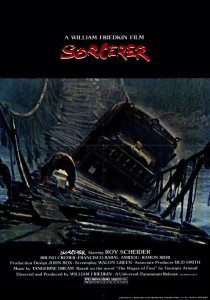

Sorcerer, William Friedkin’s gritty, arty, ’77 remake of the classic ’53 French action movie, The Wages of Fear, had the misfortune to open one month after Star Wars, replacing it at the Chinese Theater on Hollywood Blvd. It didn’t last two weeks before they brought Star Wars back. Sorcerer was a flop. Critics didn’t like it and audiences didn’t either. Friedkin’s career, previously red hot after making The French Connection and The Exorcist, tanked.

Since then, the movie has grown in stature, at least among those who like to champion underdogs. And finally, with Friedkin’s approval, it’s been digitally restored for blu-ray release, along with some theatrical presentations, like the one I saw in San Francisco at the Castro Theatre.

If you’ve seen any of the recent spate of highly touted 4K digital presentations of such classics as Lawrence of Arabia and 2001, you know that digital still has a long way to go before it looks as good as 35mm film (let’s not even bring up 70mm). On your big-ass plasma screen at home? They look fantastic, without a doubt. But blown up to big-screen size, even the best digital presentations look flat. Close-ups of faces are crawling with what I’ll incorrectly call ‘digital noise,’ and might better be described as millions of tiny worms wriggling furiously. Everything I read about these restorations praises their beauty, but I’m pretty sure every one of those reviewers watched the blu-ray on their TV. In movie theaters they continue to disappoint.

Sorcerer is no exception. It was nice to see in a theater, but a film print would have brought the experience alive. A shame, since the best that can be said of this ill-conceived remake is that it’s full of lovely cinematography. In everything else it’s lacking. Not everything. The music, by Tangerine Dream, is strangely atmospheric. That is, the atmosphere it creates is strange, and unexpected in a movie like this from this era. It’s the band’s first movie soundtrack. They’d go on to make many more.

Why is the movie called Sorcerer? There are no sorcerers in the movie. One of the two trucks our anti-heroes drive has the word painted on its side. It’s seen once. Presumably it had a certain artistic ring to Friedkin, something about unpredictable gods of weather screwing with our lives like an evil wizard, which is odd, seeing how he’d spent most of the ‘70s slamming people like Bogdanovich and Coppola and Scorsese for their arty European pretensions. Yet here he came, making his own bizarre hybrid, half art film, half gritty ‘70s action flick.

If you’ve seen The Wages of Fear, you know the basic story. If you haven’t seen The Wages of Fear, why are you sitting in front of your computer? Rent a blu-ray of The Wages of Fear immediately (or ‘borrow’ it from the interwebs, you tech savvy kids, you). I’ll wait.

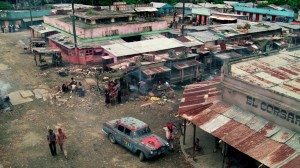

What a movie, right? Dated in appearance, but as for the action? The tension? The excitement? It remains as gripping as when it first came out, telling the simple story of desperate men in a dying South American town driving trucks loaded with nitroglycerin to a burning oil well, hoping against hope they don’t blow up on the way.

Friedkin’s version, scripted by The Wild Bunch scribe, Walon Green, is intentionally peopled by louses and lacking in anything approaching sentimentality. Friedkin’s attitude was that heroes don’t exist, only people trying to survive. Everyone is in part a bad guy as far as he’s concerned. We’re all stuck teaming up with people we don’t like in order to survive, which we won’t anyway. We’re all dead in the end. The movie is a metaphor for life on earth.

So, cheerful stuff. And not necessarily death to a movie. The ‘70s were a time of anti-heroes, and it sure worked in The French Connection. The problem with the characters in Sorcerer is not that they’re all introduced as thieves and murderers, it’s that we learn nothing about them as the film proceeds. Literally nothing. For Friedkin the point was to show character through actions, to pare away all dialogue and simply watch what these desperate men do, to connect with them in purely cinematic terms. Again, this is great when it works, but when your characters don’t actually do anything, how are we supposed to learn about them? Trying not to blow yourself up is a character trait shared by all humans. That these specific characters would also prefer not to be blown up tells us nothing.

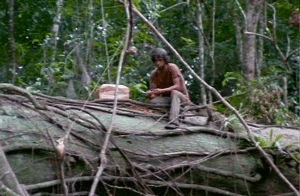

It’s easy to praise some of the truck-driving action sequences, particularly the bridge sequence, in which the two trucks, one after the other, are forced to cross a fragile wood and rope suspension bridge over a raging river in a jungle downpour. It took months to film, cost millions, looks great, and I didn’t a care a whit who lived or died. Friedkin works so hard to eliminate anything resembling sentiment he eliminates anything related to character in the process. It’s baffling.

