Long ago, in the olden days of 1982, director Godfrey Reggio made one of my favorite movies, Koyaanisqatsi. Shot by Ron Fricke, with brilliant original music by Philip Glass (who at the time had yet to score the 937 movies he’s scored since), Koyaanisqatsi was and is one of the strangest movies ever to gain some modicum of fame. I’ve seen it so many times it’s as though every frame of it has been pasted onto the interior walls of my skull.

Reggio followed it up with two sequels over the years. Powaqqatsi (’88) is darker and weirder than its predecessor, focusing on the third world and how the first has corrupted it to their own ends. Glass’s score is full of percussion and other instrumentation not often found in his work. I’ve seen Powaqqatsi a number of times, yet still have trouble picturing it, as though its images are forever swimming around the deep waters of my brain, lurking just beyond the light.

Naqoyqatsi (’02) came next, with an exceptionally lush Glass score and a more direct theme: war and technology. For me, it’s less powerful than the first two. Its images are heavily computer-manipulated, which though thematically logical drains them of impact. Or so I find. Its message seems too straightforward, whereas the first two Qatsi films go deep and wide, allowing vast latitudes of interpretation. Not that you should skip Naqoyqatsi. It’s still more fascinating than most movies.

Reggio’s latest, Visitors, is something of a continuation of the Qatsi trilogy, but not so much that it earns a Hopi title. It is the Qatsiless Qatsi. It’s a much more even-keeled movie, slow and meditative throughout, shot in 4K digital, presented in black & white. Glass’s music reflects the pace. It’s soft and melodious, of a piece with his more recent output, albeit less dynamic. There are some slightly insistent passages, but for the most part Visitors maintains a calm, flowing mood.

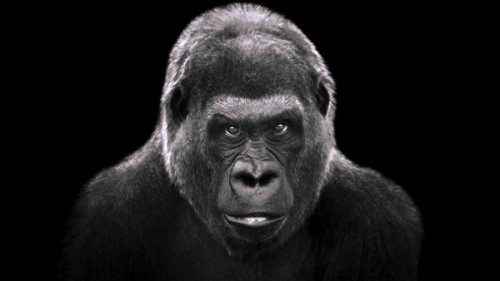

Visitors opens with a gorilla. She stares at us as we stare at her. It takes a moment to realize she’s being shown in slow-motion. Her eyes flick from side to side now and then. Her head moves incrementally. She’s shot against a digitally created black background. As her image fades away, we’re presented with what appear to be empty, deserted buildings, stretching up to the skies, across which clouds race. It’s a recurring image during the first third of the movie.

Reggio found the buildings in New Orleans. Reggio: “Those images have matured from images that looked like the chaos from the hurricane into images that looked like the ruins of modernity.”

Engraved into the stone of one building is the Latin phrase: NOVUS ORDO SECLORUM. Translated: New order of the ages. We then cut to a close-up of another engraving: VISITORS. Next come the faces.

People’s faces against a black background, one after the other, same as the gorilla. They too are shown in slow-motion. The camera ever so slowly pushes in. It’s just slow enough that you’re not sure it’s happening at first. It creates a floating, disorienting feeling. Stranger still is the feeling that the people on screen are watching you as intently as you’re watching them. At moments I wanted to step aside, out of their sightlines, and observe them watching the rest of the audience. These shots of people are intercut with the dead buildings and the clouds racing by. The meaning of which is…well. I don’t know. Are we the visitors? Are we metaphorically inside these buildings? Are we the new order of the ages? Or is the new order coming to replace us?

A later segment features close-ups of hands. The hands manipulate invisible objects, most readily identifiable: a computer mouse, a laptop, a smartphone, a piano. With the objects removed, the hands take on strange appearances. Spiders crawling over one another. Eyeless penguins pecking at a curious fish. A dancer’s legs.

A later segment features Louisiana swamps. The black & white looked to me like it was shot on infra-red film, with the green of the trees displaying as pure white. But of course Visitors wasn’t shot on film, so presumably this is a convenient trick of the computer. In any case, it looks beautiful and alien. The swamps are intercut with shots of deserted amusement park rollercoasters.

Unless those shots came before. Or after. The lulling effect of the movie has confused the order inside my mind. The other most memorable shot is of a group of people, in extreme slow-motion, watching—something. At first it’s hard to say what. A movie? Are they watching us? No, it’s not a movie. Maybe it’s a concert. One woman is raising her fist in the air. Finally a look builds on faces, rises, and explodes. Aha! A sporting event! Someone just scored! Or did something else important. It’s disorienting, to say the least.

The gorilla shows up two more times. The audience, that is, us, in the theater, we show up too, watching ourselves being watched by the gorilla.

I forgot the moon. The only stock footage in the piece, we see the moon’s surface rolling by, and eventually, the distant Earth rising behind it. Are we now watching ourselves watching ourselves being watched by the gorilla? Or are visitors observing us from afar?

I’m sure there will be reviews of this film, same as with Koyaanisqatsi, complaining of a simplistic message, in this case something about our computerized world, something about our culture of watching. But it’s not so simple. Or more to the point, it’s not so specific. Reggio makes movies to be experienced, to be felt. He creates a form from which every viewer creates their own meaning. “The subject of Visitors,” says Reggio, “is you watching the film.” Which is one of those statements that on the surface is simple and obvious, but the more you think about it, the more you’re forced to say, “Yes, obviously…but what does that mean?” No answer is provided.

Like the Qatsis, Visitors asks us to look at ourselves from an outside perspective. The sped-up and slowed-down footage in the first two Qatsis, the computer-manipulated images of Naqoyqatsi and Visitors, these tricks allow us to see the familiar in a new light. As though through the eyes of alien visitors. Maybe the visitors are the alien eyes through which we watch Visitors. Maybe this is a movie of our present seen as the distant past by watchers from a future world. Reggio describes the distancing effect of Visitors thus:

It’s creating a situation where a world we live in can actually start to speak to us. So how do we give the world a chance to speak to us is the modus operandi of the photography and the vision of the film. To give voice so the world can tell us something in a way we don’t have to see because it is so present, and it’s only normal that we can’t see what is most present to us.

Or then again, as he put it to one audience, “It’s like going to get a hamburger and there’s nothing in the bun except lettuce and tomato and maybe something you’re not aware of.” So you see.

Visitors is made up of only 74 shots, each lasting a little over a minute. Reggio has said he expected this to cause anxiety in viewers. I found the pace rather soothing. Shots held so long allow you to fall inside of them. Assuming you don’t become anxious, the pace will lull you. You may drift off. I don’t know that this is a fault.

No one makes movies like Reggio. You would be wise to see this one on a big screen while you have the chance.

If in the San Francisco Bay Area, this may be achieved beginning March 7 at the Embarcadero in S.F., and at the Shattuck in Berkeley.

Saw it at The Loft here in Tucson, but it left before I could go back and see it a second time. I was alternately fascinated, frustrated, invigorated, inspired, and puzzled by it. Definitely worth a second viewing.