When I saw Children of Men for the first time, it grabbed me instantly. I mean the first shot came on screen, nothing notably special about it, and the movie had me in its grip. The first shot continued, followed a man outside a coffee shop into a dirty future street, and the shop exploded. The title filled the screen. I was hooked.

It’s hard to say what about the initial image grabbed me when I’d yet to see anything that followed. How does a filmmaker suck me in like that? Surely it has everything to do with the filmmaker’s skill at imparting their vision. Every frame of the movie is imbued with it. It ripples from the screen. One can take it apart technically—the lighting, the framing, the production design, the commitment of the actors, the dialogue—but in the end it’s the whole manifested by those elements that one responds to, and the whole can’t be defined by its parts. The whole is something beyond. It’s art.

I used to read scripts for a studio. Most were bad. Almost all of them, good or bad, revealed themselves on the first page. The good ones grabbed me, the awful ones I knew were awful within a page. Didn’t mean they were illiterate (though some were). Didn’t have to do with something “exciting” happening or not. It was something else. A writer not in command of what they’re doing reveals themselves instantly. The opposite of art, then.

Which brings me to The Double (not to be confused with The Double or The Double), a new movie by writer/director Richard Ayoade based on the novella by Dostoevsky, starring Jesse Eisenberg as Simon James, a meek office clerk in an oppressive, eastern Europeanish, ‘80s-ish world.

It begins with a close-up of Simon riding a subway. An unseen man stands before him, says, “You’re in my place.” Cut to Simon’s POV of the empty subway car. Simon stands, the man sits in his spot, his face obscured by a newspaper.

Perfectly reasonable beginning. Maybe a little on-the-nose with the dialogue. Shot with evident style, a bleak, dark subway car, old and awful. Simon wearing a suit slightly too large for him.

And the movie had already lost me. From the first close-up something was wrong. How could it have struck me that way from the outset? I don’t know. But there it was. It never improved. I disliked the whole movie. Nothing ever clicked into place. Which considering the obvious effort that went into its making, I find a bit strange. Maybe I shouldn’t. Art is mysterious that way. Sometimes everything falls into place. Other times nothing fits.

And of course, as the internet often tells me, your mileage may vary. Maybe this is art of the highest order for some people. And then again, maybe those people are crazy and should be tied to the underside of wild moose and released into the snowy Canadian wilderness come new year’s. I don’t know. I don’t write Canadian law. (Yet.)

Simon works in a typically oppressive office for this type of story, this type of story being Brazil meets Kafka meets, well, Dostoevsky. It also reminded me of the opening office sequence to Joe Vs. The Volcano (a movie that is much better than you think it is). He is confronted by typical Kafkaesque issues like his ID card not scanning and having to fill in a form as a guest even though he’s been walking past the same security guard for three years. The madness of modern society, you see.

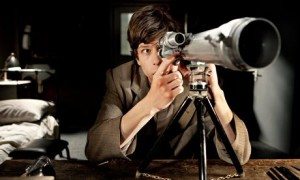

He’s got a thing for a girl in the copy-room, Hannah (Mia Wasikowska), who’s lovely and sweet. His boss is Mr. Papadopoulos (Wallace Shawn, always a pleasure to see). He lives in an oppressive apartment building we only ever see at night. He watches a man jump to his death across the way. The cops tell him suicides are rampant. I guess we know what’s coming for Simon by movie’s end.

What’s going to drive him to suicide? His double shows up. James Simon, identical, also played by Eisenberg. Only this version of himself is outgoing, daring, witty, and everyone loves him. Simon is aghast. He starts hanging out with James, who tries to coach him in picking up girls, Hannah in particular. But of course it’s James Hannah is attracted to and starts seeing. Things get darker as Simon tries to rid himself of his double. It ends violently. And with the implication—wait for it—that they’ve been the same person all along.

Which is fine. It’s been done many a time before, at least as far back as, well, as Dostoevsky writing a novella, but the split personality personified, it’s compelling stuff. Why it’s not compelling here is the mystery.

I think Ayoade becomes confused by his metaphor. He’s not sure whether to present events as though they were really taking place, thus making us infer the metaphor, or to present them overtly as metaphor. Or rather he takes different tacks at different times, turning the movie into a somewhat sticky morass of muddled emotions and movitivations.

The setting is another curious attempt at something unclear. It’s essentially a riff on Gilliam’s Brazil, which took place “Somewhere in the 20th century,” and featured imaginary computers and office equipment cobbled together from a century’s worth of technology. In The Double, we seem to be in an imaginary 1980s, with likewise imaginary office equipment operated by buttons and levers and whatnot. Furthering this vibe is a science fiction TV show Simon likes that looks a bit like if the 1980 Flash Gordon were a BBC program. It’s a fine idea, it looks weird and different, and I felt like it belonged in a movie other than the one I was watching, one where it might have been funny.

A key element missing from The Double is humor. Attempts are made, typical of the genre, the ludicrous nature of bureaucracy, the ineffectual man caught in its gears, but none of them are actually funny. It’s not light on its feet, this movie. It’s leaden. People too often think of the surreal when they think of Kafka (perhaps only having familiarity with The Metamorphosis), but one must remember that Kafka found his stories hilarious. The Trial to him was a laugh riot. And it is funny. Only you have to have an appreciation for the absurdity of the human condition to get the joke. Terry Gilliam got the joke in Brazil. Martin Scorsese got the joke in After Hours. In The Double, the jokes are as empty as the characters.

I imagine The Double will find an audience, albeit a very small one made up primarily of depressive Jesse Eisenberg aficionados. They will obsess over the movie. They will make their friends watch it. They will insist it’s an overlooked masterpiece. I, however, will be the one tying those people to wild moose.

Quote: “When I saw Children of Men for the first time, it grabbed me instantly. I mean the first shot came on screen, nothing notably special about it, and the movie had me in its grip. The first shot continued, followed a man outside a coffee shop into a dirty future street, and the shop exploded. The title filled the screen. I was hooked. …”

Ditto! I had precisely the same experience with Children of Men. And the film kept me on the edge of my seat and sometimes barely breathing from the first moment to the last! That uninterrupted camera with long pans and almost no cuts had such a strong lure, it felt like following a real time documentary in some way, it felt honest. And then it offered those textures in every frame that somehow did it for me visually as well. But it is the compelling story behind, translated into perfectly matching honest imagery, in my belief.

I know, I need to read your review now!