Here is an exchange commonly heard when out socially with the Doctor Missus.

Dr/Mrs: I am a marine biologist.

Everyone: Do you study dolphins?

No. The Doctor Missus does not study dolphins. Or whales, or sharks, or anything else that falls into the category she and her peers disparagingly refer to as ‘charismatic megafauna.’ (Instead she studies the little sea chiggers that infest your eustachian tubes every time you hold your ear up to a sea shell. That’s why those attractive exoskeletons of deceased soft-bodied organisms sing the song of sea. I think. I am not a marine biologist.)

I bring all this up because today’s Mind Control Double Feature tells the story of two particular specimens in the charismatic megafauna category. While the specimens themselves would be hard to mistake for each other if you met them on your way into the surf, the stories about them—if you allow your mind to swim out a ways—are stunningly similar. Once you have become aware, you will never see either film in the same way again.

Both will be forever wed to the other, like a foolish sailor to Davy Jones’ locker. Like Scylla to Charybdis.

I am, of course, talking about Disney’s treacly animated tale of fantasy romance—The Little Mermaid—and the horrific documentary exposé of corporate immorality—Blackfish.

The Little Mermaid (1989)

Oh to be part of your world!

Oh to be part of your world!

That’s the dream that young Ariel—a perky, red-haired mermaid princess—clings to in Disney’s blockbuster. Perhaps you’ve seen this film? Maybe you were a young girl when it hit theaters and you fantasized, like Ariel, that you could escape the claustrophobic clutch of your overprotective father (Triton, King of the Sea) to walk the world of men and marry a dashing prince?

I had no such dream. I also hadn’t ever seen The Little Mermaid until last week.

Watching it for the first time as an adult, I thought: huh. That’s a weird damn film. Not Mary Poppins weird, but weird and strangely heartbreaking.

In the picture, Ariel is captivated by humanity. That’s the essential thrust of the story. Despite being warned by her family of the danger, she swims too close to human vessels. She goes so far as to pull one soaked mariner around in the froth before abandoning him on the shore, her song still bubbling in his ears, the water still swelling in his lungs.

Remember that image. It will come back around in our second feature.

Although Triton assigns a good-hearted chaperone to keep an eye on Ariel, this tiny crab, Sebastian, proves completely ineffectual in providing even the slightest hint of protection to her. The Little Mermaid is taken in by the false promises extended by Ursula, a half-cephalopod / half diva sea witch.

Ariel gets tricked into man’s grasp even though it will cost her her voice.

Her song is stolen from her in exchange for nothing more than the fickle affections of man. For the bulk of what should be the heart of the story, not a word is spoken by Ariel. She is limited to dumb mimes and parlor tricks, attempting to win the genuine care of the prince who can save her from utter ruin.

Remember that image. It will come back around in our second feature.

And does Disney’s film have a happy ending you meekly inquire? Of course it does! Ariel gets exactly what her heart cried out for: freedom from her family, access to all the useless filth of humanity, and a kiss from a man whom she’s known for three days. A kiss from a man who now rules her forever.

Hooray for Ariel!

As you know, The Little Mermaid is based on a classic tale from Hans Christian Andersen. In the original version, the sea witch is no harridan, Ariel is not fascinated by the world of man, walking causes her excruciating pain, and the prince threatens to marry someone else anyway. The sea witch sends Ariel a magic knife—if she kills the prince, she can regain her life as a mermaid. She can’t do it, though. The prince marries someone else. Ariel throws herself into the sea and dissolves into sea-foam.

Hooray for Ariel!

There’s some tacked on ending about Ariel discovering she can earn her own soul and rise up unto god, blah blah blah but scholars—of which I am not one—look at it askance.

So you see why Disney altered the story just a wee bit. They added songs and a frisky little flounder and some evil moray eels and a dramatic conclusion in which everyone lives happily ever after in a deluded, unsustainable dream.

It’s not a bad film. The Little Mermaid kicked Disney animation back into gear after a long slump. But it is oddly wrong. It’s as if someone took a desperately tragic tale, shook some glitter and color over it, and hoped no one would notice that the dream it purveys is sick fantasy.

Remember that image. It is the world revealed by our second feature.

Blackfish (2013)

SeaWorld has, for decades, been lying to everyone—the public, its staff, the government—in order to keep its vastly popular but fatally dangerous orca show going. Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary Blackfish rams this message home like an animated prince steering a sunken ship’s broken bowsprit through a titanic sea witch’s abdomen.

SeaWorld has, for decades, been lying to everyone—the public, its staff, the government—in order to keep its vastly popular but fatally dangerous orca show going. Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary Blackfish rams this message home like an animated prince steering a sunken ship’s broken bowsprit through a titanic sea witch’s abdomen.

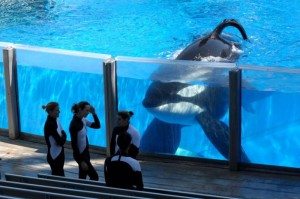

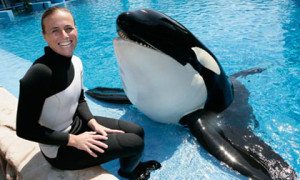

Cowperthwaite focuses on the tale of one particular specimen of charismatic megafauna, the killer whale called Ariel. I mean Tilikum. The orca’s name is Tilikum, unless you speak orca, in which case his name is likely forever lost as he will never see his family again, trapped as he is in the world of man.

While I have no problem plodding out the plot of The Little Mermaid, I won’t do the same for Blackfish. I don’t need to. It’s the same story. A creature from the sea is lured into the world of man, despite the danger. His chaperones—in this case, not crabs but equally ineffectual trainers—fail to keep him from being closed off from the sea and his pod. His voice is taken; that which makes him vital and free. Although Tilikum does his best to win the heart of the fickle prince—SeaWorld—his marriage does not work out as his fanciful young heart might have hoped.

He is captive of humanity. He is assaulted. And he does what any sane person should realize a creature such as Tilikum or Ariel would do when locked in the endless hell of an uncaring embrace. He vents his anger. He longs for the sea, for his people, for release.

Blackfish is The Little Mermaid, just a version that lasts beyond the farce of a wedding. How anyone could watch either film and not see them as equally heartbreaking is beyond me.

In the case of the documentary, Cowperthwaite does an admirable job of assembling facts and footage that is nothing short of completely damning. SeaWorld has oozed out a pathetic response, but anyone who can’t see through the public relations bullshit should feel free to take a swim with Tilikum. Perhaps they will find themselves abandoned upon the shore, his song still bubbling in their ears, the water still swelling in their lungs.

How come the Dr. Missus doesn’t have a degree in mermaidology? That’s an even better career move than giant snails.

Meanwhile, this sounds like a very educational double feature. If only they had a Sing Along Blackfish night at the Castro.

She was going to study mermaidology but couldn’t make it all of the way through Splash.

i haven’t watched the little mermaid, but have been on the ride with snapper and buckaroo about, oh, a hundred times. does that count?

Yes. Now you just need to go on the Blackfish ride a bunch to even things out.