(In which series I intend to watch every Planet of The Apes movie ever made, beginning with the original classic, Planet of The Apes, and continuing through summer 2014′s newest entry in ape-lore, Dawn of The Planet of The Apes. Join me, and we will lose our pitiful human minds together.)

If there’s one good thing to be said about Battle For The Planet of The Apes (1973)—and there is indeed only one—it’s that the previous three movies in the series are retrospectively brilliant in comparison. Suddenly those hours spent gaping in disbelief at Beneath, Escape, and Conquest no longer feel wasted. They feel like a master class in the subtle art of cinema.

Battle isn’t so much made up of scenes as it is of gestures. You know what’s going on, but it’s as though, lacking an actual script, the actors were told to make up random words to be overdubbed later with proper dialogue, which overdubbing never came to pass. Paul Dehn, writer of the previous three sequels, wrote a treatment, then handed off scripting duties to John and Joyce Corrington, who had never seen the previous movies. Dehn came back to fix up their finished script. He changed the Corrington’s final scene—of ape and human children fighting on a playground—to one where children are being taught by the Ape Lawgiver, with a final shot of a statue of Caesar, erected 600 years earlier, shedding a single tear. Joyce Carrington called Dehn’s ending stupid. “It turned our stomachs,” she said when she and John saw it, to the uproarious laughter of everyone who’s seen Battle.

The poor Corringtons. Their beautiful vision ruined by a different ending. A fate befalling even the worst writers, of whom they are two.

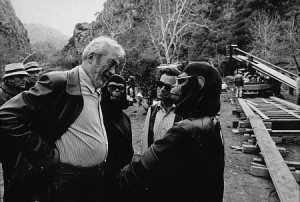

Speaking of the Ape Lawgiver, whose “600 years in the future” speechifying to the childrens bookends the movie, he’s played by John Huston, who, old and insane, thought he’d actually be flying a spaceship to a planet ruled by apes when he signed on to do this picture.

I’m kidding, of course. Surely it was the draw of wearing a cheap ape mask that lured in Huston. And cheap it was. The devolving ape masks are the clearest indicator of the smaller and smaller budgets each of the Apes movies had to work with. Battle is the cheapest, and looks every penny of it.

The story takes place after a nuclear war between apes and humans, but exactly when is unclear. The returning characters all look exactly the same age as when we last saw them in Conquest. One character says it’s been about ten years since the end of the last movie, another implies that it’s been closer to thirty. I think it’s safe to say that no one making the movie knew or cared about such fine points of logic and continuity.

The apes, ruled by Caeser (Roddy McDowell, back for more), live in a forested area in relative peace, with humans working for them as, more or less, slaves. Back in Conquest, all ape species, we were surprised to learn, had learned to walk upright, wear clothes, and perform simple tasks in a mere twenty years. None, however, could speak. As Battle begins, all apes can speak. They’re all as smart as Caesar. They are, in other words, identical to the apes we met in the first movie, 2,000 years in the future. Which makes sense because [Ed. note: sentence missing.]

Caesar’s human advisor, MacDonald (Austin Stoker), played by a different actor than the MacDonald of Conquest, but who is in fact, we are told twice, the brother of that previous character (because god forbid any element of continuity be unclear in this film), tells Caesar that back in the bombed-out, irradiated city are tapes of his parents, who died shortly after Caesar’s birth. He takes Mac and a scientific-minded orangutan, Virgil (Paul Williams, who, sadly, does not break into song), on a trip to this so-called Forbidden City, despite the risk of radiation.

There they find the tapes, but they’re seen by the surviving humas, who have gloop on their faces indicating radiation poisoning. They’re led by Governor Kolp (Severn Darden), whom you’ll recall as the evil inspector from Conquest. Seeing the apes, he decides it’s time to start up the war again, and sends spies to find out where the apes are living.

