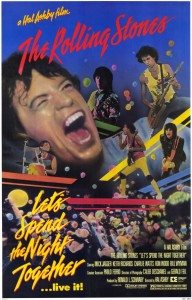

Filmed in 1981 over three nights — one at Sun Devil Stadium in Arizona and two at the Meadowlands in New Jersey — Let’s Spend the Night Together seems pretty straight forward as it begins: director Hal Ashby captures the Rolling Stones, live on-stage. If you were a Stones fan, and you were alive in the early ’80s, you probably went to see this concert film and thought: yep. Those guys sure can play that there rock and/or roll.

Filmed in 1981 over three nights — one at Sun Devil Stadium in Arizona and two at the Meadowlands in New Jersey — Let’s Spend the Night Together seems pretty straight forward as it begins: director Hal Ashby captures the Rolling Stones, live on-stage. If you were a Stones fan, and you were alive in the early ’80s, you probably went to see this concert film and thought: yep. Those guys sure can play that there rock and/or roll.

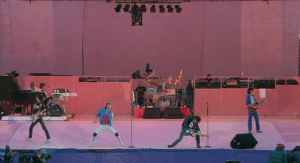

You might, back then, not have snickered at the fashion choices, perhaps because you were also wearing a tight, sky blue leather jacket and lace-up pants. You mightn’t have raised an eyebrow at the giant, peach, abstract sets. Likely, you also wouldn’t have commented on how young Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ron Wood, Charlie Watts, and Bill Wyman looked — because, to you, those guys were fucking old. In 1981, the Rolling Stones were celebrating their 20th anniversary as a band.

Not like today, when they’re older than your grandpa’s collection of taxidermy badgers and still playing stadium concerts.

But I did not watch Let’s Spend the Night Together in the 1980s. I saw it for the first time now, in 2014. And now, it is more than a time capsule of what it must have been like to see the Stones tour to promote Tattoo You. It is a window into what it was like to be a flea in the biggest flea circus around.

Ashby’s cameo appears to these lyrics: ‘Nobody will know, when you’re old. When you’re old, nobody will know.’

I love the Rolling Stones. It may be unpopular to say so, but I think side two of Tattoo You, the album this tour heavily features, is among their best work. I am equally enamored of Hal Ashby. It may be even less popular to say so, but his 80s films have merit. Or some of them do. After his heyday of Harold & Maude, Shampoo, Being There, and others, Ashby made films that disappeared with nary a trace. This was the last of his films left for me to see.

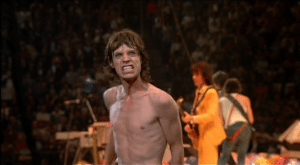

Let’s Spend the Night Together begins backstage, but that’s an anomaly; almost all of the film takes place on-stage. Mick Jagger comes out to greet Sun Devil Stadium. What impresses almost immediately is not the magnitude or the roar of the crowd — it’s the size of the stage these few, well-aged men must animate.

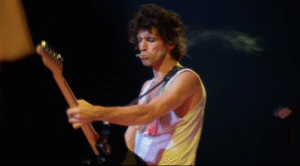

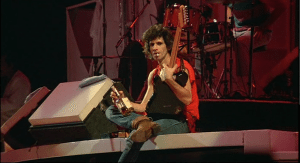

Many have commented over the years on the energy Mick Jagger brings to his performances. Here, that expenditure seems to tax him. While Ron Wood strolls about and Keith Richards mimics a marionette, Jagger runs back and forth across acres of terrain, flinging his limbs to the wind and thrusting himself into orbit. As they roll through Under My Thumb, Let’s Spend the Night Together, and Shattered it slowly dawns on me: doing this is his job.

Many have commented over the years on the energy Mick Jagger brings to his performances. Here, that expenditure seems to tax him. While Ron Wood strolls about and Keith Richards mimics a marionette, Jagger runs back and forth across acres of terrain, flinging his limbs to the wind and thrusting himself into orbit. As they roll through Under My Thumb, Let’s Spend the Night Together, and Shattered it slowly dawns on me: doing this is his job.

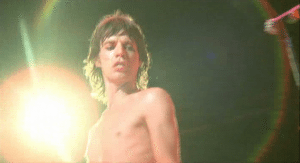

In the day-lit, outdoor hours early on in the show, I do not watch and wish I was there in the audience; I gain respect for what it must be like to work as Mick Jagger works. He performs for us. It isn’t the exuberant joy of taming sound into music, it is the invocation of complex sigils and spells in the attempt to entrance over 70,000 people. This is his job. This is work, and hard work at that.

During Neighbors and Black Limousine, I step farther back. Hal Ashby reportedly directed one of these nights from a cot with an IV in his arm (exhaustion say some, drug abuse say others), but which elements here can we attribute to him? Caleb Deschanel and Gerald Feil handled the cinematography, and their control over the camera department draws no complaints. When the film was released, critics lauded the beauty of the film but today it seems distant and choppy. Is that Ashby’s influence or technical realities intruding? The latter most likely.

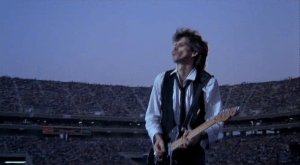

Ashby didn’t edit the picture, either. That was Lisa Day, who went on to edit the best concert film ever, Stop Making Sense, just a few years afterward. This one starts awkwardly, but Day’s editing picks up as night falls and the band builds up steam. In the early numbers, cuts create incongruities as we swap between cameras. After the sixth track, however, Just My Imagination, my adoration of the Rolling Stones’ sound begins to overcome my critical distance. I could watch Keith play all day.

