The Grand Budapest Hotel is not set in Hungary. It’s set in the imaginary European Republic of Zubrowka. More exactly, it’s set in the little dollhouse of Wes Anderson’s head. People are calling this film the most Wes Andersonesque of all Wes Anderson movies. They said that of his last film, too, Moonrise Kingdom. I’m sure they said it of The Life Aquatic and The Fantastic Mr. Fox as well. I think we can agree that Anderson has a unique aesthetic, and that in The Grand Budapest Hotel, as in so many of his other films, it is on full display.

I liked The Grand Budapest Hotel quite a bit. It is, on the whole, delightful. A word one has no choice but to use when describing it. Anderson delights in being delightful. It is his raison d’etre. I feared I wouldn’t like it. I did not like Moonrise Kingdom, which felt entirely fake to me, despite clearly wanting me to care about and believe in the many relationships it detailed. I agreed that it was Anderdon at his most Andersonesque—in the worst way possible. It felt like he’d plunged into his world of miniature toys and dolls, never to emerge.

Rushmore remains his masterpiece. Thinking about it compared to Moonrise Kingdom (as I did when seeing the latter), I felt like the problem with his later movies lies in how every characters is as idiosyncratic as Max. The other characters in Rushmore, though some are certainly a bit off-kilter, might easily exist in the real world. They react to Max’s oddness like a real person would. Furthermore, Max’s story is told through Max’s eyes, and in his plays we see how he sees the world: as a stage full of outrageous drama, passion, love, hate, and redemption. The movie Rushmore unfolds as one of Max’s plays. It’s all of a piece. And in the end, it’s geniunely emotional and real. Anderson has never made another movie with an ending as simple and powerful as Rushmore’s.

Moonrise Kingdom, on the other hand, is peopled solely by extreme versions of Max, every one of them wackier than the next. There’s no one to care about. It feels like watching animatronic dolls put through their motions. The same could be said (by me, anyway) of The Darjeeling Limited and The Life Aquatic. Fake and mannered in the extreme, with nothing to connect to aside from the lovely production design.

Since Rushmore, the Anderson movie I’ve liked the most is The Fantastic Mr. Fox (and it’s a mild liking; Grand Budapest is far superior). Anderson’s style set in animation, in stop-motion, no less, seemed a perfect fit, as though he’d been building up to that all along, able at last to dispense with actors and move his little game pieces around to his precise specifications. Which loosened him up, in a sense, humor and story-wise. Might have helped that he was working from a Roald Dahl book.

Reading comments on movie blog reviews (not a recommended practice (aside, naturally, from those found on this movie blog)), I find it interesting that even among fans of Anderson’s work, nobody agrees on which are his best and worst movies. Pick any combination, and somebody will argue vehemently for them. Some people love all of his movies except Mr. Fox. Some love only Mr. Fox. Some love Darjeeling and are lukewarm on Rushmore. Some think Tennenbaums is better than all the rest. Many love Moonrise, while others (like me) found it twee and annoying.

I think this is rather curious. Not many idiosyncratic directors have such polarized opinions on their work, especially among their most ardent fans. I’ve never heard a Kubrick fan say 2001 was over-rated. Or a Herzog fan shrug off Aguirre, The Wrath of God. Or a Woody Allen fan disparage Annie Hall. Or a Spike Jonze fan speak ill of Being John Malkovich.

I expect The Grand Budapest Hotel will be no different. I think it works because it makes no attempt to be anything more than a funny and profane and slightly wistful cartoon. Others may find such an aesthetic off-putting. But to hell with them. Unlike in Moonrise Kingdom, the relationships and passions Anderson asks us to believe in in The Grand Budapest are completely plausible. They’re exaggerated for comic effect, they’re told with simple brushstrokes–and they work.

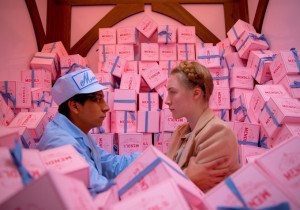

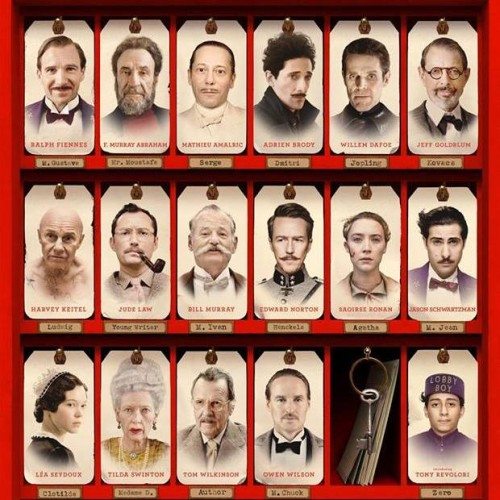

The central relationship is between master concierge Gustave H. (an excellent Ralph Fiennes) and his new lobby boy, Zero (newcomer Tony Revolori, also excellent). Zero is dedicated in a way Gustave instantly appreciates. Their bond, however quickly established, is in the context of the cartoon perfectly real. Beyond that, the only emotional bond is between Zero and his girlfriend, Agatha (Saoirse Ronan), whose relationship ends so off-handedly maybe you didn’t need to feel so deeply about it anyhow. But you do. Which is nice.

