It is from the soil of sketchy histories that the most enduring myths grow. A thin outline of facts may be claimed to contain any number of stories. It’s up to the teller to decide what to include, what to leave out, what to emphasize, what to diminish. History isn’t what happened; it’s how it’s said to have happened. It doesn’t exist as a thing; it may not be re-lived. The past exists only as a story. How that story is told reveals as much if not more about the teller than the events recounted.

The myth of John Smith and Pocahontas (a nickname; her real name was Amonute) is hard to shake. A romance told against the backdrop of two worlds meeting, where one would destroy the other. What could be more romantic? More sad? More beautiful? More portentous? More of whatever whoever’s telling the story wants it to be? Is it any wonder it’s entirely made up?

There was no romance between John Smith and Pocahontas during his years in the Virginia colony (1607 to 1609). No romance was so much as intimated until two hundred years later at the start of the 19th century. With the recently created U.S. of A. expanding rapidly, turning the history of the Jamestown settlement into a romance must have felt dreamily nostalgic.

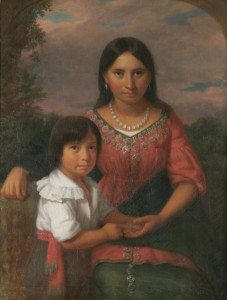

Pocahontas was between ten and twelve years old when she met John Smith. If there was indeed some sort of terribly inappropriate romance between Smith and this young girl—as any romance between the two would have been—no one described it at the time. Nevertheless, the myth shows no signs of fading. It’s too good to give up.

William Vollmann is a writer keen on destroying the myths told by victors in cultural clashes. In his book Argall, he digs deep into history and emerges with a 700 page, novelistic account of John Smith, Pocahontas, Samuel Argall, and many others, volume three in his Seven Dreams series, each written in his dense, hallucinogenic style, with Argall being stranger still, written in Vollmann’s own version of 17th century Elizabethan English, that brings to life the past so vividly it’s difficult not to believe this is how it must have happened.

The paperback, in a brilliant move, includes, on the opening page devoted to quoting critical raves of the novel, this snippet from the L.A. Times (to which review Vollmann himself wrote a hilarious response):

The book’s first sin consists in its so-called Elizabethan language, whose archaisms, variant spellings and preposterous figures of speech substantially impede the reader…second, and worse, Vollmann insists on retelling the revered legend of Pocahontas in the ignoblest possible terms. The majestic Indian princess gets reduced to childish victim, John Smith is a double-hearted, ultimately impotent adventurer and everybody else comes off much worse…In the end, we begin almost to feel that this author believes that this America of which we’re so proud was never even worth hacking out of the wilderness.

A beautiful summation of his work! Indeed, why would this Indian (an English term (what? this isn’t India?)) princess (also English, meaningless to the natives) be seen by Vollmann as a childish victim? Because she was a teenager when Argall kidnapped her and imprisoned her in Jamestown, where she was married to a white man, John Rolfe, who brought her to England where she died at age 20 or 22, never to see her home or family again? How could anyone think such doings ignoble?

Was this America of which we’re so proud worth hacking out of the wilderness? I have the sense that one population of people, the ones the English found happily living here, might think not. The “wilderness” was their home. It required no hacking.

As for John Smith, he was a man known for telling tall tales, for irritating—at best—everyone he met, for trying in desperate and annoying fashion to better his social position (he never did), for spending close to two years in the Virginia colony extorting food from the natives and using his friendship with Pocahontas to better the English position and weaken that of the natives, and for ultimately being shipped back to England due to a nasty gunpowder accident, an utter failure as a colonialist. He never returned.

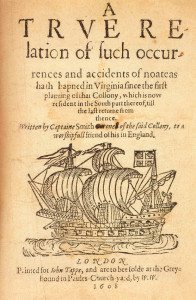

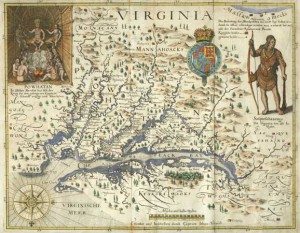

On the plus side, he mapped a great number of rivers and territories, his extortion and lies kept enough colonists alive to maintain the colony, and his accounts of the colony give us one of our few contemporaneous windows onto the period. Part of the difficulty in understanding what really happened to Smith in Virginia is that his two accounts, one written in 1608, while he was still there, and the other, a letter to Queen Anne eight years later, differ in their details.

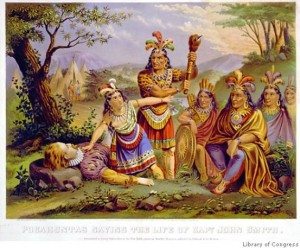

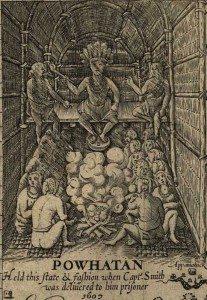

In his first account, he describes his meeting with Powhatan, so-called (by the English) king of the natives (he was a powerful leader of a number of united tribes), but doesn’t mention almost being killed and Pocahontas intervening to save him. He describes initially meeting her some months after a non-lethal encounter with Powhatan. In his letter to the Queen, written on the occassion of Pocahontas arriving in England and wishing to meet the Royals, the story changed. Here he writes of being captured, of savages about to kill him, and of Pocahontas saving him from death, almost as though, one might imagine, he wanted to impress the Queen and further embellish the notion that Pocahontas loved the English.

