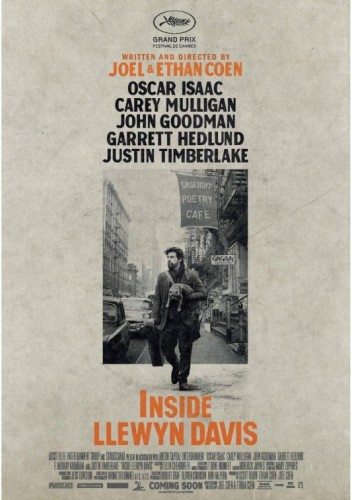

Inside Llewyn Davis, in which Joel and Ethan Coen go dark and plotless for their look at a struggling New York folk singer in ’61, is their best movie since Barton Fink. And I love Barton Fink. It’s better than No Country For Old Men, though nobody dies horribly, at least not in the literal sense. In the soul-crushing sense, maybe someone does.

Oscar Isaac plays Llewyn, a folk singer who’s just put out his first solo album. Nobody’s buying it. Nobody’s heard of it. Llewyn is, mostly, an asshole, yet as played by Isaac, he’s an unusually endearing one. You want to spend time with him. You want him to succeed, at least as much as Llewyn himself wants to succeed, which is actually up in the air, his level of desire. On the face of it, of course he wants success and recognition. But something deeper is going on within him. He refuses to forego his artistic purity–but does he have artistic purity? His songs are soulful and ragged around the edges, a far cry from the shimmering, ethereal beauty of the other folk singers heard in the movie (played by Justin Timberlake, Stark Sands, and Carey Mulligan), but one has the feeling something’s missing.

When Llewyn arrives in Chicago to play for top manager Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham), he plays a rough, beautiful song. It’s the kind of moment where in any other movie Grossman would sign him on the spot. In this movie, things don’t work out so neatly.

I love that Inside Llewyn Davis is about a struggling artist trying to make it—who doesn’t make it. Who just struggles. That’s what the movie is about. The struggle. Which, depending on how you read the ending, might go on forever. I won’t tell you about the ending. It sneaks up on you. It happens when it needs to.

A strong ending is important for a plotless, meandering movie. Also important is not being boring. Inside Llewyn Davis is not boring. It moves with a deliberate, laid-back pace. It’s slow but never dull. It moves along steadily, but never speedily. It just goes. Llewyn plays his songs, argues with Jean (Carey Mulligan), whom he may or may not have impregnated—but it’s okay, he knows a doctor, he knocks up women all the time—loses his university professor friend’s cat, finds a different couch to crash on nightly, and generally antagonizes everyone he encounters.

Llewyn knows he’s a bastard. He knows the world is cold and hard and unlikely to reward him with anything at all. He doesn’t ask for sympathy and he doesn’t expect any. I wish I could relate the brief exchange he has with Grossman in Chicago after he plays his song, but it wouldn’t be fair to ruin it for you. It’s a perfect encapsulation of the movie. It’s Llewyn’s world-weariness and his acceptance of that wearying world in one clarifying moment.

This is a Coen brothers movie, so you know Llewyn’s going to meet some quirky people in his travels. Prime among them are John Goodman as Roland Turner, an old jazzman strung out on heroin who won’t shut up and doesn’t like cats, Garrett Hedlund as a taciturn Kerouac type, and Adam Driver (of Girls fame) as a dopey cowboy singer who records an hilarious novelty song with Llewyn and Jim (Timberlake) about rockets and Kennedy.

These people are all very Coenesque, yet toned down from the oddballs typically inhabiting their movies. Everything about Inside Llewyn Davis feels less consciously odd than usual. Everything is muted. The cinematography, by Bruno Delbonnel (first time working with the Coens), paints scenes in subdued greys and browns, creating a cold, sad atmosphere. Wintertime New York has rarely felt so chilly and oppressive. One scene, during the drive to Chicago, is set in one of those restaurants spanning the highway. It’s bright and shiny, empty and cold, the middle of the night. Llewyn sits with Turner and Johnny Five (Hedland), who recites a poem. Below them, out of focus through the dark windows, headlights stream by in one direction, tail lights in the other.

The world moves on, while Llewyn remains frozen.

Llewyn is so very alone. He’s such a peculiar character to center a movie around. It was a good move to give him a cat. Which in case you’re worried the cat is a cheap way to humanize a bastard of a character, don’t. Things with the cat work out as surprisingly as everything else in the movie.

Mind you, the surprises are of the low-key variety. Everything about Inside Llewyn Davis is low-key. Even the world of folk singers is low-key. I’ve read a lot about the movie’s recreation of the early ‘60s folk scene, but aside from the few characters we meet, and the handful of songs we hear, I don’t know that a “scene” has been recreated. The movie isn’t about the scene. It’s about this one man who’s angrily fighting against it (the scene) as much as he’s fighting to be a part of it. He wants it and he hates it.

I’m finding this movie difficult to write about. I feel like ten years from now, when it’s had time to sit with me and I’ve seen it five or six times, I’ll have more to say. Because everything that happens in here happens below the surface. The surface is lovely too, it’s full of great performances, both acting and musically speaking, but I’ve already described it (the surface) for you. An intense, self-aware, pain-in-the-ass artist struggles to make it. He meets some people. Sings some songs. And, more or less, fails at everything. Why, in the hands of the Coens, this is so interesting, and what it says about art, and loneliness, and self—that’s the beginning of the conversation on what’s simmering underneath.

And that’s as far as I’ve come, one day after seeing it—the beginning of the conversation.

The Coens only make movies about characters down on their luck, but few have been as down as Llewyn. Most of the others, whether or not they ever achieve their dreams, believe they will, however briefly. Some do it all for friendship. Some grow old and raise a family. Some are happy simply bowling. What dream is Llewyn chasing, and does he ever really believe in it? That I don’t know.

I also don’t know how the Coens made a low-key, plotless, meandering and morose movie so heartfelt and fascinating. I’m going to see it again and think on it.

When I first walked out of the theater, I felt like it was a good film but that it didn’t leave me with much.

A day later, I’m ready to see it again and I can’t stop thinking about it.

There’s something there about Llewyn needing to feel the hurt (and don’t read on if you haven’t seen it yet) born of the death of his partner. He seems to actively seek out punishment, self-destructing at every turn, because (I guess) he can’t let the pain in unless it calls him out back and punches him repeatedly in the face. It is only at the end that he can tell Jean he loves her, as his exhaustion erodes his facade. It’s not that he’s an asshole. It’s that he needs people to hate him and reject him.

That’s what I’ve got so far. That Inside Llewyn Davis is the story of man seeking pain. What that has to do with folk music, I’m unsure. Although the setting worked excellently.

Today I’m wondering what Llewyn was like before his partner killed himself.

I’d say he was much the same. Perhaps with more hope and less cynicism.

I think you’re right about the asshole-ish factor. He behaves the way he behaves for the purpose of being rejected, as though to be rejected proves the value of both his art and himself.