The story is essentially a mystery. Madame D. (Tilda Swinton), a woman terribly old and rich, dies. An habitué of The Grand Budapest, she had a long-standing romance with Gustave, who in fact romances every rich old woman who stays at the hotel. Her complicated will bestows upon Gustave the priceless painting “Boy With Apple.” Her evil son, Dmitri (Adrien Brody), it outraged. Gustave nabs the painting before the will can be disputed, but in short order is accused of having poisoned Madame D., and finds himself in jail.

Escapes and adventures multitudinous follow. Chase scenes are shot in simple stop-motion. Countryside vistas are presented as obviously two-dimensional paintings. Anderson understands one thing very well, something I wish other filmmakers did too: CGI is but one of many tools to create imagined worlds. It’s no more real than any other. It’s a stylistic choice. That everyone uses the same choice is one reason so many movies are so similarly boring.

Anderson’s special effects are, well, what can I say? They’re delightful. They’re charming. They’re part of the cartoon. The movie is centered around a grand hotel on a mountaintop? You know going in there will be a funicular on display.

Another nice angle to this particular cartoon is Anderson’s unusual use of violence and profanity. Gustave is the most charming, suave concierge imaginable, but he’s also prone to frustration and saying of anything that tires him, “Oh, fuck it.” During a prison escape there’s an outrageously violent murder you wouldn’t expect in an Anderson film, nor any film played as a charming cartoon. These elements fit the story, which takes place as war comes to Zubrowka. A Nazi-like army (their symbol is a fanciful ZZ) is roaming the countryside. Tanks are massing. By the end, the Grand Budapest is turned into an army barracks. It’s a fading way of life, the one Gustave works so hard to maintain. It is suggested that even in Gustave’s time, the world he tries to inhabit has already passed him by.

This whole story is told at a remove of three levels. A girl reads a book, The Grand Budapest Hotel, on a park bench beside the bust of a deceased author. Back in time, the old author (Tom Wilkinson) relates how he came to hear the story he wrote in his book. Back further, and the young author (Jude Law) comes to stay at The Grand Budapest, now a run-down 1960s shadow of its former self, where he meets the old Zero (F. Murray Abraham), who relates the story of his lobby-boy adventures with Gustave H. To emphasize the different times, different sections of the movie are presented in aspect ratios to match their eras. Thus the bulk of the film is presented in an almost square image.

For its mood and style, Anderson took inspiration from the writings of Stefan Zweig, an Austrian whose novels, stories, and essays were very popular and influential in the ’20s and ’30s, who was known for conjuring (and yearning for) a Europe fast disappearing, and the films of early European immigrants such as Ernst Lubitsch. Although, on the whole, the style most on display is Anderson’s own.

If all of this sounds terribly precious, it most certainly is. But you knew that already. That’s Anderson’s thing, and he’s not going to stop doing it. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, he does it better than he has in ages. It’s my favorite Anderson movie since Rushmore. If you like cartoons, and old Europe, and hand-knitted special effects (so to speak), you will like this movie. Unless you don’t. With Anderson, one can never tell.

Thank you for another slightly surreal, sublimely snarky cinematic study/promenade. Your (and of course, Evil Genius’) excursions into movies pull me along with you; so wonderful are the conversational, humble-yet-irreverent absurdities of (most of) your insights that I, a wary rationalist–with no context other than your gourmands’ love for film and wordplay–skip gaily along behind you, a peripatetic Munchkin (in cinematic experience if not in stature) trailing after Dorothy and dog, Lollipop Guild forgotten.

More prosaically, I’m a student in a dual-degree professional program as well as a writer, and so chronically short on time. Your work feeds my deep hunger for a glimpse of culture outside the Lollipop Guild–er, the disciplines I study–and does so in short, refreshing bursts that don’t leave me feeling irresponsible for feeding the craving. (Feeding it so well, in fact, that I’ve read every single one of the posts on your 2013 ‘least read’ list…at the time they were posted.)

Thank you for your craft, and the humor and passion you bring to it; your reach is considerably broader (and on some days very much deeper) than you might think.

Aw, shucks. Thanks for your kind words. It’s a pleasure to know we have such a dedicated reader. Feel free to come on by and chat whenever the mood strikes…

No mention of the Bobcat cameo? Outrage and umbrage!

Bobcat was in Budapest? Where?!? Or was there an actual bobcat?