There is nothing quite so funny as an uncoordinated fat man wearing a Mrs. Howell mask chasing a screaming blonde around the yard while he’s wielding a raised chainsaw.

Wait. No fair. You read that sentence out of context. It belongs much later on in this article—after I’ve gone into how I just watched The Texas Chain Saw Massacre for the first time, 40 years after its release, and far outside of its historical context. And found it partly creepy and mostly goofy.

Wait. No fair. You read that sentence out of context. It belongs much later on in this article—after I’ve gone into how I just watched The Texas Chain Saw Massacre for the first time, 40 years after its release, and far outside of its historical context. And found it partly creepy and mostly goofy.

I’ll start again. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is one of those films that is lodged in the public consciousness as a wad of undigested gum lodges in your colon. Or is that just an urban myth? Either way: frightening.

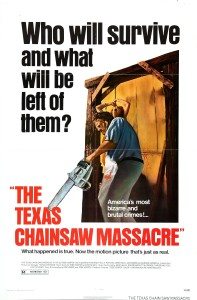

Tobe Hooper’s low-budget slasher film, released in 1974, added an overdose of adrenaline to the horror film market. Made for a pittance—with every pittance piece clearly evident on the pittance-pocked screen—The Texas Chain Saw Massacre made a fortune for everyone involved who had nothing to do with actually making the film. Its most memorable character, the skin-masked Leatherface, reigns over the horror pantheon with Dracula, Freddie Kruger, and the threat of watching Guardians of the Galaxy.

People went apeshit for the film. It spawned sequels and remakes and one particularly ill-judged set of Underoos. But, until recently, I’d never watched it. Although alive in 1974, my parents cruelly declined to take me to see The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

I had to rent the damn thing myself and it only took me 40 years to find a copy.

Taking the film out of context, it is fairly difficult to believe that this is the picture that I’ve been hearing so much about for so long. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre isn’t particularly scary, gory, or engaging. It is, however, occasionally genuinely creepy, genuinely interesting, and genuinely funny. It also has flashes of real style, even if they happen to be dripping gristle.

I’m glad I watched it.

The film tells a story so thin it’s hard to pad it into a full paragraph. A group of young adults wanders into the home of a family of psychopaths. One by one they are killed. Somehow, the final survivor manages to get away. The end.

That summary leaves out the best parts, though, which are all flashes of detail. Tobe Hooper’s film starts with a crawl of text, read seriously (and seriously!) by John Larroquette of Night Court fame. This text is total bullshit.

The film which you are about to see is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin.

It is all the more tragic in that they were young. But, had they lived very, very long lives, they could not have expected nor would they have wished to see as much of the mad and macabre as they were to see that day.

For them an idyllic summer afternoon drive became a nightmare. The events of that day were to lead to the discovery of one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

For audiences in 1974, cozying up to their honey for an evening at the drive-in theater (pronounced ‘thee-ay-ter’ in this sentence), this crawl of copy suggested many things that are as true as Comcast’s customer service pledge.

- That this story is even remotely based in fact

- That Sally and Franklin are somehow the main characters

- That there are, somehow, characters

- That all the youths die

- That the summer afternoon was at any time idyllic

- That ‘Chain Saw’ is two words

But after this fugazi—which did indeed capture the imaginations of America’s pimple-faced public—comes some of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre‘s best stuff. From prolonged black, we get flashes of light illuminating pieces of waxy corpses. It’s disorienting and gross, setting a ghoulish stage for what comes. Some madman has dug up graves and made a nice little modern art piece from rotting flesh. We see this sculpture in a long, lingering shot that’s warped with green, sickly sunlight.

So far, so good.

But then we’re in a van with five youths. None of them can act worth a damn, particularly Franklin (Paul Partain) who uses a wheelchair. He spends the entire film behaving like a seven-year old petulant idiot. Edits are oddly timed and rough. Shots are jerky. Events and dialogue are hard to follow or care about. The van stops to let Franklin piss into a tin can, but somehow the wind from a passing semi knocks one of the dudes over and sends Franklin and his chair careening down the hill. Which dude? I don’t know. One of them. Why is this scene here? Again, I don’t know. Outside of kicking off Franklin’s idyllic summer afternoon and ruining his shirt, it’s never referenced again.

The van swings by the cemetery to make sure grandpa wasn’t one of the abused corpses. He wasn’t. Phew! That would have made this idyllic day really sour. Luckily, there’s a drunk who cackles about horrible things and a good ol’ boy who helps Sally (Marilyn Burns) walk in a straight line by admiring how her boobs look through her tight shirt.

Those there look mighty fine, miss. You enjoy your cemetery promenade, now, y’hear?

