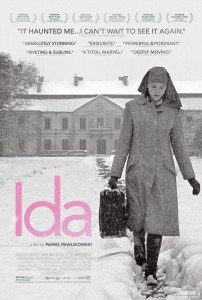

Pawel Pawlikowski’s new feature, Ida, reminds me of Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and I don’t think that’s a coincidence. Like that early masterpiece, this film investigates, in black & white, what we do out of religious conviction. It is also hypnotically beautiful and raw.

Ida tells the story of Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), an orphan of age who is preparing to become a nun in Poland. Before she takes her vows, her mother superior insists she meet her only living relative, an aunt named Wanda (Agata Kulesza), of whom Anna has had no knowledge. Anna leaves her convent as innocent as a fawn. Her face, lovely beneath its wimple, shies away more often than not in the bottom right of the frame.

Ida tells the story of Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), an orphan of age who is preparing to become a nun in Poland. Before she takes her vows, her mother superior insists she meet her only living relative, an aunt named Wanda (Agata Kulesza), of whom Anna has had no knowledge. Anna leaves her convent as innocent as a fawn. Her face, lovely beneath its wimple, shies away more often than not in the bottom right of the frame.

In the concrete city Wanda tells Anna that she is Ida; that her parents were Jews, murdered during the war. So it becomes clear that Ida takes place in the early 1960s and not in some timeless void of convent existence. Anna lives without history, but Ida occupies a spot in time, and a difficult one.

Of these difficulties, Wanda is aware. She works as a legal official of some sort, highly placed in the Communist Party. Her arteries are clogged with suppressed anger. She is a Jew. Her family was killed. Now she stands judge over men who vandalize flowerbeds.

Together, Ida and Wanda go in search of their family’s bones. To know.

Together, Ida and Wanda go in search of their family’s bones. To know.

Shot in the near-square 1.37:1 aspect ratio, cinematographers Lukasz Zal and Ryszard Lenczewski do much with only light and line. Where most films depend on what fills the frame to convey meaning, Ida uses the frame to give meaning to what’s contained. Ida’s face, for example, hiding in a corner. Shadows spilling down spiral stairs. The light ahead, pouring down the tunnel of trees, lighting Wanda’s eyes as reflected in the rearview mirror.

Zal, Lenczewski, and Pawlikowski milk the convent and its inhabitants for each dart of light. They make these early scenes — and the ones that follow — beautiful in their ordinariness. Their compositions are elegant and calming. It makes the film seem like looking through a stained-glass window into a barn. As in Dreyer’s much earlier picture, Ida is a film of faces. Unlike with Dreyer, these faces shy from attention. We see the world the faces inhabit.

Zal, Lenczewski, and Pawlikowski milk the convent and its inhabitants for each dart of light. They make these early scenes — and the ones that follow — beautiful in their ordinariness. Their compositions are elegant and calming. It makes the film seem like looking through a stained-glass window into a barn. As in Dreyer’s much earlier picture, Ida is a film of faces. Unlike with Dreyer, these faces shy from attention. We see the world the faces inhabit.

It is that world that is subject, more so than even Ida.

The film resists telling you what you know. If there is a scene in which what will happen can be guessed, the scene is skipped. This covers a lot of what fills most modern films: the end and the beginning. Instead we see a man crying in a grave and there is beauty there. We see the wrath of the despondent and there is beauty there. We see the tended garden of Christ, walled in circular stone, and there is beauty there.

The film resists telling you what you know. If there is a scene in which what will happen can be guessed, the scene is skipped. This covers a lot of what fills most modern films: the end and the beginning. Instead we see a man crying in a grave and there is beauty there. We see the wrath of the despondent and there is beauty there. We see the tended garden of Christ, walled in circular stone, and there is beauty there.

Ida runs short at 80 minutes but it feels complete. Ida learns what she needs to know about the world, about skulls, about Coltrane, about humankind. When she returns to the convent, she is not so innocent, but she’s still a fawn. As she wills. As she wants.

Ida opens May 23rd at San Francisco’s Clay Theater, at the Camera 3 in San Jose, and at the Christopher B. Smith Rafael Film Center in San Rafael.