In the book Introduction To Documentary, author Bill Nichols makes a bold statement: all movies are documentaries. From here he cleaves the mass into two big categories: documentaries of wish fulfillment (i.e. scripted narrative films) and documentaries of social representation (i.e. “documentaries.”) Whether doing so by using actors to portray human events or by turning the camera on people acting out their everyday lives, all filmmaking, he argues, engages with our shared cultural moment.

The 11th Annual Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, which just wrapped on Sunday, is one place to see how that moment is playing out. Held over nine days in Missoula, Montana every February, it has grown into one of the major American venues for new documentary work. (I attended the festival to show my film Tatanka.) This year it showcased about 60 new features from all over the world, as well as another 50 shorts and a retrospective of docs from the past. What does the world look like from the Big Sky stage?

For one thing, it’s a place where money seems to have ever more perverse impacts on our daily lives. From a disturbing look at the Koch brothers’ blitzing of the American political arena with cash in Citizen Koch to the plight of a single mom barely getting by in Paycheck to Paycheck: The Life And Times Of Katrina Gilbert to small Indian business owners being pushed out by mega-malls in Mallamall, there seems to be no arena untouched by filthy lucre.

It’s also a place where individuals achieve amazing things. Bending Steel profiles a man looking to break through personal issues by achieving uncommon feats of physical strength, Medora follows an unlikely group of small town heroes on a winless high school basketball team in Indiana, and The Whole Gritty City documents the aspirations of young members of New Orleans marching bands following Hurricane Katrina.

But it was the deep character studies that interested me most, and where the potential for documentary to provide true insight into our shared moment seemed to shine the brightest. In these extraordinary films, one sees the intersection of the personal and the political in profound ways that defy easy explanation.

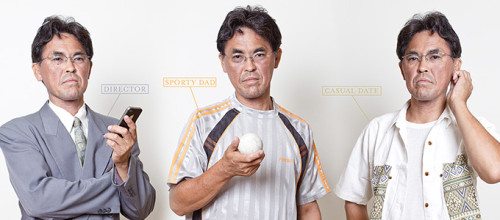

Directed by Danish filmmaker Kaspar Astrup Schröder, Rent A Family, Inc. profiles Ryuichi Ichinokawa, who has started a business in Tokyo providing fake family members or friends to clients who need them at ceremonies and other social functions. Is your wedding party not impressive or fashionable enough? Just engage with I Want to Cheer You Up Ltd. and they can provide you with attractive actors to play “best friends” and “relatives” to show off to your new in-laws!

The titillating premise was enough to draw a near sell-out crowd to the Crystal Theater on Saturday afternoon, but the film is not a sensationalized look at a bizarre business venture. Rather, it’s a nuanced character portrait of Ryuichi, a man whose inability to speak plainly to his own wife and children mirrors the predicament of his clients.

It begins with a surreal scene in which Ryuichi himself is hired to play a client’s husband in a negotiation with her ex over their joint child support fund. Ryuichi calmly plays his part with skill, speaking very naturally to his “wife” and chatting amiably about the children in question. By the end of the session, his straightforward manner and subtle references to his own modest means have done their work: the ex agrees to his client’s wishes to take control over the fund.

Later he is one of nearly three dozen actors paid a total of $25,000 to fill out a young bride’s wedding party. Pictures are snapped and bows are exchanged, and by the end of the night the bride has gotten her money’s worth by being in the company of a gaggle of adoring and attractive “friends.” Ryuichi himself is moved to tears by the ceremony.

Ryuichi enjoys his work, but when he returns home he finds mostly alienation and despair. His relationship with his wife is poor to nonexistent and he spends little time with his two children. The same societal expectations that have taken their toll on his clients have beaten him down as well, and he despairs about his inability to provide a consistent income for his family. No one—not even his wife—knows about the depths of their financial predicament or what he does for a living, and though his small house puts him in close physical proximity with others, he feels profoundly alone.