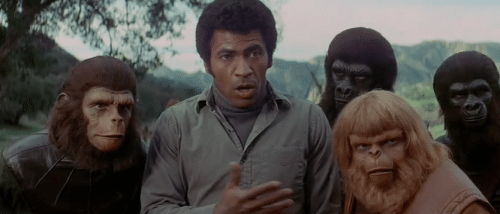

Our heroes, Caesar, Mac (brother of the other Mac, just to be clear), and Virgil, as they sing “Rainbow Connection”

Meanwhile, back in apetown the gorillas are all about waging war on the humans. Their general, Aldo (Claude Akins, famed actor in many a TV western), wants to kill their human slaves and, we learn in a secret meeting, he wants to kill Caesar too.

But lo! Who’s that in a tree? Why, it’s Cornelius, son of Caesar, chasing his pet squirrel! (I did not make that up). Aldo climbs up the tree after Cornelius and hacks away at a branch until Cornelius falls to his presumed death.

The gorillas declare marshall law and lock up their enslaved humans, while Caesar remains curiously oblivious, and tends to his unsconscious son. Mac is smart enough to examine the broken branch and notes the machete marks, but he only tells Virgil, who keeps the info secret until the plot requires him to reveal it.

First up: war! The radiation humans show up in their two jeeps and a schoolbus, and as you can imagine–as in fact you must imagine, because they barely had the money to film it–it’s a terrifying battle. Things blow up. Well, one thing, at least. Everyone shoots at everyone else. Finally the humans storm the defenses and find the apes lying around dead. Suspiciously “dead,” one might think. If I was Governor Kolp, I’d have instructed my men to go ahead and shoot the apes in the head, just to be sure. But Kolp, drunk on the wine of victory, fails to take this step. He corners Caesar, exchanges some nasty words, and is about to shoot him when the apes leap to their feet and rout the human intruders! Hooray!

Caesar allows the surviving attackers to run away, but Aldo intercepts their retreating schoolbus and massacres the lot of them, including Kolp.

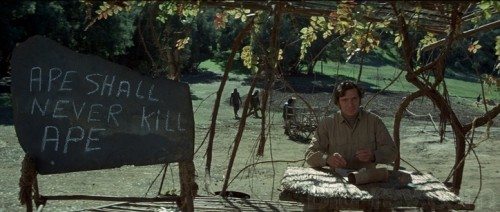

Caesar is about to release the human slaves from their cage when Aldo demands they all be shot. It is now that Virgil reveals who killed Cornelius (who, by the way, died a few scenes ago): Aldo! Aldo broke the prime ape law: ape shall never kill ape. Every ape in town is aghast, even the gorillas who watched Aldo kill Cornelius in the first place. More like weasels than gorillas, you ask me! Ha ha! Ha. Sorry.

Aldo does the only logical thing: he runs up a tree. Caesar follows. Yes, the climax of this movie is two guys in bad ape masks slowly climbing up an oak tree, ending when Aldo slips and falls.

MacDonald, freed from his cage, pleads with Caesar to release the humans from their apish servitude, so that apes and humans may live together in peace. Caesar thinks this is a totally groovy idea.

But we don’t cut to 600 years in the future and the Lawgiver and the kids and the crying statue, not yet. First there’s a last scene back in radiation-city. Before leaving for battle, Kolp told his assistant to launch their lone remaining nuke if they should lose the fight. They lost. His assistant readies to launch—but Lt. Mendez begs her not to do it. He says the bomb is the Alpha-Omega bomb, and will destroy all life on earth. He says they should venerate this bomb instead. She relents.

And so we see what will become the creepy mutant bomb religion in Beneath. It all ties together, people! There is no escaping fate! A grand circle of death! Ending with the final destruction of planet Earth!

Like a soothing children’s bedtime story, these Apes movies.

That’s it for the original series. What did I learn so far? I learned that if you make a movie as compelling as Planet of The Apes, you can milk it dry in four sequels.

Or can you? You may have to wait a few years for the memories to fade, for the psychic wounds to heal, but the apes will return. I know, let’s hire Tim Burton to direct a remake of the original for 20 times the budget. It’ll be a smash! Think of all the sequels we’ll get out of it! This can’t fail! (Stay tuned for failure in our next installment.)

The Going Ape series: