’t. I could easily write an entire 2500 word essay on how Thelma & Louise deconstructs the world of men in search of a way out for women—any way out. In the film, the machismo-tainted miasma of society literally makes both women sick. They wonder if they’re to blame, as is normal for any abuse survivor. They bolt between bad options, co-opting men’s ways and rejecting men’s ways, until they find their own solution, as short-lived as that may be.

Watching Thelma & Louise again after many years, I still feel the frisson of seeing something rare and wild, even with Ridley Scott shooting the picture like it was one of his late brother Tony Scott’s—The Last Boy Scout, perhaps?

See, the thing that makes Thelma & Louise stand out is that step by step, these women reject the world of men as built on a package of cheap but effective illusion. Which it is, as clearly evidenced by the filmmakers themselves.

Without spoiling the plot of the film, consider what screenwriter Callie Khouri says about the famous ending:

Women who are completely free from all the shackles that restrain them have no place in this world. The world is not big enough to support them … I loved that ending and I loved the imagery. After all they went through, I didn’t want anybody to be able to touch them.

And listen to the Marianne Faithfull track (written, actually by Shel Silverstein) that anchors the film, The Ballad of Lucy Jordan. Why they didn’t ask Faithfull to score the film instead of Hans Zimmer? I’ll never know. Unless the reason is pervasive sexism, in which case, oh yeah. I just watched two films that reminded me all about how much of that there is.

So I’m guessing “Lawrence of Arabia” didn’t pass the Bechdel Test then?

Nope.