I understand many things. I know what lurks in the hearts of men. I know why the caged bird sings. I can even discern, via scientific method, how many licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie-Pop. But I have no idea why someone would make a film like Breathe In.

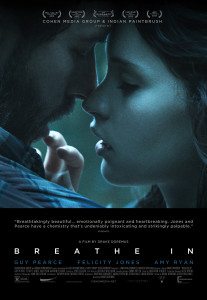

Breathe In, a film co-‘written’ and directed by Drake Doremus, was a film I fought the urge to walk out of from the moment it began. It is a film in which I found myself studying the walls of the theater rather than watch the screen. Well-acted and competently shot, it bravely takes a clichéd tale of infidelity and does nothing new or interesting with it.

Breathe In, a film co-‘written’ and directed by Drake Doremus, was a film I fought the urge to walk out of from the moment it began. It is a film in which I found myself studying the walls of the theater rather than watch the screen. Well-acted and competently shot, it bravely takes a clichéd tale of infidelity and does nothing new or interesting with it.

Allow me to introduce you to the film’s premise. Guy Pierce plays high school music teacher Keith Reynolds, a man who pines for his wild, rock band days and a home in Manhattan. His wife, Megan (Amy Ryan), sells—and I’m not kidding—cookie jars for a living. Together with their 18-year old daughter Lauren (Mackenzie Davis), they live in some grand home an hour out of New York City. Into their world comes Sophie (Felicity Jones), an impossibly nubile and talented exchange student.

Guess what happens.

Breathe In is an improvised picture, in which Doremus and co-‘writer’ Ben York Jones outlined the scenes in detail and then allowed their cast to workshop the dialogue until they had the nuggets of truth they sought.

As Doremus said to The Guardian:

I start with a 60-page outline that basically reads like a short story, filled with backstory, the emotional beats of the scene, subtext, plot points, but very little dialogue. … Every take, the scene gets more and more distilled. The first take is 15 minutes, the second take is 10, and before you know it we get down to the two-minute scene we need.

So he writes a short story of questionable value then forces his actors—individuals not known for their writing ability by and large—to condense his ideas into scenes which are simultaneously plodding and abbreviated.

To be kind, I will begin with the film’s strong points, of which I found two. Guy Pierce and Felicity Jones kept me from laughing at the preposterousness of their characters despite the eye-rolling situations those characters worked themselves into. That’s one good thing. The second is that Kyle MacLachlan, who is in the film for one scene, seems to have mysteriously matured into Martin Sheen. That was both curious and amusing.

To be kind, I will begin with the film’s strong points, of which I found two. Guy Pierce and Felicity Jones kept me from laughing at the preposterousness of their characters despite the eye-rolling situations those characters worked themselves into. That’s one good thing. The second is that Kyle MacLachlan, who is in the film for one scene, seems to have mysteriously matured into Martin Sheen. That was both curious and amusing.

As for the rest of the film: why? Why would you bother outlining, let alone filming, another story of a married man who falls for his much-too-young charge? If you did so, certainly you’d have to have something new to add — that would be any audience member’s assumption. As the film ended and my incredulity failed to fade, however, I wracked my brain: what is a viewer meant to gain from watching Breathe In?

Is there, perhaps, a moral lesson here for the insipid among us? For example: Do not get married to a woman who denigrates your passions in favor of reselling cookie jars? Or, alternately: Do not succumb to the temptation of a girl who looks too young to be your daughter and then fail to consider any of the implications of running away with her? And by ‘any’ I mean ANY. Pierce’s character’s forethought covers packing up an armload of flannel shirts. With these and his rogue exchange student, he intends to make a new life. Flannel shirts: check. Eighteen-year old girl on a student visa: check. Let’s go.

Is there, perhaps, a moral lesson here for the insipid among us? For example: Do not get married to a woman who denigrates your passions in favor of reselling cookie jars? Or, alternately: Do not succumb to the temptation of a girl who looks too young to be your daughter and then fail to consider any of the implications of running away with her? And by ‘any’ I mean ANY. Pierce’s character’s forethought covers packing up an armload of flannel shirts. With these and his rogue exchange student, he intends to make a new life. Flannel shirts: check. Eighteen-year old girl on a student visa: check. Let’s go.

If a man was indeed that insane and impractical, surely those characteristics would show in other areas of his life. But they don’t. Keith Reynolds is the sort of bloke who longingly looks at photos of himself as a younger man on stage, playing rock guitar. From this we know he pines for the past. It is very subtle. He is the sort of man who steals away with his lolita to a nice public place for a bit of canoodling. From this we know he is in a stupid movie. It is very subtle.

Or perhaps there is another, more emotional, sort of meaning to Breathe In. We are meant to watch it and drift in thrall to its characters. We are meant to identify with either the suffocating Keith or the wide-eyed Sophie, and know of the world and ourselves from their experiences. I would posit that if you attend movies ever and still have something to learn from either of these idiots’ experiences, then you have a learning disability. Certainly we are not meant to congeal with Amy Ryan’s harridan character. She sells cookie jars. She stays to drive the entire swim team home in shifts even though the family—all at the swim meet—has brought two cars. Have none of the other parents come to cheer on their offspring? Who’s writing this film? Oh yes. The actors.

Or perhaps there is another, more emotional, sort of meaning to Breathe In. We are meant to watch it and drift in thrall to its characters. We are meant to identify with either the suffocating Keith or the wide-eyed Sophie, and know of the world and ourselves from their experiences. I would posit that if you attend movies ever and still have something to learn from either of these idiots’ experiences, then you have a learning disability. Certainly we are not meant to congeal with Amy Ryan’s harridan character. She sells cookie jars. She stays to drive the entire swim team home in shifts even though the family—all at the swim meet—has brought two cars. Have none of the other parents come to cheer on their offspring? Who’s writing this film? Oh yes. The actors.

As for Mackenzie Davis’ Lauren, I’m just sorry. She is a character that combines the greatest hits from every after-school special I’ve ever had the pleasure not to see. Davis does as well as possible, but Lauren is the second tier plot line about which no one—not even her parents—cares. As long as she shows up for their annual ‘end of summer’ photo which both starts and ends Breathe In, she is free to cease existing the rest of the time. Is it a spoiler to tell you that she attempts to cease existing? I suppose it might be, if you’re the type who becomes enrapt in scenes of forbidden romance to the point that you can’t project where a story is sure to go.

Breathe In takes its title from a moment shared between Sophie and Keith. Keith is stressing about his audition for a chair at the symphony. Sophie teaches him a relaxation technique. It’s complicated: you must close your eyes and breathe. So maybe that’s it. This is a film about relaxing.

Relax into infidelity with a girl too young to share a beer with. Relax into ruining your life. Relax, because at the end of the year, you’ll take another family photo, and nothing will be the same regardless of what you do or don’t do. Relax. You can always buy more cookie jars. The markup on those is unbelievable.