What do you do when mere drama isn’t enough? When anger isn’t angry enough? When love isn’t lovey enough? When you want not only to underline every word, but to italicize it, boldface it, and write it in all caps in 72 point font? When you want to guarantee that even that old, half-deaf man in the back of the house understands that every word you say is the most imporant, most emotionally fraught, most unbearably meaningful thing ever said by any human anywhere ever?!

In such a case as that, one must resort to melodrama. Melodrama! A drama so dramatic, it makes drama look downright undramatic! The kind of drama that beats you over the head with itself, that yells in your face, that reaches down your throat, grabs your heart in its big, meaty hands, yanks it out, shakes it in your face and squeezes it so goddamn hard it pops! That’s melodrama.

In this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, we dive deep into the melodramatic with two very different movies. Different but for how far over the top they go. Both take off from the get go and never come down. Hold on tight.

Shock Corridor (1963)

Samuel Fuller didn’t screw around with his movies. The man had something to say, and by god he was going to say it. He rose to prominence making war movies and film noirs, but butted heads with studios often. He wanted to explore more controversial ideas, and had to go low budget to do it.

Samuel Fuller didn’t screw around with his movies. The man had something to say, and by god he was going to say it. He rose to prominence making war movies and film noirs, but butted heads with studios often. He wanted to explore more controversial ideas, and had to go low budget to do it.

Between such gritty flicks as The Crimson Kimono, Underworld U.S.A., and The Naked Kiss (and a decade after his most famous noir, Pickup On South Street), Fuller wrote, directed, and produced what might be the best movie he ever made.

Shock Corridor starts off insane and never lets up. I watched the entire movie with my mouth hanging open in disbelief. That is not an exaggeration.

We open with reporter Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck) being quizzed by a psychiatrist. Johnny’s in training, has been for a year, to fool a mental hospital into thinking he’s insane. He wants to be committed. Why? Because a patient was killed inside, and no one knows who did it. Three inmates witnessed it, but they’re nuts. Johnny thinks if he’s in there with them, he can solve the crime, write the story, and win the Pulitzer. He sees his plan as a short-cut to fame, his one goal in life.

With a plan like that, what could go wrong?

I don’t think anyone can watch this movie and not know from scene one what’s going to happen at the end. The great pleasure of Shock Corridor is watching how it happens. Needless to say, it’s a melodramatic journey.

The acting in Shock Corridor is through the roof. Constance Towers plays Johnny’s stripper girlfriend, Cathy. In the opening scene, she actually eats every piece of furniture in the room as she tells Johnny he’s mad to go through with such a plan, a plan that requires her help: she has to go first to the police and claim she’s Johnny’s sister, and that he tried to rape her, and then to the psychiatrist at the hospital, and say Johnny’s wanted her sexually since they were kids.

She goes through with it. Johnny fools the docs. He’s in. But the problem with the madhouse is that everyone in there is mad. Kinda gets in your head, doesn’t it, Johnny?

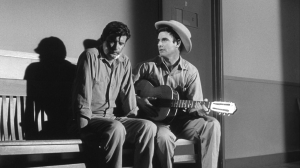

Each of the three witnesses to the crime gets his own showpiece scene, with a long, riveting speech. These scenes are not like normal scenes. They are long and intense and in two cases the loony witnesses relate their dreams, shown in color, adding a totally bonkers surreal element to the movie. Speaking of surreal, I might also mention Johnny’s sleeping visions of Cathy:

Though the melodrama in Shock Corridor is at times so outrageous you can’t help but laugh, it’s not meant to be funny. It’s used to heighten emotions—to the extreme. Fuller wants to punch you in the head. And that he does.

A final sequence might be said to take place inside Johnny’s head. Things have gone a bit off in there. You’ll see.

Written On The Wind (1956)

From the low-budget black & white of Shock Corridor’s mental institution we go now to the deep, lush colors of melodramatic Texas, in this outrageous classic from director Douglas Sirk.

Sirk essentually invents the modern soap opera with Written On The Wind, though unlike soaps, he’s in on the joke.

I could imagine people then and now watching Written On The Wind and seeing it as an overacted bore, featuring a bunch of jerks and their stupid problems. But if you pay just a little attention, you’ll realize that Sirk is up to something a lot smarter. The melodrama of Written On The Wind, unlike in Shock Corridor, is by all means meant to be as funny as it seems. Sirk aims to comment on what he sees as the overwrought, self-important dramas of the ‘50s, both cinematic and theatric, by creating a movie that amps up that self-importance as high as it can go.

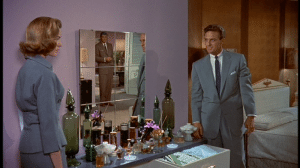

Written On The Wind is, above all, a fake. The colors are outrageous, the sets are outrageous, everything is overdone Hollywood schmaltz. I mean I hate to give anything this good away, but look at this image and tell me Sirk doesn’t know what he’s doing. The woman is Marylee (Dorothy Malone), alcoholic, nymphomaniac daughter of oil baron Jasper Hadley:

Not much subtle about that, is there? But maybe if it was the ‘50s, the symbolism wouldn’t jump out at you quite as bluntly. Sirk walks the line just enough that at moments you wonder if you’re supposed to be taking things seriously. And then an image like that comes along and you know you’re being taken for a glorious, outrageous ride.