More curious still, years later, in writing about his youthful adventures in Turkey (which went down some years before he sailed to America), he relates an identical escape from death: captured, about to be killed, saved by a young woman enamored of him. Seems as though young princesses couldn’t resist him. John Smith was renowned for his tall tales. Few sound taller than this one.

Argall is the story of two colliding points of view, and Vollmann’s goal is to fully embody them both. He doesn’t sentimentalize the native Americans. Instead he brings them to life as people, same as the English, whom he doesn’t demonize, despite their most insidious atrocities. He takes the facts as we know them, and from them spins his tale inward.

He includes the famous scene of Pocahontas saving Smith from death at the hands of her father, thus beginning their friendship. He includes Pocahontas marrying Kocoum, a Patawomeck, a much debated part of her history. He includes the politics of the colony. He includes the intertribal wars of the natives. He includes every known murder and massacre by both sides. And he leaves out any romance between Smith and Pocahontas. Vollmann’s method is to strive for the poetic truth of this history. His Seven Dreams are “symbolic histories.” To each side of these culture clashes, the other is an unknowable phantasm, as mysterious as a dream. Vollmann works his way inside the heads of the protagonists, imagining their thoughts, showing us the logic of their actions as they see it.

Ultimately, Vollmann’s account is almost unbearably sad. How could it be otherwise? Pocahontas, a young girl, befriends the English her father is rightly suspicious of, and weekly brings them food, assuring their survival. As the English woes increase, Smith sees her less and less, meanwhile stealing corn from other tribes, before returning to England. Pocahontas is told he’s dead.

Beginning in late 1609, the English murder numerous natives, and the natives retaliate by massacring a group of English led by one-time colony president Ratcliffe. And so it goes, back and forth. Argall and others burn native towns and massacre their populations. Women in Queen Opposunoquononuske’s town of Appatamuck lure twenty English soldiers into their beds, then kill them. Finally Argall hatches a plan to kidnap Pocahontas with the aid of natives desirous of currying favor.

She’s held hostage in Jamestown, bringing a brief peace, and, after converting to Christianity and changing her name to Rebecca, is married to English widower John Rolfe. They have a son, Thomas. They travel to England. She dies. Rolfe returns to Virginia without his son, remarries, and never sees Thomas again. He becomes rich growing tobacco.

Sad, indeed.

In his film The New World, writer/director Terrence Malick approaches the story purely from the angle of mythic romance. I watched The New World recently, the long version, and found it hard to take. As directed by Malick, it is astounding in its beauty. I love the way Malick moves the camera, the way he edits, the lack of dialogue, the music. All of these elements impress. What’s hard to get around is the way he chooses to tell this story.

In his film The New World, writer/director Terrence Malick approaches the story purely from the angle of mythic romance. I watched The New World recently, the long version, and found it hard to take. As directed by Malick, it is astounding in its beauty. I love the way Malick moves the camera, the way he edits, the lack of dialogue, the music. All of these elements impress. What’s hard to get around is the way he chooses to tell this story.

In Malick’s version, Pocahontas (Q’orianka Kilcher) is a ravishing beauty in her early twenties. She wears stylish deerskin leggings and twirls in the grass. John Smith (Colin Farrell) is a dashing, moody nature-lover, who secretly wishes to be one with the “naturals.” In short, he’s every white character in every movie ever made about culture clashes. He’s the one we, today’s audiences, relate to. Why? Because we believe, deep in our hearts, that if we were in Jamestown in 1607, we’d befriend the natives. We’d stand in awe of their simple spirituality. We’d treat them with the dignity our present-day morality demands. Smith in The New World is indistinguishable from Kevin Costner’s character in Dances With Wolves, or Tom Cruise’s in The Last Samurai. He’s our image of ourselves cast back in time to right the moral wrongs of our ancestors.

That Malick treads this familiar path is depressing, more so in that he grossly alters real people and events in order to do it. Everything in his telling is distorted, all to the end of rendering the clash of cultures as a beautiful doomed romance. In his own time, Smith burnished his own image in the stories of his exploits, but he wouldn’t recognize the man Malick turned him into. Smith wasn’t shy about how he exploited the natives, how he extorted corn from them, how he gave them worthless beads, how he lied to them about essentially everything. Malick eliminates all of this, instead having Smith, in the kind of dreamy voice-over Malick always uses, yearning to become one with the natives and with his true love, Pocahontas, who’s presented as a clichéd white man’s fantasy of nature-girl femininity.

