Is there anything more charming and delightful than filthy rich con-artists stealing from each other? Back in the Depression—no, not the one you’re suffering through now, not the one a few years back, not that time in the late ‘80s nor the the latter half of the ‘70s, and not that time you lived in a barrel reciting anti-war poetry with odiferous beatniks in the ‘50s–the actual Depression, the Great one (and boy was it ever! what a blast!), the one that lasted over a decade, the one we needed a world war to pull us out of, back then, no, nothing was more delightful than watching impossibly rich ne’er-do-wells robbing even richer ones only to fall madly in love with one another and sail away into diamond encrusted sunsets.

These days, the rich are slightly less amusing. Might have something to do with robbing the poor instead of each other.

Which is why for this week’s Mind Control Double Feature we take a journey backwards in time to an era when, like Mia Farrow in The Purple Rose of Cairo, we would huddle in movie palaces dreaming of a world so very close, yet so very far out of reach.

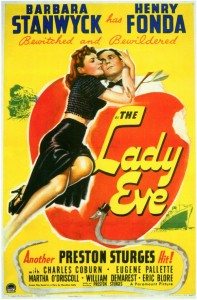

The Lady Eve (1941)

Writer/director Preston Sturges had one hell of a run in the early ‘40s. The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek is a Mind Control favorite, as is Sullivan’s Travels. Another is The Lady Eve, Sturges’s take on the Hollywood romantic comedy. Which take marked the pinnacle of the genre at least until Annie Hall.

Barbara Stanwyck, renowned around Mind Control as a woman who gets what she wants, plays street-smart con-artist Jean Harrington. Abetted by her criminal father and his partner, they set out to take Amazonian explorer and snake expert, Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), for everything he’s got. Which is a lot. He’s the heir to the Pike Ale fortune.

Pike is no match for Jean’s wily womanly wiles. He falls for her like a bucket of snakes. But alas—before she’s done anything but seduce him, her nefarious scheme is discovered! Pike dumps her just in time.

Jean doesn’t take kindly to being bested. She’s got an axe to grind with Pike. Or as she famously puts it, “I need him like the axe needs the turkey.” Sturges had a way with words, didn’t he? And romance. Like that between a turkey and an axe.

Jean, calling herself Eve, goes after Pike again, and for reasons known only to the romantic comedy gods above, he doesn’t see through her feeble disguise. Instead he marvels at how very much she resembles Jean, falls in love with her, and generally falls down a lot when she’s around, the poor, love-struck klutz.

Get it? He falls a lot? And he’s a snake expert? Eve. Temptation. The Fall. That’s right, it’s a religious picture.

Jean wants him to fall in love with her. She wants him to marry her. She’s got a plan. But will it work? Will she fleece this poor sap for everything he’s got? Or will she—wait for it—fall in love with her darling turkey?

I’m not going to claim that Sturges keeps you guessing on that count, but he is a man possessed of a weird and funny imagination. He’ll keep you entertained. Few filmmakers wrote snappier dialogue than Sturges. His movies are obviously not factory produced Hollywood confections. They come from one mind, a mind set on poking holes in everything one might hold sacred.

In The Lady Eve, Sturges allows you to escape into the dreamy Hollywood world of the rich and carefree, but he makes sure you know that he knows just how absurd a world that is.

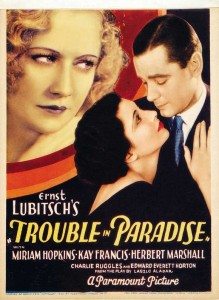

Trouble In Paradise (1932)

Back in time further still, into the pre-code era, when Hollywood’s moral standards were famously lax. Well. I suppose they’ve always been famously lax, but in the early ‘30s, Hollywood wasn’t even pretending otherwise. Movie houses were chock full of sex and violence.

Into this world came director Ernst Lubitsch, who’d been making movies in Hollywood since he arrived from Germany in the ‘20s. He’s best known for a string of movies made between ’39 and ’42, Ninotchka, The Shop Around The Corner, To Be Or Not To Be, and Heaven Can Wait. But we’re here to appreciate the twisted, amoral glory that is Trouble In Paradise.

It tells a tale as old as time. Lily and Gaston (Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins) are each master thieves masquerading as nobility. They run in the circles of the rich and famous, and rob them, gleefully. After discovering the truth about one another (by trading ever wittier barbs, of course), they fall in love and team up, embarking on a grand scheme to rob Madame Colet (Kay Francis), a rich perfume manufacturer.

A rich perfume manufacturer? Sounds hot. Gaston gets a job working for her. She falls for him. Does he fall for her? Lily thinks so. And she is not amused. It’s the classic romantic triangle, two cons and a mark. Trouble ensues. In paradise.

Looks like this too is a religious picture. We start out with Eve and end up in Eden. Needless to say, many figurative apples are eaten.

Speaking of which, the sexual innuendo in here is intense. The movie was pulled from distribution in ’35 for being too racy. It wasn’t seen again until ’68. One famous exchange between Gaston and Colet:

Madame Colet, if I were your father, which fortunately I am not, and you made any attempt to handle your own business affairs, I would give you a good spanking – in a business way, of course.

What would you do if you were my secretary?

The same thing.

You’re hired.

It’s a movie set in the same world all of Lubitsch’s movies are set in: Lubitschland. Peopled by impossibly rich dandies and sultry, jewel bedraped ladies, with scenes in Venice, in grand hotels, at lavish cocktails parties, everyone smoking and drinking martinis like tap water, does anyone in this movie have a real job? They’re all wonderfully witty, dressed to the nines, and having more sex in 83 minutes of movie time than you will in your entire life.

Trouble In Paradise isn’t as nutty as The Lady Eve. Lubitsch didn’t make screwball comedies. The characters here are almost, but not quite, real people. There’s something a little sad about them, underneath the knowing wisecracks and clever thefts. It’s a sadness they recognize, but choose to ignore. They’d rather have a good time.

Ahhh! Them not so good yet not so bad ol’ times! I read your comparison of the two flicks with much interest and maybe also a bit of inside knowledge, one for being a lifelong German cinema geek and second for being PA to a person who actually lives like Lubitschpeople in real life. The interesting thing about Lubitschland and Lubitschpeople appears to me, that as you mentioned so perfectly well, they are almost real but not quite … The same applies to nowadays oligarchs and their cliques. They believe to live a real life, but they themselves make sure it does not get the stench of completely real. They want to remain in some sort of controlled dream, wrapped in the illusion that they are exercising free will … well you get what I mean.

Another interesting remark of yours was that these films all dealt with being rich as opposed to normal, real people. I guess cinema has not changed that much after all. The movies that always appealed to the great majorities were films about minorities and with preference rich and exotic ones. This has not changed a bit. Films about ordinary people might be great art sometimes and get their awards and rewards, but ultimately, if moviegoers’ bellies are asked, they prefer the glitz world on celluloid or digital film nowadays. It is sad but let’s not kid us about this. And then, there are the Oscars which obviously try to replicate some of that famed rich and luxurious life and its appeal to the human ants …

I think people have always enjoyed most movies that show a side of life unknown to them. In the old days of these two movies, that life was absolutely one of the rich and carefree, larking about, having a grand time.

Even in eras like the ’70s, the gritty realism showed people not the lives they were leading, but those of fucked up anti-heroes. Movie escape can be into worlds you wish you could be a part of as much as worlds you fear to encounter.

And yes, as for the Oscars and such, Hollywood is America’s version of royalty.