Busy as I often am in the theater watching such less than stellar films as Captain America 2, and at home making sure the double features I write up are as wonderful as I imagined (Crimes and Misdemeanors plus The Player is even more perfect than I thought), I don’t always make proper time for the Most Important Classics Of Cinema. I’ve seen many, but there are gaping holes, such as the oeuvre of Robert Bresson, whose A Man Escaped, which I watched not long ago, was the first film of his I’d seen.

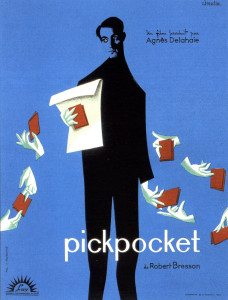

Second up: Pickpocket (1959), Bresson’s follow-up to A Man Escaped, which, minimalist and to the point as it is, has nothing on the minimalism of Pickpocket. Pickpocket clocks in at a concise 75 minutes. It tells the story of that very worst sort of leech on society’s soft underbelly, the pickpocket, here played by Uruguayan non-actor Martin LaSalle, who’s got intense eyes and wears jackets slightly too large. His character is, as I’ve already come to expect from Bresson, understated in the extreme. He says little, aside from his occasional narration, needed to let us know about any emotions he might be experiencing. His face and body language suggest little.

The movie begins with the pickpocket, Michel, at a horse race, where he slyly lifts a wad of cash from a woman’s purse. He’s nabbed by the cops, but they’ve got no evidence save the cash, so they let him go. Michel visits his mom, but won’t even see her, instead giving a neighbor, Jeanne (Marika Green, achingly beautiful), money to pass along.

Michel hooks up with another pickpocket, an expert, and learns more tricks. With a third man, they spend a day robbing people at a train station. This is the one exiciting sequence in the film, edited with loving care, all close-ups of faces and hands and wallets being slipped from coats, purses from under arms, watches from off of wrists. It’s played with quiet elegance.

I didn’t find much of anything else interesting in Pickpocket. I know I’m supposed to. Reading up on it, one would think Bresson is to movies what Dostoevsky is to novels, with Crime And Punishment often mentioned as its inspiration, or at any rate its spiritual cousin. Which in a very basic way one can see. Michel is indeed hateful of society and its rules and expectations, and he does see himself as a kind of superman, one whom society should allow to break rules as he alone sees fit. He tells the police chief this theory at one point. And at the end, Michel’s own overconfidence lands him in prison, where he is nevertheless loved by Jeanne.

Beyond those surface details, I’m not seeing the similarity to Crime And Punishment. Unrepentent petty thievery so one can eat is a far cry from a double axe-murder, the psychological and spiritual guilt of which drives one mad. And as accomplished a filmmaker as Bresson is, is his artistry in the brief sketch that is Pickpocket really on the same level as one of the great works by the greatest novelist in history? I’m going with no. But then I like to read.

So far, I appreciate the meticulous skill with which Bresson crafts his movies, enough that I’m going to keep watching them. I only wish I connected with them more. I understand he’s got one about a donkey sure to make me weep. Think I’ll go with that one next, barring any superheroes or giant lizards that get in my way.