The problem with physics these days, and for maybe a good hundred years now, is that it deals with things so small and theoretical—the smallest ‘particles’ making up the fabric of the universe—that to anyone without a PhD in the subject, it’s almost impossible to understand. I have a minor obsession with physics and read every popular book on the subject I can get my hands on, and I find half of it only comprehensible in the most general, metaphorical sense (higher math is not my strong suit). Hell, even physics genius Richard Feynman famously said, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” And he’s the guy who invented the equations describing quantum behavior.

The problem isn’t for the actual physicists. They’re happy to delve deep into their highly specialized theories and experiments. The problem is for the public at large. Electricity, radio, cars, airplanes, microwave ovens, atomic bombs—such things are easy for people to get excited about. They’re easy to comprehend, on a general level.

Particle physics is not easy to comprehend on any level. And even if you did understand the subatomic world (in the theoretical way in which it’s currently understood), what good does that do you? What does finding a new particle provide us on a practical level? No one knows. Which is fine by physicists. They understand that pure knowledge comes first, and practical applications come later. Regular folks aren’t often as interested in knowing something purely for the sake of knowing it, especially when that knowledge will affect their lives not at all.

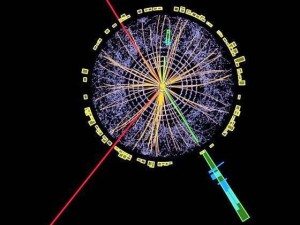

The new documentary Particle Fever, directed by theoretical physicist Mark Levinson, strives to paint physicists as relatable people with relatable passions while telling the story of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) project in Switzerland, and its use in proving the existence of the previously theoretical Higgs boson, unfortunately dubbed “the God particle” by the media.

The film covers four years from ’08 to ’12, and includes interviews, self-recordings, and plenty of footage taken at the LHC during its initial runs. It’s edited by cinema wizard Walter Murch (of Apocalypse Now, among others, fame), so it’s certainly a well-edited, well-paced movie.

Its biggest success is in communicating just how excited and passionate physicists are at the notion of finding the Higgs boson. When at the end its existence is finally confirmed (not a spoiler; surely you keep up with the NYT science section?), you want to stand up and cheer along with the cheering physicists, you want to hug Peter Higgs himself, who’s there in the auditorium to hear the announcement, who wipes a tear from his eye.

The movie is less successful at communicating why finding the Higgs boson is so important that the world’s scientific community spent 20 years and vast sums of money to build the LHC, the largest machine in the history of the world, in the hope of finding it. The personable physicists the movie focuses on give us the basic explanation: the Higgs boson is the final undiscovered piece of the sub-atomic model physicists have been using for many years. If it exists, the model will be proven correct. If not, physics will unravel. More specifically, if the Higgs is found, its weight will determine which theoretical models of physics are more likely correct and should be pursued, and which should be discarded. A big deal, then.

There’s one revealing conversation between two older physicists, one of whom fears that his past 40 years of studying and teaching will have been a waste of time should a new truth be revealed. He’s deeply troubled by the notion. For these physicists, the real world effect of finding the Higgs is indeed profound.

Yet even with all of that, the actual science is so briefly sketched as to not be present. We’re left to take the scientists’ word that finding the Higgs changes everything. Then they find it. Is everything changed? I don’t know. I feel about the same.

Curiously, the weight of the newly discovered Higgs boson turns out to be right in the middle of the two predicted extremes. Which means it neither disproves nor confirms the two primary competing theories about the nature of the universe (simplified in the movie as the supersymmetry theory and the multiverse theory). Instead, it shows that either of these theories (or any number of variations) could still wind up being correct. In other words, this is great news for physicists–they weren’t wrong! The Higgs does exist, the standard model is correct, and because of its size, many avenues of exploration are wide open. Which still doesn’t make me feel much like the world has changed. At least the physicists are cheering.

So, the end result here is that while the movie communicates the excitement and passion of the physicists—you get it, it’s infectious, they’re cool, they say “fuck” a lot—it doesn’t go deep into the why. Yes, it’s all about truth! Knowledge! The mysteries of the universe laid open! It’s just that it’s not a movie about those mysteries. It’s about finding the thing that will aid in solving the mysteries, one day down the road.

I have to admit, at times I felt like Particle Fever was an unusually excellent version of something you’d show high school kids in an attempt to prove that “No, really, you guys! Science is awesome! Yeah!” A viewer with little knowledge of the world of physics isn’t going to come out having any idea why the discovery of the Higgs matters, aside from its making a lot of physicists very happy.

Which is something. Clearly, our world suffers from the perception that scientists are evil brainiacs out to blow up the world. (The movie recalls the media reporting that “some scientists” (i.e. loons looking for airtime) believed switching on the LHC would result in a black hole forming and swallowing the earth.) Any movie that shows scientists in this kind of real-world, positive light has something going for it. As to the ultimate significance of the Higgs boson, we’ll have to wait for the sequel to find out why everything we know is wrong.

Which makes me think that you might wish to prepare a Multiple Feture post devoted to mad scientists in films. I might add some strange ones.

oops, make that “Feature” please!

It’s a rare movie where a scientist isn’t mad. Because after all, the mad ones are where the drama is. But yes, there’s certainly a lot to be written about the history of cinematic mad scientists. Hmm…

we do sort of have one along that vein. a few actually, but i was thinking of It’s Alive!