Hooray! We’re off on a fun drive to see if grandpa’s corpse is wired to a pillar! Or did the kids have another destination in mind? I guess so, since they continue on, having conversations about nothing in particular, until they decide to pick up the least attractive hitchhiker in the history of the universe—and I’m including intestinal parasites in that category. This unnamed individual (Edwin Neal) is batshit crazy and the best actor in the film. He cuts his hand open with a pen knife, tries to sell Franklin a Polaroid he’s taken of him, then—his winning sales technique rebuffed—burns the picture with gunpowder in a nice, friendly back-of-the-van conflagration. Do the youths pull over in response to these shenanigans?

Nooooooooooooo. Why would you do something like that when you’re in such a hurry to get to, uh, that place where you’re going?

Anyway, the hitchhiker pulls out a straight razor, slashes Franklin’s arm, and that’s the last straw buddy! Nobody cuts someone other than themselves in our vehicle! Finally ejected, Mr. Hitchhiker smears blood all over the side of the van in some sort of occult symbol.

This is as scary as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre gets. The first third of the film, as rough as it may be, has an undeniable tension to it. Whatever nonsense is going on, it’s creepy and fucked up nonsense. From here, things just gradually and consistently slide into the ridiculous.

The van needs gas, but the icky gas station / barbeque joint is out of gas. They decide to go see the now decrepit home that Franklin and Sally grew up in, which is coincidentally and literally right around the corner. Why? Shhhh. There there. Don’t ask questions.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre immediately proceeds to the ‘let’s kill everyone off’ stage of the film. Normally, by this point, you’d expect to know who these characters are and what they want. Or at least know what their names are. This sort of information lets you empathize with a person and care if they live or die (hint: they’re going to die). Watching the film last night, I knew Franklin and Sally’s names. I knew they were related because John Larroquette told me. I also knew absolutely nothing else.

I could make you a list of all the things about these characters I did not know, but that would take a long time, so just trust me: they are people of indeterminate age and personality who are probably in Texas. All signs point towards them having a van.

While the character development in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre isn’t robust, that doesn’t mean the film lacks panache. It’s as rough as a low-budget feature can be, but Hooper has an instinct for composing shots and playing with sound. For example, when the van pulls up to pick up the hitchhiker, we leave the sweltering confines of the van for a longshot, framed square on, of the vehicle slowing to a stop as the hitchhiker gambols up to it. The sound drops out and blammo: eerie as hell. Other shots drop us down to knee level so we can look up at characters walking away from us while we nip at their heels. This makes everything feel off-balance and shows off derrieres nicely, but that’s purely coincidental, I’m sure. You’ve seen this shot in pretty much every other horror movie since.

Back in their old, rotting house, the four able-bodied members of the group ditch Franklin and screw around. Two decide to check out a swimming hole, but it has no water. So, naturally, they walk in the wrong direction to check out a weird house because maybe the people there will trade some gas for a guitar or something? Even the girl (Teri McMinn) thinks this is a stupid fucking idea. Probably because it is a stupid fucking idea.

Wouldn’t you know it? The guy (William Vail) pokes his head into the house where he is more or less immediately and without so much as a howdy-do killed with a sledgehammer by Leatherface. Why? Shhhh. There there. Naturally the girl wonders what happened to the guy, so she follows him into the house.

Here, we get one of the other marvelous parts of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

The girl (who does have a name; the internet says it’s Pam) stumbles through a curtain into Leatherface’s chicken and bone room. Well, what else would you call it? It’s full of bones and a chicken in a cage and some truly unpleasant taxidermy stuff, like a goat-skull-marmot-toboggan. Or something like that. There were a lot of bones. And a chicken. We spend about four hours touring the room slowly as Pam gurgles and screams and wards off evil with complex sigils and incantations. I want to meet the guy who designed this room so I can refuse to shake hands with him. It’s pretty awesome.

Unfortunately, Pam expresses her non-constructive criticism of Leatherface’s found art gallery and he overhears. He grabs her and puts her on a meathook so she can watch him dismember her beau with a chainsaw. You will notice that ‘chainsaw’ is one word unless is has been dismembered.

Let us take a moment now to consider the Leatherface. Who is this man? What does he desire? Is he contemplative, or anguished, or misunderstood? I have no idea. I know he wears someone else’s face over his own, and I’m going to assume that it’s his mother’s because, if you were going to wear someone else’s face, you’d most likely choose your mom’s, right? (Sorry mom. I do not want to wear your face. I’m just speculating on a hypothesis. Can I borrow your paring knife?)

But Leatherface: WTF.

Answer: IDNKWTF.

These murders aren’t particularly scary. They aren’t particularly gruesome by modern standards. There’s little build of tension because they happen pretty quick. They’re just… kind of funny and also sort of dull. It’s such a ridiculous series of events befalling people you don’t care about that my reaction was to poke the dog and say, “Hey. Did you see that? That’s nutsy-cuckoo.”

