The best alien landscapes don’t exist on imaginary planets. They exist on earth, in both time and space. Think of all the places that once were you’ll never visit. You’ll never visit most of the places that presently are. In fact you can’t. Because a moment from now, everyplace will be someplace else. A city might exist one way today, and another tomorrow.

For example, someone might blow it up. It’s been known to happen. Humans love blowing things up and watching them burn. Fire is pretty so long as it’s not, for example, on you. It’s kind of a bother then. But you know what looks really grand on fire? Oil wells.

How can you beat the wonder of a burning oil well? Giant spewing plumes of flame billowing thousands of feet into the sky. It’s like we dug down into the earth only to hit a vein of pure fire. Oops. No putting those out, not without taking extreme measures. Might be safer to let them burn.

So. Where’s this intro going? I’m glad you asked. Because I’m just about to figure it out myself. This week’s Mind Control Double Feature presents two foreign worlds, and the fiery oil wells in their midsts.

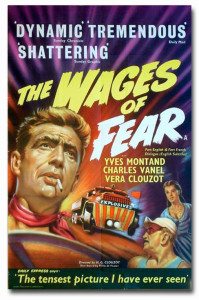

The Wages of Fear (1953)

An out-of-control, burning oil well is at the center of The Wages of Fear, director Henri-Georges Clouzot’s suspense movie to end all suspense movies. We don’t see the well until the very end, but it’s there from the start, waiting to emerge, and to give direction and hope to the poor bastards living in the South American (country unknown) town of Las Piedras.

There’s no work in this little muddy town. Stragglers from around the world linger at the cantina, buying nothing, sweating in the heat, wishing for any way to escape. It’s not a world you’d want to visit.

Prime among those hoping for a chance to get out are Frenchman Mario (Yves Montand), a handsome fellow who treats his sort-of girlfriend, Linda, with indifference; Jo, also French, a one-time high roller, now destitute, but still treated as though he had power and money; Bimba, a blonde German tough guy; and Luigi, a jolly Italian, the only one with a job—he’s a bricklayer with lungs full of cement. They’re all equally desperate.

The other notable occupant of the town is an American oil company, SOC, run by a cynical bastard, O’Brien. When one of their wells—located many miles away—catches fire, there’s only one way to put it out: blow it up with nitroglycerine. Problem is, how to get enough nitro out there in time? They’ll need to drive out two truckloads of the stuff (if one truck blows up, there’ll be enough nitro on the other), but the roads are so bad, the stuff will almost certainly explode on the way, killing the drivers. No union drivers would take that risk. So O’Brien offers to pay $2,000 to any man in town willing to do it. He knows they’re desperate enough to do it.

The four eventual drivers are the men named above. Once they get in their trucks and head out, every second of The Wages of Fear is a nailbiter. All they have to do is hit one bad pothole, and BOOM! They’ll be turned into paste.

It’s the kind of journey one is inclined to call existential. It’s as though these men have signed a deal with the devil. They drive a road full of ever worsening obstacles, which road only ends when they reach the billowing flames of hell.

“They”? That assumes anyone makes it alive. Is it possible to survive the road to hell, once you’ve set out on it?

I’ve seen The Wages of Fear many times, most recently in a beautiful 35mm print at the Noir City Festival. It’s longer than two hours, and not a bit dull. Hitchcock may be the Master of Suspense, but I’m not so sure he ever ratcheted up the tension the way Clouzot does in this, the best French action flick ever made.

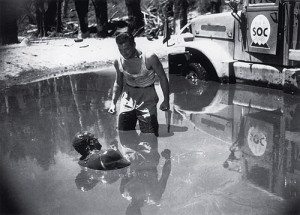

Lessons of Darkness (1992)

Welcome to hell. The Wages of Fear ends with a burning oil well. Werner Herzog’s sort-of documentary Lessons of Darkness begins with an entire landscape of them, and never shifts its gaze.

The subject of the movie is ostensibly the burning oil fields left in the wake of the first Iraq war, which Herzog (along with intrepid cinematographer Paul Berriff) films with outrageous beauty. But like I said, being a Herzog movie, calling it a documentary is a bit disengenuous. It’s not a doc; it’s Herzog. He refers to it as a science fiction film:

Calling Lessons of Darkness a science fiction film is a way of explaining that the film has not a single frame that can be recognized as our planet, and yet we know it must have been shot here…The film plays out as if the planet is burning away, and because there is music throughout the film, I call it ‘a requiem for an uninhabitable planet.’

It is not a political movie. Herzog never even indentifies the country as Iraq. It’s centered almost solely on the fires and the firefighters trying to put them out. There is some footage of Iraqi war victims, but Herzog was unable to film many of them before he was kicked out of the country. The Iraqi government had begun to suspect that maybe he wasn’t making a feel-good movie about Iraqi reconstruction after all.

What was he making? It’s a very strange and dreamy movie, reminiscent in vibe to his early desert movie, Fata Morgana, and his later sci-fi movie, The Wild Blue Yonder. Herzog narrates the images as though he were an alien visiting another planet, describing the people he sees as “creatures,” and extemporizing creatively on their probable thoughts and reasons for their actions. Is this documentary, or something else? Herzog has often spoken of his disdain for so-called cinéma vérité documentary making and its “accountant’s truth.” Herzog is interested in what he calls “poetic truth.”

Lessons of Darkness opens with a quote on-screen, attributed to Blaise Pascal: “The collapse of the stellar universe will occur—like creation—in grandiose splendour.” A perfect quote to open this movie of burning landscapes. Perhaps even more so when you consider that Herzog made it up. As he says, “Pascal himself could not have written it better!” Herzog wanted the film to open by introducing an element of poetry, to set the stage for the kind of film to follow. That Pascal never actually wrote the words is beside the point.

Like many of Herzog’s sort-of docs, Lessons of Darkness is a short movie, only 50 minutes long. Which is plenty of time to spend in the devastated landscape he presents. Coming on the heels of The Wages of Fear, it’s as though those men drove us here, and left us to burn. Exactly what message to take away from Lessons of Darkness is unclear. You’ll have to decide for yourself what it means.

Pingback: Europa Report And The Irreality Of Found Footage | Ciencia Ficción en Ecuador·