Deep in the un-past—nestling in cotton batting, enclosed in a box, wrapped in tissue, and tied with ribbon—rests the welcome memory of The Grand Budapest Hotel. It is a gift of nostalgia for what has never been. It is a ticket to the world Wes Anderson has whittled from the wider universe. It is a delightful confection and his best film since Rushmore.

In The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson finally steps fully clear of reality. He goes so Wes Anderson that he emerges clear out the other side, into a place past twee and quirky. That place is called fantasy and the result is reasonably fantastic.

In Bottle Rocket and Rushmore, Anderson took a recognizably normal world and added a single character (Dignan; Max Fischer) to distort the gravity of the films. Like a black hole, Dignan and Max warped and perverted their surroundings, forcing their universes to conform to their alternate perspectives. Since those films, Wes Anderson has continually turned up the volume on the distortion. In The Royal Tenenbaums, it was an entire strange family. Then the whole world may have been recognizably ours—just as Max Fischer may have been recognizably human—but it all remained too off-kilter to be even momentarily believed. Characters, situations, relationships all seemed staged, because they were staged. So very, meticulously staged.

Many people love these later Anderson films, but I’m not one of them. I find little to hold on to in their stories; no one in them to recognize as a strange sort of me. And I’m plenty strange to begin with.

In The Grand Budapest Hotel, it’s different. We only start off in Anderson’s off-kilter world, in a European cemetery that holds a monument to a great writer. A girl reads a book and we see the book’s author (Tom Wilkinson) explaining the story it contains. This is one of the film’s best scenes, and it is only the tissue paper around the box with the batting that holds the confection.

Anderson lures us from our world, in stages, into a world that never was, each step relieving the audience of more and more attachment without sacrificing their investment. By the time we’ve left Wilkinson, and then Jude Law and F. Murray Abraham and Jason Schwartzman, to reach the final heyday of The Grand Budapest, we are so far removed from anything that has ever been real, we are liberated. Anderson manages—finally—to coax us into a world purely of his own imagining. He doesn’t even feel obliged to pronounce ‘Budapest’ correctly, or set a hotel named for Hungary’s capital in Hungary. What matters reality? We are on vacation in Anderson’s skull.

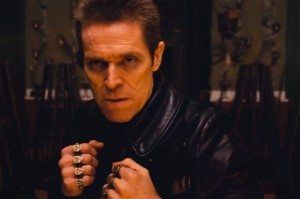

The Grand Budapest Hotel is funny. It is out-sized and exaggerated and—although a bit indulgent by the end—exceptionally enjoyable. Watching it I felt no need to conform Wes Anderson’s miniaturized, highly detailed quaintness to anything that existed outside of the film. Within the construct of the Hotel’s world, it all worked and in frequently surprising ways. Ralph Fiennes is fantastic, particularly his outbursts of profanity. Willem Dafoe gets the best one-note role this side of Neo in The Matrix. The look of the film—so Wes Anderson it felt entirely like one of Max Fischer’s plays from Rushmore—is mysteriously ingratiating and believable, like Cary Grant’s fabricated accent.

Don’t you remember how the world used to be? Back before the war in the Andersonian age? When one could book a suite in The Grand Budapest Hotel and expect only the most civilized treatment give or take the loss of a few fingers?

That is the magic of Wes Anderson’s latest film. He makes you nostalgic for something that never was. He makes this confectionary treat—hand made at Mendl’s—look so very delicious, even though you can plainly see it is little but sugar mixed with color and air.

I think I might go see it again.