If I asked you to name a famous science fiction movie that before its release was bastardized with dreary, useless voice-over and a tacked-on happy ending, I suspect you’d come up with Blade Runner. And reasonably so. Famously, Ridley Scott was given a chance a decade after its release to right the wrongs and put out the movie he’d originally meant to make. In so doing, he pretty much invented the concept of the “director’s cut,” which for most movies since exists as little more than a marketing tool to sell you more DVDs.

For Blade Runner, the director’s cut saved the movie. In part, this is because Scott removed elements from the original release. Most directors add material, because as everyone knows, more is better (see Donnie Darko for a prime example of a director’s cut ruining an already wonderful movie).

This is all well and good (or annoying and bad, I suppose) for movies made in the past twenty-odd years. Everything shot is saved. No negatives are thrown out (that is, no digital files are deleted). Nothing is lost. Otherwise how would we get to watch twelve hours of The Hobbit on our iPads?

For movies made in the olden days, i.e. anything before, say, the 1980s, there’s little chance of seeing a single outtake from any movie, let alone a restored or re-edited version of it, good or bad. Famous restoration jobs are few and notable. Lawrence of Arabia and A Touch of Evil come to mind.

Speaking of Orson Welles, many consider his follow-up to Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, the greatest cinematic tragedy of all time. Welles made a long, unique movie, and the studio hated it. They axed forty minutes of material, shot a new ending without Welles’s involvement, and re-edited the movie as they saw fit. The cut material? Thrown out. Gone forever. It’s still a beloved movie, but imagine what we’d be saying about Welles’s director’s cut if he’d ever been able to make it. I’m guessing we’d have liked it.

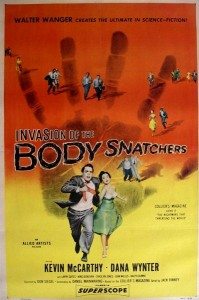

Which brings us to Invasion of The Body Snatchers (’56), adapted from Jack Finney’s book, The Body Snatchers. Like Ambersons (and I hope you’ve been waiting as long as I have to see these two movies in the same sentence), Invasion of The Body Snatchers is, no matter what was done to it, beloved. It’s an (almost) perfect science fiction film. I loved it when I was a kid, when it creeped the hell out of me, and I love it still as an adult. It’s simple and smart and unsettling in the best way.

It’s also, like the original release version of Blade Runner, not the movie it was meant to be. And for exactly the same reasons: unnecessary voice-over and a tacked-on happy ending. Do the studios ever learn? No, they do not.

Invasion of The Body Snatchers begins in a police station with a seeming madman ranting about pod people. This is Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy). A psychiatrist is called in to hear Miles’s story. And so we go back in time, and the movie unfolds in flashback, as related by Miles.

Which is a very safe way for a horror/science fiction film to unfold. In the past. It already happened. It’s behind us. It can no longer hurt us. We are removed from the events taking place.

Already, what a loss. Then the voice-over comes in. If you make the mistake of really listening to it, you’ll notice how useless it is, how it comments on what we’re already looking at, and, worst of all, how it harps on the weirdness to come. Once again, this is a tactic to make the audience feel safe and coddled. Instead of watching a story where the weirdness creeps in slowly, we’re told over and over from the outset that something terrible is happening.

You’d think the movie’s name would have been enough to clue us in.

Without the opening scene and the voice-over, the movie would begin at a train station. Miles returns from a trip, talks to his secretary, who mentions a number of people desperate to see him.

At his office, many of those desperate people have suddenly cancelled their appointments. The few that haven’t have the same complaint: their father isn’t really their father, their wife isn’t really their wife, and so on. Seems to be a strange delusion going around town.

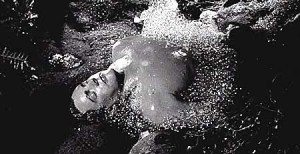

This all unfolds with a perfect build, all the way to the first reveal of a faceless, fingerprintless, half-formed pod-person lying on a pool table. Is it an alien copying Miles’s friend? Or is it a murder victim with its fingerprints filed off? Once the police show up, Miles and his friend aren’t so sure. Their version seems so fantastic, the police version so logical and mundane.

