Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Or these two.

The first part of this ramble is about a story — original, complex, well-considered — but retold all in a jumble for inexplicable reasons. The second part is about a different story — unoriginal, simple, straightforward — that’s retold with good timing and subtle insight, so as to give meaning a gap to sprout from its corners.

The first is the Extended Edition of The Wolverine and the second is Nebraska. They are both old stories and that’s where the similarity ends.

If you grew up, like me, reading X-Men comic books, then the storyline upon which The Wolverine is based will be familiar. An animalistic killer struggling with his identity heads to Japan to save the refined woman he loves — the scion of a massive business empire. There he gets confronted with super villains and ninja and evil doers of other stripes. He must master the wild within himself and prove his honor in a society that treasures it above all else.

If you grew up, like me, reading X-Men comic books, then the storyline upon which The Wolverine is based will be familiar. An animalistic killer struggling with his identity heads to Japan to save the refined woman he loves — the scion of a massive business empire. There he gets confronted with super villains and ninja and evil doers of other stripes. He must master the wild within himself and prove his honor in a society that treasures it above all else.

It is a Shakespearean tale and a tragic one. While it may be comic book bold, its violence is rooted in the characters’ internal struggles. Its drama and its resolutions are far from juvenile.

But you’d barely get any of that if you watched The Wolverine. It is almost as if the filmmakers started the film with a title card reading:

This film is based on actual comic books but all names and personalities and situations have been changed to protect the shareholders from evincing the slightest bit of faith in their audience.

Yep. That’s happening because, uh, her name is Viper and if she didn’t peel her skin off you might forget that she’s snaky.

In the wispiest possible way, James Mangold’s The Wolverine traipses along the major plot points of the original story. When plot points require emotional investment on behalf of the viewer, they’re replaced with bloodless action scenes or rewritten to allow some preposterous character to shed her skin like a snake or, in another example, to allow a different character to completely reverse his personality in a denouement that’s only surprising if you can’t count.

The ultimate effect is like having your mom read you your favorite bedtime story, but from memory while listening to three different television channels simultaneously. Bits and pieces from all over muscle their way into this chaotic retelling of the familiar tale. While you at first raise an eyebrow at the diversions and discrepancies, eventually you just wonder what they hell is going on and why.

It’s like: “Let’s do King Lear, but instead of three daughters, let’s give the old king venom breath and an expertise in biochemistry. That’s more or less the same thing, right? Explaining all those daughters would be boring and they won’t make for good action scenes.”

Not that the Wolverine comics were King Lear, but you get what I’m saying. You can’t strip mine a story for salable points and abandon the context and motivation without ending up with an industrial ruin. Which is what this film is.

Instead of mysterious love — that illustrative confluence of the animal and the human — here we get an instantaneous romance with a teenager based on nothing and feeling as deep as a contact lens case. Instead of evolving personalities searching for their truest selves, we get characters who seem to have no idea who they are or were or might eventually be. Let alone why. People are depicted as villains or heroes only to change sides without visible motivation or consideration. It is confusing because you know how it should be, how the essence of the story requires it to be, and it goes other ways seemingly at random.

It is a film that starts with promise and ends with promises broken. That is about the only way that it is at all similar to the comic books. Although, in the comics, the promises are not made to you.

Nebraska, on the other hand, does something totally different with its familiar type of story. It sticks to the program. As the Supreme Being pointed out in his dismissal of the picture, it’s hardly fresh or innovative. I liked it anyway.

Nebraska, on the other hand, does something totally different with its familiar type of story. It sticks to the program. As the Supreme Being pointed out in his dismissal of the picture, it’s hardly fresh or innovative. I liked it anyway.

It’s not that what he says is incorrect. It’s that I had a different experience of the film.

It’s like this. Remember that favorite bedtime story we were discussing earlier? Maybe you made your parents read yours to you over and over again, like I did mine. You heard this story so often that you knew if your mom or dad skipped a line, or dropped a word. When they read the story to you, you were listening, but you were also not listening.

You were living in the world of the story, freed of responsibility to track its developments as you knew — by heart — what they would be.

Nebraska is not my favorite bedtime story. It is a tale of a standard type, with no dramatic surprises or unexpected developments. A father and son drive across a few states, quarreling and bonding, so that they can compare themselves against the world and come out the other side just ever so slightly wiser. The old man wants to believe he’s won a bunch of money, but he hasn’t.

In the case of Alexander Payne’s version of this oft-told tale you’d be challenged to find something novel in the story. The characters I found more compelling than Supreme Being did — certainly not cliché, which is a strong word — but far from complex or original, even if well performed for the most part.

All this being the case, my mind felt free to roam within the universe of the film. I noticed that which I mightn’t have if I was more focused on story. I found some surprise and novelty in variation and nuance.

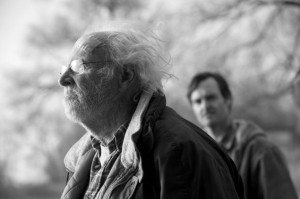

I got lost in the grayness of the cinematography; the lack of romance in the black & white imagery. I found myself considering the context of this story told at this time in American history. The subtlety of accent in a world overwhelmed by blandness.

As the story clicked through its paces, I checked its developments against my experience and that map was uncomfortably clear. You are here, it said.

And I laughed and scowled and nodded my head in familiar, unpressured, understanding. Unsurprised to find myself where I was, but more aware of my surroundings nonetheless.

You might posit that I brought my own importance to an unimportant film, and you might be right. One can rarely know what a director or writer or performer intended when he or she created their work. Maybe Payne was simply happy to drift through a well-worn picture book, reading it without serious investment. Or maybe he was using a familiar framework to investigate something so obvious it often gets overlooked.

A million dollars won’t make your life worthwhile, no matter how stubbornly you adhere to the idea of it. I’ll spare you my rant about rampant capitalism and greed. It’s as unsurprising as Nebraska.

But I care for it just the same. It’s part of America right now, at this instant. Its melancholy familiarity doesn’t make it meaningless. It makes it a good bedtime story.

I had, for a brief moment, considered renting Wolverine. I am considering it no longer.

I wonder how it would land with someone who hadn’t read the comics. To me, it was worse than without sense. It was deliberately working against the sense inherent in the story.

And it was totally goofy with only a few, rare moments of decent storytelling. The very beginning is good, in Nagasaki.