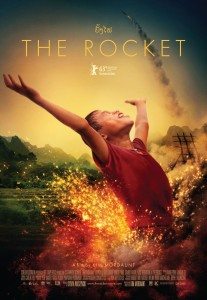

The Rocket—a new Laotian-language film from Australian writer/director Kim Mordaunt—is like one of those ill-considered dishes you get at over-eager Asian-fusion bistros.

The Rocket—a new Laotian-language film from Australian writer/director Kim Mordaunt—is like one of those ill-considered dishes you get at over-eager Asian-fusion bistros.

Picture a slice of chocolate cake sprinkled with crushed peanuts, chili flakes, bean sprouts, whole shrimp, and a nice glaze made from nam pla.

If that sounds perfect to you, then you will love The Rocket. Alas, I suspect if we put such a dessert on a menu, it would attract few takers. Some things just don’t blend. Western-style coming of age melodrama and Laotian culture might be two of those things.

Laos is a country that evokes strong memories in me. So, on the one hand, I fall squarely into the target market for a South East Asian tale like this. On the other hand, while I enjoy a bit of cake—even if it’s just metaphoric, melodramatic cake—I’m not the sort who wants to visit the Cheesecake Factory when I’m half-lost in foreign lands. That’s how The Rocket made me feel; as if I was forced to put what I had on one hand and on the other together, so that I ended up trying to clap Asian-infused chocolate cake.

The Rocket flaunts the natural beauty and stubborn poverty of Laos. The cultural personality of the country, too, crops up in ethnic costumes and in unexploded ordnance (which the United States left scattered across the country during its 1960’s Secret War). These elements get sprinkled over a confectionary fairy tale story—a story so typically Western it might as well take place in a suburb of Sydney or St. Louis.

The characters are Lao in appearance and in voice, but not in substance. Around them, Laos is just the beautiful and charged setting. It is framed as if in a Western film, because this is a Western film—not a Laotian one.

In The Rocket, Mali (Alice Keohavong) gives birth to twins, one stillborn. Her traditional mother-in-law, Taitok (Bunsri Yindi), insists the surviving child—Ahlo (eventually Sitthiphon Disamoe) be killed. Tribal tradition dictates that one of each pair of twins is bad luck, and you never know which one until too late. So better kill them both. Taitok relents, however, and thus our tale. Will Ahlo be the bad luck twin or the good luck twin?

Let me pause here for you to formulate your own guess. You might as well also formulate your own background for this dark tradition, as Mordaunt never explains why these people might hold such beliefs or why superstition might be more or less important than anything else that in The Rocket.

While Ahlo’s twin-ness theoretically drives the story, it is also completely superfluous. He’s a normal sort of boy. His foibles may be movie-dramatic, but they aren’t signifiers of some curse, because the curse of twins isn’t really part of the story. Neither are the problems of unexploded ordnance, or callous international development, or even rocket construction competitions, all of which parade through the tale in turn. These things—the colors of Laos—provide beats for an unimaginative story about a boy trying to prove himself. The causes, progress, and resolution of his personal drama all remain resolutely impersonal. As if—like I said—the film is trying to spice up a familiar dish with some foreign flavor that doesn’t belong.

While the actors perform reasonably—including Loungnam Kaosainam as Ahlo’s young friend Akia and Thep Phongam as the James Brown-obsessed Uncle Purple—they’re all in the wrong film. This story was written and directed by an Australian. It is an Australian’s idea of what a Laotian story might be.

While the actors perform reasonably—including Loungnam Kaosainam as Ahlo’s young friend Akia and Thep Phongam as the James Brown-obsessed Uncle Purple—they’re all in the wrong film. This story was written and directed by an Australian. It is an Australian’s idea of what a Laotian story might be.

That’s a shame as Laos is full of stories, and ones that we haven’t heard. Perhaps Mordaunt has his own Australian stories to tell, as well. Those, too, would be preferable to an interloper’s take on another’s culture.

The Rocket opens March 7th at Landmark’s Opera Plaza and Shattuck theaters.