It’s the small details that make the film special. Ryuichi spends many quiet moments with the family’s tiny dog, and in these sequences one sees clearly Ryuichi’s capacity for intimacy. There is a scene where he stands for a brief moment near the railing of a bridge and the context alone is enough to make you wonder whether he might contemplate suicide. The moment passes, but in the very next scene he discusses exactly that. In clips that play in the background on the family television set, talk show guests debate the merits of honesty in familial relationships: is it better to tell the truth, or to uphold appearances and avoid conflict? With patient certainty, the film is masterful at bringing us into the heart of Ryuichi’s dilemma, and by the end we can understand why someone would engage his services even though they are clearly a short-term fix for a deeper societal ill.

An equally lonely character is at the heart of Jacob Dammas and Helge Renner’s mesmerizing Polish Illusions. The film shows how unnecessary it is to pander to an audience when you have characters as fascinating as Mark Buller. Mark is a retired Army helicopter pilot who now lives in the small Polish town of Darlowo and spends his days maintaining, repairing, and driving around the numerous military vehicles that populate his huge compound. It’s never clear how he came by these things or how exactly he makes a living off them, but Mark himself is certain of one thing: he’s living the dream.

Cocky to a fault and clearly in need of the adoration of others, he whiles away the hours suited up in his Army jumpsuit fixing big machines and talking with a young Polish acolyte named Michał whose need for a father figure makes them a perfect match.

The film spends equal time with another character from the same town. Jan Konstantynów is an 82 year-old magician trying to get back into the game. Once a staple of variety shows throughout the region during the Communist era, Jan now finds himself without purpose, as his act is neither quick nor flashy enough to secure any work on the open market. Heartbreaking scenes ensue in which we behold a man whose self-worth is pegged to the certainties of a social system long since vanished.

The above description suggests a profoundly dour film, yet Polish Illusions is full of delights. Yes, Mark is arrogant and oblivious, but when he gets his due by being left behind by a string of Polish girlfriends we can’t help but feel for him, and his small acts of generosity to Michal make him endearing. One brilliant scene has him talking over his girl troubles with a German friend who tries in vain to help him see how his lack of demonstrated interest in anything but his work is killing his prospects.

Jan is endlessly optimistic about his chances for fame and finally catches a break when he auditions for a local talent show. In a subplot that comes to an exquisitely satisfying conclusion, he seeks out information on his brother’s whereabouts by calling police departments in a string of Kentucky towns and speaking to uncomprehending operators who try to make sense of his broken English.

Intriguingly, the two storylines never intersect. There is no causal or functional relationship between the two men’s lives, and this makes the overlapping themes that much more subtle and profound. Mark has material wealth but is lacking the emotional tools needed to accomplish the task of finding a long-term companion. Jan has a wife but is searching for the certainties of a social contract that is now gone forever, and lacks the one thing prized more than ever: youth. The secondary characters that weave in and out of the film further embellish the theme of this strange historical moment when we seem to be capable of amazing feats but are missing one of the basics of human existence: a clear connection to a larger purpose.

Neither film quite knows how to accomplish a smooth ending. The desire for closure is a strong one, and each filmmaker feels the need to wrap things up in something of a hurry. Yet both films are graceful and soulful, funny and profound, and show why documentaries of social representation can be some of the most powerful.

Og usually goes by the name Jacob Bricca. He teaches filmmaking at the University of Arizona and also directs and edits documentaries. You have seen his work if you’ve watched Lost in La Mancha or stumbled upon his ode to action movie clichés, Pure. His latest film Tatanka will be released soon.

Excellent. I look forward to watching both when they (hopefully) find distribution.

As a documentarian, can you enlighten me? I’ve noticed the closure problem you mention before. Do you think this is because documentaries of social representation describe stories which do not often provide the type of closure that documentaries of wish fulfillment do; or because tight funding requires the filmmakers to stop capturing footage before they might otherwise wish? I suppose it will be a combination of both factors?

I think it has to do with who doc filmmakers perceive to be their audience. Though there is a lot of lip service given to “audacious” filmmaking and filmmaking that “pushes boundaries” by critics and festival programmers, most of them expect relatively traditional structures, and most of us feel that expectation. Doc filmmakers don’t live in a vacuum.

And let’s face it, there’s a lot to be said for the traditional “narrative arc” in a film–it’s very satisfying. I often feel that more “experimental” structures are really just an excuse for sloppy filmmaking. Achieving that sense of closure is a fine art, and it’s hard to get right. Endings are hard!