It is very difficult to determine with absolute certainty whether or not you are part machine.

Looking at you now, it’s hard to tell. You might be an old school hunk of metal with a living, throbbing human brain secreted inside. It is possible, on the other hand, that underneath your soft, fragrant skin you are comprised of nothing more than leftover stereo components. You could even just be a cleverly disguised digital watch with eyelids. These things happen.

One good way to test your possible androidishness is to go see Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen. If you fail that test; i.e. actually go to see that movie because I just suggested it: you are probably at least somewhat mechanical.

I am both sorry and not sorry.

Being an android can be fun!

If you’re an android, for example, you might be able to fire your fist at giant dragon-shaped alien battle cruisers so that your fist shoots like a rocket and then explodes into magic fingers of death which save the planet from slimy, alien-inflicted doom. Go try that now. If it works: you are probably either an android or really, really, really high.

I am both sorry and not sorry.

If you are concerned that you may be mechanically inclined, that’s natural. Just watch today’s Mind Control Double Feature and all your worries will be replaced by other, deeper, more insidious worries. For today we explore the circuits of our mind. Today we scrape the solder off our cerebellums. Are we robots? Are we not men? We are unsure. We may be Devo.

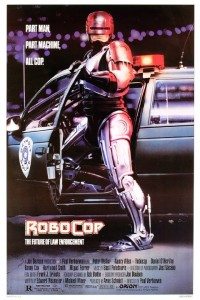

RoboCop (1987)

The future of law enforcement is here, and it will probably both kill you and be you. You are the drone that will blast your own upgraded body from the ruins of your overcrowded, corrupt, corporate-controlled city.

The future of law enforcement is here, and it will probably both kill you and be you. You are the drone that will blast your own upgraded body from the ruins of your overcrowded, corrupt, corporate-controlled city.

Hooray!

Yes, they have remade this film and no, I have not seen the remake of RoboCop. I do not need to see it to know that it would be near impossible to improve on Paul Verhoeven’s original. Verhoeven is a master of composing blockbuster entertainments from subversive elements. His films—like Starship Troopers and Total Recall and even earlier works like The Fourth Man—are exciting, disturbing, funny, and full of crowd-pleasing violence, sex, and meaning. That’s right: I said meaning! Maybe you know what that means?

While most audiences will simply roll along with Verhoeven’s films without considering their underlying themes, those themes are inextricably linked with all the glorious action. That is what makes RoboCop a masterpiece of modern cinema.

In RoboCop, massive corporation OCP sits above the stinking husk of Detroit like a carrion bird. The firm takes over the police force as part of its scheme to rebuild swaths of the city into its own sewn up fiefdom. The police aren’t so keen on this, so OCP develops a method of control that’s more controllable.

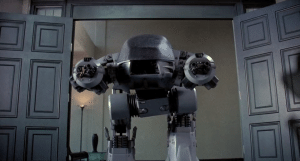

Senior OCP President Dick Jones (Ronny Cox) has a prototype sentry robot, the ED-209, which his team has built—but, to put it mildly, it displays flaws. Young turk Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer) takes Jones’ setback as an opportunity to convince the ‘old man’—OCP Chairman (Dan O’Herlihy)—to give his RoboCop program a shot. And ‘a shot’ is definitely the correct idiom, as RoboCop will be an android and that requires a still-living but no longer viable human body. Where to get such an item on the cheap? How about if we transfer less experienced cops to extremely dangerous districts and hope for almost but not quite the worst?

This layer of RoboCop—of which I’ve only described a scene or two—tells a cutthroat tale of voracious corporate callousness, witnessed from the top down. It may or may not be about human beings.

In contrast, we get the inner layer of RoboCop‘s onion. Officer Alex Murphy (Peter Weller) has won a lifetime stint as a paranoid android, but that’s news to him. He gets shunted to the shit, paired with veteran officer Anne Lewis (Nancy Allen), and you might suspect where this is heading. Enter Kurtwood Smith as Clarence Boddicker, Ray Wise as Leon Nash, and other unseemly gentlemen of debatable humanity, who link the two stories and, in doing so, risk their existence in our post-human future.

RoboCop revolves around whether technology can separate us from our species or whether that technology is nothing but a rough-hewn flint ax in the hands of fools. RoboCop suggests that what’s actually inhumane lurks right inside your denuded skull.

Are you human? Are you alive in there? What’s your name?

Your name is Murphy.

RoboCop is a violent, gross, hysterical, essential film. It is the sort of movie that will never grow old, because its appeal and intellect are not based upon passing trends or the latest effects technology. The film finds secure footing in its exceptionally strong cast, maneuvering them through shockingly raw material. RoboCop pulls no punches. It is about nothing less than humanity’s struggle for survival against our own worst enemy: ourselves.

It is a struggle I suspect we may not survive. I am both sorry and not sorry.

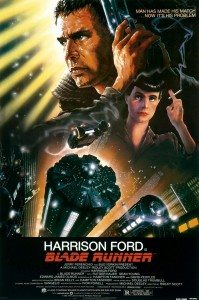

Blade Runner (1982)

Now that RoboCop has pummeled you with the need to retain your humanity, Blade Runner will play devil’s advocate. Maybe being human isn’t all it’s cracked up to be?