Ashby didn’t edit the picture, either. That was Lisa Day, who went on to edit the best concert film ever, Stop Making Sense, just a few years afterward. This one starts awkwardly, but Day’s editing picks up as night falls and the band builds up steam. In the early numbers, cuts create incongruities as we swap between cameras. After the sixth track, however, Just My Imagination, my adoration of the Rolling Stones’ sound begins to overcome my critical distance. I could watch Keith play all day.

Mick now looks like a semaphore flag; Keith like a puff of smoke. Elder statesmen Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts duck the camera, or look away disinterested. For them, too, this is simply a day at work. The band plays a pair of covers — Twenty Flight Rock and Let Me Go — and it’s intentional, where we are and how we feel. It’s Hal Ashby working with the Rolling Stones to show you.

Let’s Spend the Night Together is your chance to understand what it’s like to perform in a band this outsized, not what it’s like to see them perform. Mick Jagger abandons the stage to move through the crowd. Even flanked by security he looks like an ant amid an army of spiders. Seventy-thousand people reach out to smear his preposterous fashion and he jerks and wiggles through them, on schedule, clocking in. Here’s Hal Ashby, finding the challenges that makes his subjects fascinating.

During Time Is on My Side, shots of the band are intercut with old snips of stock footage — them performing as younger men, larking as lads. This swing through nostalgia takes a left turn, though. First, without comment, we see shots of Brian Jones, who was muscled out of the Stones and shortly thereafter died — another man who struggled with narcotics. This is followed by shots of the pope, and war, including a head on a stake.

During Time Is on My Side, shots of the band are intercut with old snips of stock footage — them performing as younger men, larking as lads. This swing through nostalgia takes a left turn, though. First, without comment, we see shots of Brian Jones, who was muscled out of the Stones and shortly thereafter died — another man who struggled with narcotics. This is followed by shots of the pope, and war, including a head on a stake.

A real head. On a real stake. It is Viet Nam, and the band is still playing Time Is on My Side but the sun is setting. We’ve seen in clips young Mick jump about in a clown costume, and the sickly smile of Brian Jones, and a head on a stake. Of the three, I’d say Jagger’s the one who managed to keep time on his side. The other two, not so much.

Beast of Burden sinks us into dusk and, as always with rock shows, night somehow unlocks hidden energy. After Waiting on a Friend, the show transplants to East Rutherford, indoors, in November. Gone is the open-air expanse. Now, as the Stones play the Miracle’s Going to a Go-Go, Ashby gives us a sped-up sequence of the Meadowlands stage being assembled. Instead of abstract art flanking an impossibly large stage, here it’s a complex series of oblongs that revolves, so each seat gets an equally fine view of Mick’s ribs.

Indoors it feels more intimate. You’ve lived with the Rolling Stones as they played through the close of day, and now it is another day, another state, another crowd, and they’re still going. Each song springs into the next without pause — a choice in direction and not a reflection of reality. This is their life, it says. Get up. Play the songs. Give the people what they want. Do your job. Fittingly, the tracks they course through here are You Can’t Always Get What You Want and the Keith Richards number Little T&A.

Indoors it feels more intimate. You’ve lived with the Rolling Stones as they played through the close of day, and now it is another day, another state, another crowd, and they’re still going. Each song springs into the next without pause — a choice in direction and not a reflection of reality. This is their life, it says. Get up. Play the songs. Give the people what they want. Do your job. Fittingly, the tracks they course through here are You Can’t Always Get What You Want and the Keith Richards number Little T&A.

Mick is in a new costume, always. This time a green football jersey as he continues to vamp through Tumbling Dice and She’s So Cold, which takes us back to Arizona. The speed dials up further, now with quick cuts through a frenzy of days and shots and arduous is how it feels. Unending. As good as the Rolling Stones sound — and they do sound good — I want to them to stop, just for a moment, to breathe.

But they don’t. The show — shows, really — presses on into better and better performances. All Down the Line, Hang Fire, Miss You, and Let it Bleed. Mick looks angry, Keith looks like he’s come to fix the sink, Wood is just joshing, Wyman resembles a cardboard stand-up, and Watts looks like he’s running sums in his head.

But they don’t. The show — shows, really — presses on into better and better performances. All Down the Line, Hang Fire, Miss You, and Let it Bleed. Mick looks angry, Keith looks like he’s come to fix the sink, Wood is just joshing, Wyman resembles a cardboard stand-up, and Watts looks like he’s running sums in his head.

The workday’s almost done, now. You can see it in the way the sweat soaks and runs. Start Me Up again turns up the juice and surely the well must soon run dry? For Honky Tonk Women, they call in the reserves — an endless line of women in frilly frocks and French maid outfits to fill the stage. It would seem a boy’s dream, but Mick’s too busy to gawk — not even at Jerry Hall, who’s among them, with Charlie Watts’ wife Shirley, and oddly, what appears to be Ron Wood’s tiny daughter looking like Little Bo Peep.

The show closes with Brown Sugar, Jumpin’ Jack Flash, and, as you rightly guessed, Satisfaction. As they close with their earliest and most enduring hit, balloons cover the stage. For a few moments now, and scattered throughout, you see the joy. Yes, this is a job. Yes, it’s incredibly hard work.

But you’re in the Rolling Stones.

But you’re in the Rolling Stones.

You’re Keith Richards and you’ve got the guitar’s skeleton key. You’re Mick Jagger and you’ve got a choir of righteous power packed in your ghostly, anorexic frame. You’re going to do this again, and again, and again.

And we’re grateful.

Yes. Beautifully put.

Glad you agree.