We’ve all been there. In an alley. With a gun. A knife. A fist. Or with money, paying off a hit-man, not worrying about the grisly details. Sometimes people are inconvenient, is the thing, and what more convenient way to remove their inconvenience than by murdering them? It’s the best way. The simplest. What could go wrong?

A tell-tale heart? Is that what’s got you worried? You get away clean with the crime, but your guilty conscience yaps incessantly at your heels? Driven mad with remorse, you confess, and spend your remaining days in a five-by-five cell with a mute child molester named Leonard? Granted, it’s a distinct possibility.

You’ve got to maintain composure in the face of the cops. You’ve got to be strong. Admit nothing. Deny everything. Act innocent, but not too innocent. Only the guilty appear wholly without guile. The genuinely innocent seem suspicious, and are therefore not suspected. It’s a balancing act. Above all, you must do one thing, the one thing upon which your future hangs: you must forgive yourself.

In this week’s Mind Control Double Feature we peer deeply into the art of self-absolution.

Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

Woody Allen has directed over 900 movies, you may be surprised to learn. Among his very best is Crimes and Misdemeanors. It wasn’t a big hit at the time, but those in the know know that it’s a slow creeper of a movie, the kind that gets under your skin, that you find yourself thinking over long after it’s done. Also, there are jokes.

Woody Allen has directed over 900 movies, you may be surprised to learn. Among his very best is Crimes and Misdemeanors. It wasn’t a big hit at the time, but those in the know know that it’s a slow creeper of a movie, the kind that gets under your skin, that you find yourself thinking over long after it’s done. Also, there are jokes.

There are two stories entwined in the movie, thematically linked by the characters’ blindnesses and moral shortcomings. As Allen puts it:

Crimes and Misdemeanors is about people who don’t see. They don’t see themselves as others see them. They don’t see the right and wrong of situations. And that was a strong metaphor in the movie.

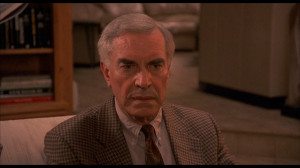

Martin Landau plays Judah, a wealthy, highly respected opthamologist. His life seems charmed, but for one nagging problem. He’s having an affair with Dolores (Anjelica Huston), and she’s reached the point of demanding he leave his wife. She threatens to reveal their affair otherwise. Judah is beside himself. What to do? He talks to his tough guy brother, Jack (Jerry Orbach), who suggests having her killed. Judah is outraged. He just wanted to maybe put a scare into her. Or so he says. But by the end of the conversation, he seems to be seriously considering the idea.

Meanwhile, Allen plays Cliff, a documentary filmmaker going nowhere fast, who despises all things popular and likely to make money. He’s currently making a film about an old philosopher, who opines throughout Crimes and Misdemeanors on matters of love and life. Cliff is hired by his hugely successful television producer brother-in-law, Lester (Alan Alda, in the best role of his life), to make a documentary about him. Lester is a pompous ass. But a smart one. Cliff falls for Lester’s assistant, Halley (Mia Farrow), who seems to be on his side in the culture wars. This half of the movie is the funny half. Until it isn’t.

Considering the theme of this double feature, I think it gives nothing away to reveal that Judah has Dolores killed. He is then faced with a problem: how to deal with what he has done?

He talks to his rabbi, Ben (Sam Waterson), who has some nice things to say, given the generality of the “problem” Judah brings to him, but who is blind to the ways of the world. Indeed, he is actually going blind. In their scenes, Judah seems to be talking to himself more than Ben, rationalizing what he’s done as best he can.

I probably shouldn’t say any more. In short, Allen weaves these strands together, these people who are blind to each other, to morality, to the world, eventually bringing everyone together in a final scene. Which scene includes a sort of recap of events of the film to the voice-over of the philosopher. Which sounds absurd, right? Nothing in how this movie is made makes sense. It simply shouldn’t work as well as it does. But damn does it ever.

This is pretty much Allen doing Dostoevsky. He’s not quite up to that heavyweight, but he’s dealing with similar themes, and coming to rather different conclusions.

At the end, Judah says that his life is like a movie, because how could his story be real? In our second feature, we dive deeper into the notion of reality as cinema (or vice versa?).

The Player (1992)

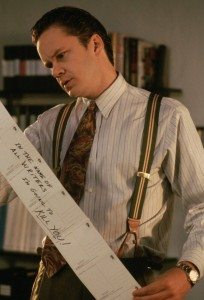

In which director Robert Altman skewers all things Hollywood. Who ever heard of a movie where the producer is the hero? It’s an outrage! Of course in the case of The Player, the producer, Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins), is as much the villian as the hero. He’s the subject, let’s say, the window through which we see the inner workings of Hollywood. It ain’t pretty. Everyone in the Hollywood of The Player is morally compromised.

In which director Robert Altman skewers all things Hollywood. Who ever heard of a movie where the producer is the hero? It’s an outrage! Of course in the case of The Player, the producer, Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins), is as much the villian as the hero. He’s the subject, let’s say, the window through which we see the inner workings of Hollywood. It ain’t pretty. Everyone in the Hollywood of The Player is morally compromised.

It begins with an uninterrupted seven and a half minute shot, moving through a movie studio, focusing on Griffin and his staff and various writers pitching stories, some of whom talk about famous long tracking shots, such as the opening of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. Yes, this is a movie as much about itself as about the business in general. Altman also loves to linger on old movie posters, slowly pushing in on their ominous titles, all portending doom for our hero.

Griffin, like all people employed anywhere in Hollywood, is panicked that he’s about to be canned and replaced by someone younger and meaner. Worse still, someone’s sending him vaguely threatening postcards. He thinks he knows who—a writer, naturally, upset at having had his pitch shot down.

Griffin tracks down the writer, David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio), attending a screening of The Bicycle Thief (a writer going to old movies alone? That doesn’t sound familiar at all), and asks him to cut it out with the postcards. Kahane isn’t especially friendly, they get into a fight, and there in the parking lot, well, Griffin fulfills the secret dream of every movie producer in Hollywood: he kills the writer.

Like Judah in Crimes and Misdemeanors, Griffin has to figure out how to cope with being a murderer. Will he learn to live with it? Will the cops nab him? Will he confess? For the time being, he doesn’t know. He’s too busy getting it on with Kehane’s girlfriend.

Altman, after making all kinds of weird and/or great movies in the ‘70s (e.g. M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Brewster McCloud, Nashville, 3 Women), had a rough time in the ‘80s, beginning with the reviled Robin Williams vehicle, Popeye. He came back big with The Player. It features a style perfected in Nashville where his actors are given radio mics and then set loose at party scenes and restaurants and so forth, chattering and talking over one another as in real life. Giving the movie a still greater fly-on-the-wall feeling are the vast number of cameos (over 60) by movie stars more or less playing themselves.

Throughout, Griffin slowly shepards a movie, Habeas Corpus, through the pre-production process, a movie with a grim ending. By the time we see the movie-within-a-movie (starring Bruce Willis and Julia Roberts, no less), do you think the ending has been changed?

The quote another great movie, The Player is “a cookie filled with arsenic.” It’s a delicious tale of Hollywood cynicism and depravity. I’m sure you’ll love it.

I was just thinking about The Player. I love Lyle Lovett and Whoopi Goldberg as the cops.