Now that RoboCop has pummeled you with the need to retain your humanity, Blade Runner will play devil’s advocate. Maybe being human isn’t all it’s cracked up to be?

Maybe, now that I think on it, it’s the robots who are the only real humans? Or maybe all the real humans are robots?

If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes.

Most of you will have seen Blade Runner in one form or another, but you should really consider watching it again, right now, after watching RoboCop.

There is an awful lot to say about this film, but I’ll keep it brief.

First; the picture finds its provenance in a Philp K. Dick book, “Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep”. The book is significantly different from the film and equally excellent. Reading it before or after watching Blade Runner will only enhance the experience of the film. Do not concern yourself with avoiding spoilers, because films this good cannot be spoiled. Second; do yourself an immense favor and only consider watching ‘The Director’s Cut’ or ‘The Final Cut’ versions of Blade Runner, which are too similar to each other for me to easily distinguish. Both do away with the treacly crap the studio burdened the theatrical release with—an insulting voice over, a tacked-on ending, and some ill-considered cuts.

Blade Runner pursues the inhuman through a dystopian future Los Angeles (2019 is coming up fast, kids) alongside Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford). Deckard is a ‘blade runner’, one of the cops tasked with corralling robots who illegally come to Earth. These ‘replicants’, unlike the machine men in RoboCop, are distinguishable from humans in only three ways. The first is through a complicated, lengthy Voight-Kampff test which exposes their slight lack of empathic response; the second is through their abbreviated lifespans; and the third is in their superhuman abilities, which may include strength, speed, and intelligence.

Blade Runner pursues the inhuman through a dystopian future Los Angeles (2019 is coming up fast, kids) alongside Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford). Deckard is a ‘blade runner’, one of the cops tasked with corralling robots who illegally come to Earth. These ‘replicants’, unlike the machine men in RoboCop, are distinguishable from humans in only three ways. The first is through a complicated, lengthy Voight-Kampff test which exposes their slight lack of empathic response; the second is through their abbreviated lifespans; and the third is in their superhuman abilities, which may include strength, speed, and intelligence.

Basically, they’re you, just better. So better kill them. We can’t let anything without empathy live, after all. That’s what it means to have empathy, right?

To be empathic is human. If you feel me, you must be human, so let the slaughter commence. Bring in ED-209.

Like RoboCop, it’s easy to watch Blade Runner enrapt in its surface level appeal. This is a sci-fi action thriller that looks as ruinously beautiful as L.A. might never be. Ridley Scott‘s direction is stellar enough to forgive most everything else he’s made since. Its production design is so iconic it’ll reveal the flaws in all your favorite films. On top of Harrison Ford’s shadowy turn as Rick Deckard, you’ve got M. Emmet Walsh, Rutger Hauer, Darryl Hannah, Sean Young, Edward James Olmos, Joanna Cassidy, Brion James, William Sanderson, and Joe Turkel—all excellent, even Sean Young, although most of that may be adept casting. If you haven’t heard Vangelis’ soundtrack to Blade Runner, it’s a score that kept me sane when I was locked in Los Angeles traffic for a month.

Like RoboCop, it’s easy to watch Blade Runner enrapt in its surface level appeal. This is a sci-fi action thriller that looks as ruinously beautiful as L.A. might never be. Ridley Scott‘s direction is stellar enough to forgive most everything else he’s made since. Its production design is so iconic it’ll reveal the flaws in all your favorite films. On top of Harrison Ford’s shadowy turn as Rick Deckard, you’ve got M. Emmet Walsh, Rutger Hauer, Darryl Hannah, Sean Young, Edward James Olmos, Joanna Cassidy, Brion James, William Sanderson, and Joe Turkel—all excellent, even Sean Young, although most of that may be adept casting. If you haven’t heard Vangelis’ soundtrack to Blade Runner, it’s a score that kept me sane when I was locked in Los Angeles traffic for a month.

Beneath this intoxicating mixture of sight and sound, Blade Runner, like RoboCop, gets its hands dirty questioning our humanity. Nothing is left at face value in this film. That’s the genius of Philip K. Dick, whose ideas power Hampton Fancher and David Peoples‘ brilliant script. Dick makes the molars that gnaw through our calcified assumptions, exposing the rich marrow inside. The questions he asks in his stories—stories like “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” which is the basis for Total Recall—are almost too big to contain. Whether you read them or see them adapted for the screen, you have little choice but to bring the ideas home with you so you can continue to try to digest them over the following days.

Beneath this intoxicating mixture of sight and sound, Blade Runner, like RoboCop, gets its hands dirty questioning our humanity. Nothing is left at face value in this film. That’s the genius of Philip K. Dick, whose ideas power Hampton Fancher and David Peoples‘ brilliant script. Dick makes the molars that gnaw through our calcified assumptions, exposing the rich marrow inside. The questions he asks in his stories—stories like “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” which is the basis for Total Recall—are almost too big to contain. Whether you read them or see them adapted for the screen, you have little choice but to bring the ideas home with you so you can continue to try to digest them over the following days.

Good luck!

In Blade Runner, lines of dialogue, sequences of events, and even props seen in passing will expose entire seams of intellectual ore. All you need to do is watch, and think, and—if you’re capable—have empathy.

Watch Blade Runner. See Deckard hunt down his own humanity. In the end, try to tell: will he be man or machine?

How could one possibly tell the difference?