Is that Malick’s point? That Pocahontas is an unreal fantasy dreamed up by the English? It’d be interesting if it was, but Smith is equally fantastic. They’re the leads in this romance, and we’re supposed to feel that each is presented with emotional depth. Stepping back to look at the larger picture, what point is Malick trying to make here? Is he telling us that this meeting of worlds is a poem of doomed love? Two cultures unable to find a common ground, destined to forever be apart?

If so, it’s no different than every romantic retelling of the story from a British or, later, American point of view. It turns a terrible history of conquest into something nostalgic and romantic. Even though Malick goes to enormous pains to render the natives as “realistically” as possible—great historical reverence is given their spoken language, their attire, their weapons—he presents them as the standard white cliché of perfect spiritual innocents. All is peaceful nature until the English show up.

Another telling choice: as if Smith wasn’t enough of a moody romantic, Christian Bale plays John Rolfe as a sad man with a big heart, who falls for the beauty Pocahontas the moment he sees her. As the movie ends, and Pocahontas dies, Rolfe takes their son, Thomas, on the ship back to Virginia. If we don’t see our modern selves, and our modern values, in Smith, surely we may find them in Rolfe. He loses Pocahontas, but their son forever binds them. Only recall that in fact Rolfe left Thomas in England, married an English woman in Virginia, had children with her, and never saw Thomas again.

Malick appears to have no interest in shining a light on the history of the times. His alterations, simplifications, and elimination of that history don’t lead to a deeper understanding of what happened, poetic or otherwise; they conspire to romanticize a notoriously dark history, changing it into the story of a pure-hearted Englishman unable to overcome the baser instincts of his brothers, leading not quite to tragedy, but to a certain amount of wistful sadness.

Is it any surprise that Disney’s ’95 animated musical, Pocahontas, is even worse? I watched it after The New World, curious to see if they’d gloss over history as blatantly as Malick. They do. At least Malick has beautiful, unique filmmaking going for him. Pocahontas has nothing going for it. The songs are awful, the animation is half-hearted, the story is wafer thin, and history is turned on its head. It’s a far, far cry from Disney’s modern heyday of The Little Mermaid and Beauty And The Beast.

Pocahontas (voiced by Irene Bedard) is, as I expected, animated to look like a twenty-something European supermodel, with skin tinged faintly brown and a slight Asian cast to her features. John Smith (voiced by Mel Gibson) couldn’t be funnier. He looks exactly like He-Man, a muscled giant with flowing blond hair. On the journey across the Atlantic, he dives into the ocean mid-storm to save a dying man, so heroic is he. In truth, Smith was accused of mutinous speech during the trip, locked up belowdecks for the rest of the journey, and only grudgingly pardoned on arrival owing to papers appointing him to the counsel (which politics are never mentioned anywhere in The New World or Pocahontas, though Malick has Smith arrive in chains).

In the Disney version, the scene where Pocahontas saves Smith from death isn’t when they meet, it’s the climax of the movie, following a lengthy romance. The movie doubles down on the disputed notion of Pocahontas’s marriage to Kocoum, with her father, Powhatan, insisting she marry him, thus driving the plot. She’d much rather marry John Smith. Smith and Pocahontas want peace between the English and the natives, but after Kocoum is shot by a dopey English lad (voiced by Christian Bale, no less), the two sides declare war. Ratcliffe is the bad-guy (I assume because of all the historical leaders of the colony, he’s got the most Disney-fied evil name).

Smith is to be executed (wrongly, for the murder of Kocoum). Pocahontas throws herself on him. War is averted! But wait, Ratcliffe refuses peace. He shoots at Powhatan—and John Smith throws himself in harm’s way. He takes the bullet, and must return to England to be healed.

So in the end, the white man wins the heart of the native girl, kills her would-be husband, saves her father, and brings peace to the new world. Powhatan and Pocahontas look forward to his speedy recovery and return. It’s hard not to find this telling problematic from, say, a moral point of view.

Malick turns John Smith into a surrogate for modern audiences—modern British and American ones—to experience the beginning of a centuries-long genocide as a romantic interlude, a tone-poem sad and beautiful, while Disney goes for something even simpler: a feel-good love story, two cultures working together for mutual peace, and a happy ending where the white man saves the day. I can’t imagine either one set out to perpetuate racial stereotypes. In fact both go to evident lengths to create stong native characters and nefarious English ones. But by telling the story of John Smith and Pocahontas as a romance between adults, they shoot themselves in the foot. That foundational decision alone dooms them. Every historical alteration is colored by it.

All three of these tellings offer different perspectives on the truth. Because there is no “truth.” There are only versions of it (see: Rashomon). What makes them different is their intent. Vollmann’s is to create history through the embodiment of its players, and he does it brilliantly. Helps that he has the form of a novel to work with. No movie about Smith and Pocahontas is going to go as deep as Vollmann does in Argall. Simplifications must be made. The question is, what ends are being served by those simplifications? What story is being told, and why? It’s hard to care about a clunky Disney musical (then again, its audience is kids–we should care even more), but The New World left me baffled. Why tell this lie? Why perpetuate this myth? Malick, interested in the poetry of a star-crossed romance, loses the forest for the trees.

Just watched the Terrence Malick. Good critical review of it in terms of historical inaccuracy.