The story is, of course, overheated, tempestuous, and salacious. Marylee’s brother, also an alcoholic, is Kyle (Robert Stack). They’re both emotional disasters, ruined by their inherited wealth. Their father the oil baron thinks they’re both worthless. Kyle marries Lucy (Lauren Bacall) on a whim and fights with Marylee’s beau, Mitch Wayne (Rock Hudson), who’s secretly got the hots for Lucy. Mitch is the geologist in charge of daddy’s oil operation, and a childhood friend of the family.

Well, after that we’ve got a low sperm count rearing its ugly head, a mysterious pregnancy, adultery, murder, false accusations, and a trial, where everything comes out in all its hoary detail. Everything you could ask for is given, times ten.

Written On The Wind is the best kind of subversive satire. It mocks its own time. Making fun of the ‘50s today would be easy, and pointless. Actually doing it in the ‘50s, taking down the era’s serious and important dramas in a way just underhanded enough that many at the time (and since!) didn’t notice—now that is a neat trick.

Watching these two masterpieces of melodrama may leave you overwrought. I suggest keeping plenty of whiskey within easy reach at all times during this screening.

Hmm . . . I just watched both (not in the same night, but within a couple weeks of each other). I’m not convinced by the popular interpretation of “Written On The Wind” as satire. The style is exaggerated, but I’m not convinced it’s supposed to be ironic. The effect Sirk said he was going for was “surrealism.” I was actually into the film by the final act. I gave a crap about what was going to happen.

Shock Corridor, not so much. It was an interesting experience, but one crucial detail made the whole thing unravel for me: When she visits him in the mental institution, she acts–and expects him to act–like they’re lovers, not brother and sister. But they’re not in private, and they have every reason to keep up the brother/sister charade. You might say they just overlooked that, but I don’t think so. They needed to give her some reason to approve the shock therapy. She had to have some reason to think he was actually going crazy, but the story didn’t give them any options. Any time she saw he, she should have expected him to act crazy, since that was the ploy. Tough dilemma. (Of course, there’s also the fact that the entire premise of the movie is astoundingly stupid.)

I got the news of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death via text message tonight while I was at the cinema watching “The Wolf Of Wall Street.” I’d like to see that film as a satire on the excesses and superficiality of Hollywood–Scorsese is playing his audience for fools, just as his hero does–but I’m not sure. It would be interesting to compare “The Wolf Of Wall Street” and “Written On The Wind.” Maybe neither is satire, maybe both are; but there are very interesting parallels between them regardless. Anyway, I’d like to be able to blame the same excess and superficiality for Hoffman’s death. I’ll think more about it tomorrow. Right now I don’t feel much of anything, for some reason.

The beauty of Written on The Wind is that it walks a fine line. But there are too many giveaways not to see that Sirk knew what he was up to, not least of which is what you point out, that he said he was going for surrealism.

Wolf of Wall Street is certainly sending up the emptiness of those in the financial world. Not sure where you see it sending up Hollywood.

I guess I just don’t get the satire of Written On The Wind. What is supposed to be the point and how is it supposed to work?

I’m not sure Scorsese was trying to criticize Hollywood, but I’d be happier with the film if that was his intention. I’d like to write at length about it, but here a few key points: When DiCaprio is reeling in his first big fish, and his employees are behind him chuckling, he is playing to the audience. You could read it as us being the big fish, being reeled in, knowing it’s a lie and still laughing along and rooting for the con artist. This scene contrasts with the end, when the eager and hopeful yet painfully incompetent audience is looking up at him, to him, for guidance. Are they dupes, or are they about to learn well-worn trade secrets from a master? That’s the position the audience is in: is the audience a fool to fall for a hero like Belfort, or can he teach us something about how to play the game?

Scorsese sells us Belfort using extreme sensationalism and absurd scenarios without ever developing real, living, breathing characters. For example, Naomi’s aunt dies, Belfort insists on taking her yacht through a storm, which leaves her shocked at his obvious lack of sympathy, and when he then sinks her yacht, she . . . dances with the Italians who rescued them. Absurd. And him crawling on his face as she masturbates–in isolation, it could be a compelling scene, but at that moment in that film, it’s utterly absurd. The characters and drama are a ploy to sell us Belfort. From that point of view, either Scorsese was in on the ploy, or he wasn’t. I’d like to this he was, but I’m not sure.

*I’d like to think he was

Ok, I just wrote up my thoughts on The Wolf Of Wall Street, with spoilers.

I think what you note about the emptiness of the characters is all exactly right, but I still don’t see why we need to make the jump to saying the commentary has something specifically to do with Hollywood spectable. Certainly Scorsese knew what he was doing: he made a movie about empty, sad people imagining they’re living the good life, knowing full well that this awful life is exactly what our culture says we should be striving for.

Look at all of the people outraged at what they saw as a glorification of Belfort’s lifestyle. That fact alone points to how right on Scorsese’s skewering of that kind of excess is. We have been so conditioned to seeing that kind of behavior as desirable that we watch the movie imagining it’s promoting Belfort’s ways, then voicing outrage at it, knowing deep down that surely it must be wrong.

I didn’t much get into the movie, since it was about empty characters I cared nothing about, but certainly the point of the movie is that it’s about empty unlikeable characters. The scene at the end is showing us as clearly as can be that many of us are indeed those very people in the audience, who want desperately what Belfort had.

It is impossible to take Robert Stack seriously after Airplane.

Written on the Wind is insane, but I think I liked All That Heaven Allows better. Except for the scene in which Marylee remembers/acts out earlier days at the river solely using her mouth. That’s comedy gold. Also, Robert Stack makes an excellent drunk.

Robert Stack is comedy gold. I’m not sure which one I like better. Both are marvelous.