I was a lucky child. Where I grew up, in Palo Alto, we had The New Varsity Theater, a rep movie house that showed double and triple bills covering the entirety of movie history. As an 11 year-old I saw a triple bill I’ll never forget: Stripes, Caddyshack, and Fast Times At Ridgemont High. (By the age of 10 I’d caught on to R-rated movies being the most entertaining.) The first two were or course co-written by Harold Ramis. He also co-starred in Stripes and directed Caddyshack. Prior to those two, he’d co-written Meatballs and what, in my considered 11 year-old opinion, was the finest comedy of all time, Animal House.

I don’t know how many other 11 year-olds knew the name Harold Ramis, but I sure as hell did. (My favorite director at the time (’82ish) was neither Lucas nor Spielberg. It was John Landis.) How could anyone not know Harold Ramis, I thought? He’s partly responsible for almost every funny movie made in my life!

And then? Then he directed Vacation, co-wrote Ghostbusters, and co-wrote and directed Groundhog Day. In the annals of comedy, has anyone had their hands in so many genius comedies? Woody Allen? Preston Sturges? The Marx Brothers? Not bad company to keep. So he’s got that going for him, which is nice.

He was 69 years old when he died earlier this week. Too young. It’s sad to think I’m entering the era where many of my childhood movie heroes are not long for this world. So I will think about other things. I will think about comedy.

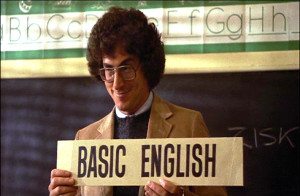

Ramis had a vibe about him, didn’t he? He was unflusterable. While Bill Murray and John Belushi and Dan Ackroyd and John Candy went nuts around him, he smiled his knowing smile, tossed out a subtly funny line here and there, stood back and watched. He was us. He was the audience, as amused by those loopy comedians as were we.

It was that kind of ability to stand back and watch that gave Ramis his knack for writing and directing comedy. He understood what was funny. He understood how to give his actors, Bill Murray in particular, exactly what they needed to do their best work.

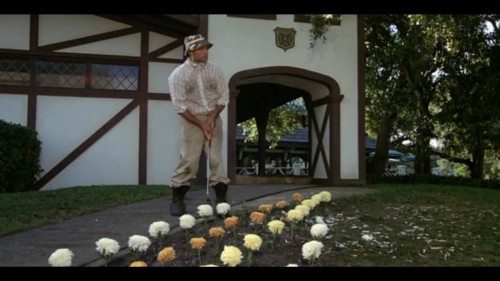

In Caddyshack, Bill Murray has a scene where he’s knocking the heads off of flowers like an insane golfer. No dialogue. Preparing to shoot it, Ramis took Murray aside and asked him if he ever, when alone, doing whatever, talked to himself in the voice of a sports announcer. Murray said, “Say no more.” And then he improvised the Cinderella story scene in one take. You know the one. If you don’t, what are you doing reading this? Watch Caddyshack!

As a kid, I watched Animal House, Stripes, Caddyshack, Vacation, and Ghostbusters over and over and over again. (Didn’t everyone?) I had posters on my walls of Vacation and Animal House. To this day I can quote the living bejeesus out of every one of these movies. Judd Apatow and essentially everyone he puts in his movies is in love with Harold Ramis (which love aided Ramis in casting Year One). Ramis’s scene in Knocked Up is the best scene in the movie, and Ramis improvised the whole thing.

There was something Buddha-like about Ramis. No surprise, then, that he made Groundhog Day, a movie hugely popular among all variety of religions, and psychiatrists, too, all of whom find the story of Bill Murray living the same day over and over again profoundly metaphorical. Not until Murray finds inner peace and contentment is he allowed to escape his infinite loop.

Groundhog Day doesn’t look especially good—Ramis was never a visual stylist as a director—but he more than makes up for that with great writing and editing. Groundhog Day plays effortlessly, but it took an extensive rewrite for Ramis to build the endlessly repeating days into emotional and comedic peaks. With a day that repeats ad infinitum, the possibilities are endless. How to find the funniest rhythm? And not only funny, but grim and desperate, too? It’s not an easy task.

Ramis made everything look easy. He peopled his movies with slobs and losers who were anything but losers. At the end of Animal House, we learn that the Deltas go on to be senators while the Omegas are murdered by their own troops in Vietnam. In Stripes, it’s Murry and Ramis whose division of misfits wins the battle. The Ghostbusters, though they may begin the movie as morally loose scientific frauds, become the greatest comedy heroes in history. In Vacation, Chevy Chase and family get their day at Wally World, park closure be damned. In Meatballs it just doesn’t matter. And in Caddyshack, everybody gets laid. Ramis’s characters, no matter how uncouth, no matter how obnoxious, and no matter, on reflection, how tirelessly they trash every supposedly important societal institution there is to be trashed, are utterly loveable.

In more recent years, I kind of lost track of Ramis. His later movies didn’t do much for me. At least not the ones I saw. This matters not at all. Ramis made my childhood funny. He saw to it that I’d never take anyone in authority seriously. He was the ball.