Anyhoo, the other dude wanders off to find the first two and gets killed. Kids these days. Then it gets dark and Sally and Franklin start to get freaky-deaky because their friends are missing and/or chopped up in the freezer. They decide the best thing to do is not to walk around the corner to the gas station but to push Franklin through the thicket, down the gully, and towards the other house yelling and hollering and not wearing bras. What can I say? It’s 1974.

At this point, they’re most definitely going to be late to wherever they were going and miss the thing they wanted to do. Let’s say they were going to the ice cream social where they were going to play bingo and vomit off the bell tower. Seems reasonable given what we know of them, which is nothing.

Then, Leatherface somehow manages to creep up on Franklin and Sally with a running chainsaw. I’m going to say that again: Leatherface somehow manages to creep up on Franklin and Sally with a running chainsaw.

Franklin does not do so well in this encounter. His kung fu is strong, but: chainsaw.

Sally, being a genius, runs off into the night and quietly hides, knowing that there’s practically no way a psychopath with a running chainsaw and face on top of his own face will be able to find her in the underbrush at night. Oh wait. Sorry. No. She runs around screaming like a chicken locked in a cage in a chicken and bone room. Well, what would you call it?

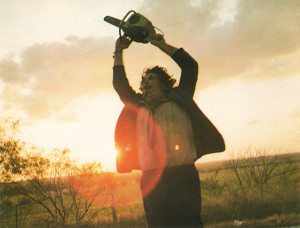

Also, Sally—now the lone survivor of the Texas Van-tastics—opts to run towards the house Leatherface came from. Good thing Leatherface is as fast as he is hygienic. And here, I really have to say, there is nothing quite so funny as an uncoordinated fat man wearing a Mrs. Howell mask chasing a screaming blonde around the yard while he’s wielding a raised chainsaw.

See? In context, it makes sense. I hope.

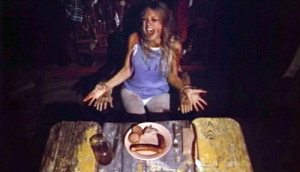

In the house is a vampire grandpa, a chicken and bone room, and a bunch of windows Sally can jump out of without opening them first. Also, man, does Sally have a set of lungs. She pretty much does not stop screaming until the film ends. The film does not end for a while though, and this is interesting. It’s interesting because all of the kids are dead but Sally, and because—story wise—not much is left to happen.

For most of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the editing is what we might call generous. If there’s a scene in which the information has already been conveyed, why not let it run on for an extra minute or two? Give the too-short film some length? This is nowhere so evident than in the final third of the movie. These scenes go on forever. Sally runs around the yard screaming for so long you stop wondering why she’s not running faster and start wondering if she should consider a career as a bike messenger. She wouldn’t even need a horn.

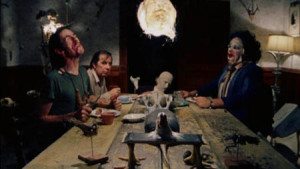

While people have attributed a ton of meaning to the scant framework of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre’s story, most of that is certainly wishful thinking. Here, however, the tale finally finds its meagre portion of meat. Sally escapes to the gas station, where it turns out the proprietor is (I think) Leatherface’s dad. He subdues her with a broom in one of the most hysterical pieces of slapstick comedy I’ve seen in ages. Then he drives her back to the Leathermanor, stopping to pick up the Hitchhiker, who of course is Leatherface’s brother. And then we get a nice little family drama.

Leatherface is mom, dressed as a woman and wearing mom’s face (I’m guessing). Gas station creep is dad. Hitchhiker is junior. And they drag vampire grandpa down from the second floor so he can suck the blood from Sally’s finger over dinner.

I ask you: What the what?

Is Hooper making some comment about the degradation of the American family? Is he high on fermented raccoon juice? Has the heat and misery of filming pushed this crew past the breaking point? (Yes to that last one; the stories about this shoot sound scarier than the film.)

In any case, family squabbles devolve into grandpa being assigned assassination duty—which means a papery dude trying to kill Sally with a hammer he can’t even hold. It is beyond preposterous. Everyone’s screaming. Everyone’s cackling. The chicken is agitated. The hammer keeps falling. I’m rolling my eyes so fast I’ve got the spins and, when I look up, Sally’s gotten away!!!

Still screaming, she jumps through another window, stumbles to the road, and manages to get the Hitchhiker run down by a semi. Leatherface chases her and the semi driver around for a while with his chainsaw (still one word) until some guy in a pickup truck spins out, lets Sally clamber into the bed, and takes off with Leatherface posing threateningly with his chainsaw as if he’s Rocky Balboa and not a fat dude wearing his mom’s face.

The end.

And that’s what it’s like to watch The Texas Chain Saw Massacre for the first time forty years after its release.

Did this film change the landscape of horror films? Absolutely. Is it—within its historical context—a crucial piece of cinema? Yes. Does it have style and wit and balls? Sho nuff.

Is it funny though?

Yeah. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is pretty funny.

Pingback: John Carpenter’s Contribution to the Slasher Canon·