For a ‘50s science fiction flick, this is all remarkably nuanced. Director Don Siegel and screenwriter Daniel Manwaring create characters who realistically shy away from assuming anything odd is the result of space monsters. They question themselves. When the voice of reason—the policeman—makes logical sense of what’s happening, they have to admit he must be right.

And then the voice-over is there to remind us that NO! Its not so simple! Something horrible is eating away at the mind of our hero! Because we never would have noticed that ourselves. All of that careful build and subtle nuance, steamrolled by voice-over. Not only that, but voice-over by a hero we know survives to tell us his tale.

Lucky for us, even with the obnoxious voice-over the movie works. But upon my most recent viewing, it annoyed me more than ever. It explains what doesn’t need explaining, and warns of what we’re going to find out anyway. It was put in because test audiences were confused. Sigh. For as long has Hollywood as existed, they’ve had test audiences, and for as long as there have been test audiences, they’ve been confused by and angry with anything not exactly like what’s come before. The result? The rest of us suffer.

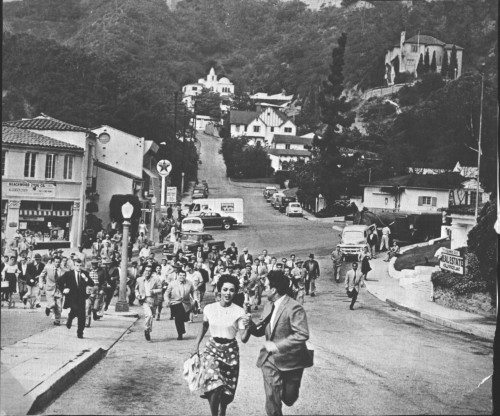

The intended ending of Body Snatchers remains one of the most memorable scenes in movie history. Miles, driven mad by pod-people and lack of sleep, escapes the sleepy town of Santa Mira and runs into the middle of the highway, where he rants and raves at the passing cars. He leaps on a truck bound for Los Angeles—and finds it loaded with space-pods. He leaps off and screams, “They’re here already! You’re next! You’re next!” He screams it right at the camera, right at the audience. Cut to black.

Only no, don’t cut to black. Cue wavy flashback screen to return us to the present. Miles has finished his story. The shrink thinks he’s nuts—but then word comes in of a weird traffic accident. A truck crashed—a truck full of weird, giant pods! The cops call the FBI. Miles is vindicated. Everything’s going to be fine. The end.

Talk about a monstrous theft. One of the all time great endings, and it’s snatched away before our eyes.

Worse still, no alternate version of the movie has ever been released. It wouldn’t be hard. Simply by removing the framing scenes and the voice-over, you’d have essentially the movie intended by Manwaring and Siegel. I have no idea why this has never been done. It is time, oh holders of copyrights and suchlike peoples! I so decree it!

There. That ought to do it.

One of my favorite movies ever. Super creepy.

I didn’t know it was re-cut this way. Now I hate it.

Thanks a lot, Mind Control!

We aim to please!

And also, it’s still one of my favorites too. I just bought the blu-ray and watched it and it was beautiful. Aside from the above…

We’ll said!

“We’ll?” FFS

Thank you so much for perfectly describing what happened in Siegel’s original director’s cut. Don use to tour the States with his Director’s Cut in tow. Siegel and McCarthy were both in attendance in Los Angeles and showed the original Director’s Cut at the MOMA. The scene that benefitted most was the transformation of Becky and it’s immediate emotional impact on Miles. Yes, the voice over in the theatrical version intrudes there as well. But when it happens in the director’s cut it happens to us then and there. Everything is heightened, the pathos, the suspense, the terror! It was astonishing! I believe this Director’s cut is still out there somewhere and have been trying desperately to locate a print. If anyone knows anything please contact me. My details are below.

I had no idea Siegel used to show his cut. My god I’d love to see that. And you’re right, if he used to show it, a print or better yet a negative must still exist. Keep searching!