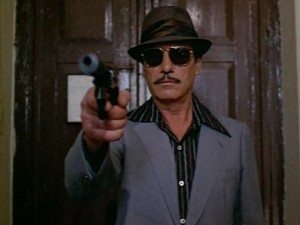

Unlike Clouzot’s version of the story, which begins in the South American town, Friedkin opens with four vignettes from around the world, in which the four main characters are introduced. One is a hit-man. Without a line spoken, he shoots a guy dead. Another is a Palestinian terrorist who blows up a building in Jerusalem. Another is a French businessman who defrauds the Paris stock exchange. After his partner commits suicide, he abandons the country and his wife. The last is a New Jersy crook, played by Roy Scheider, who inadvertantly robs a mafia leader, then crashes the getaway car. Hunted by the mob, he flees the country.

These stories take a long time to tell. What do they give us? Nothing. It’s all backstory. Why do we need to know what drove these men to South America? Isn’t their haunted desperation enough? If what they did in their intros had some bearing on their later actions, or on their characters, or on anything, the scenes might have value. As it is I sat in the theater for a half hour wondering when the movie was going to start.

The South America of Sorcerer is steeped in the real. It’s not a “movie town” like Clouzot’s was. It’s wet and dirty and spread out in the jungle and in the bar Scheider frequents the woman washing the floors is far from “movie attractive.”

One might think this would be the time to get to know the characters, to sit with them, to see how they behave in general and toward one another, to learn something, anything, about them aside from the criminal nature of their backgrounds. But it is not to be. The characters remain ciphers.

Eventually we get to the well blowing up, the fire, the discovery of leaky old nitroglycerin, highly unstable, and the need for drivers to make a suicidal mission.

Our four not-heroes show up. Scheider gets in a truck with the hit-man, who we pretty much haven’t seen at all save his intro. He’s not spoken a word. What he has done is kill the old German who was supposed to be the driver. Scheider doesn’t care. They take off together.

Maybe it’s not fair to compare Sorcerer to its predecessor, but who said life is fair? In the original movie, these two characters are well known to us and have a clear relationship, the status of which is reversed over the course of their perilious journey. You like them, despite their faults, or even because of them. They’re real people. You want to see them survive. You’re with them in the struggle.

In Sorcerer we don’t know anything about the hit-man, and he and Scheider have no relationship, having never met as far as we’ve seen. In the other truck is the financial crook and the terrorist, neither of whom we’ve seen do anything. That’s not true. The financial crook chats briefly with Scheider, who buys him a drink. And the terrorist runs at the hit-man with a knife when he finds the dead German. Fascinating stuff.

It feels like Sorcerer wants to be The Treasure of The Sierra Madre or Aguirre, The Wrath of God, but how can it make such a claim when those movies succeed almost purely on the strength of their characters?

The end of The Wages of Fear is not a happy one, but it’s thematically resonant. The men are doomed from the start. The only question is how they’ll meet their maker. Friedkin wants to tap into the same power of fate for his version. He comes up with a different demise for Scheider, one that couldn’t feel more forced. And besides, who cares what happens to Scheider?

Sorcerer had far too much going against it to succeed in ’77. A title nobody knew the meaning of, especially deceptive coming from the famous director of The Exorcist. Would magic or demons play a part? No name actors aside from Scheider, who does a fine job as always, but even after Jaws he didn’t have the name value of Friedkin’s first choice for the role, Steve McQueen. And a first quarter—the first three intros—all in a foreign language. The studio actually put up notices on posters at theaters assuring patrons that the movie was primarily in English.

That the movie is wilfully empty of character and emotion can’t have helped either. Sorcerer went far over budget and didn’t make back even half of what was spent. It signalled the beginning of the end for the style of dark movies briefly popular in the ‘70s, a style in part pioneered by Friedkin. Sorcerer is looked on far more favorably today, with some (Friedkin himself, for one) calling it his masterpiece. Strange, that. Maybe they haven’t seen The French Connection lately.

Agreed. Watching Sorcerer, what I missed most was the relationships. Mario, Luigi, Jo, Bimba, Princess, Koopa, and Donkey Kong — these were all people whom I understood and cared about. The effects of the tension on their relationships, that’s what made the tension unbearable.

When Scheider drove over the hit man on the bridge, not only did I not care if he was hurt or not: I couldn’t tell. In Wages of Fear, Jo being dragged under the truck in the lake of oil… MIND EXPLODE. Would you be able to do that to Jo if you were Mario? What has this situation done to you?

There was zero of that in Sorcerer — except at the end, when there is a nice bit with Scheider walking the final kilometer or whatever carrying the nitro. And the ending; bah.

The French Connection is 1000x better. I think I even liked Bug better.

Will definitely watch this. I really like Friedkin’s films.