You know what the only thing better than being in a gang fight is? Not being in a gang fight. Watching a gang fight, now that’s the ticket. Full of hot-heads and back-stabbers, thieves and killers, gangs are made up of exactly the sort of people you’d love to see die in a mutual bloodbath.

But what if they don’t want to fight? What if you’ve got two gangs, they hate each other, they’re out for blood, but they’re lying low, biding their time, playing it smart? You have to stir things up, is what. You, an outsider, on neither side, but available, for a price, to either, have to make each believe you’re working for the other, when the only person you’re working for is yourself. It’s best if you have no name, no past, no future, and find grim amusement in bringing out the worst in people.

For this week’s Mind Control Double Feature, we find ourselves embroiled in a classic story spanning cultures, time, and at least one lawsuit.

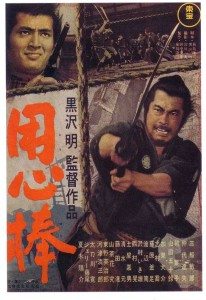

Yojimbo (1961)

Our story begins with American hard-boiled noir author Dashiell Hammett’s 1931 novel, The Glass Key, or possibly his 1929 novel, Red Harvest, or maybe some of both, or maybe most of all the wonderful 1942 movie adaptation of The Glass Key, starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.

Our story begins with American hard-boiled noir author Dashiell Hammett’s 1931 novel, The Glass Key, or possibly his 1929 novel, Red Harvest, or maybe some of both, or maybe most of all the wonderful 1942 movie adaptation of The Glass Key, starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.

Which novels and movie—especially the movie—are the inspiration for the Coen Brothers’ masterpiece, Miller’s Crossing (seriously, if you can get your hands on The Glass Key, watch it before watching Miller’s Crossing—where else but Hammett could they have gotten such lines as, “What’s the rumpus?”).

Fifty years ealier, Hammett’s work inspired Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, which despite its noirish source material he made as something of an ode to American westerns by the likes of John Ford, with their wide open vistas and windswept, lonesome towns.

Instead of a gunslinger (or as in Hammett, a nameless, pistol-packing “op” (as in “operative”)), Kurosawa goes with a sword-swinging ronin, i.e. a masterless samurai, roaming free, with nowhere to go and no one to serve.

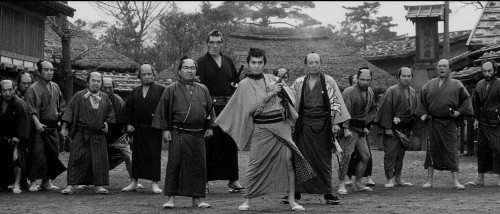

Yojimbo opens in the middle of nowhere. The ronin in question, Sanjuro, played by Kurosawa regular and contender for biggest cinematic bad-ass of all time, Toshiro Mifune, comes to a fork in the path. He tosses a stick into the air, lets it fall and point the way.

The way leads him to a town controlled by two warring factions. The innkeeper tells him to hurry along, but Sanjuro, learning of Seibei and Ushitora, the nasty gangleaders, suggests they’d be better off dead, and sticks around to see what he can do about it. In short order, Sanjuro shows off his prodigious skills as a swordsman and hires himself out to Seibei. After which Sanjuro goes about playing one side against the other, lying to both, and causing no end of trouble, until he makes an unfortunate error, and his two-timing ways are discovered. He’s beaten next to death.

Upon recovering, he takes it upon himself to finish things. It ends with a classic, western style showdown in the middle of town.

Because Kurosawa is Kurosawa—i.e., a genius—he outwesterns the westerns that inspired him and creates in Yojimbo one of the greatest mythic anti-hero easterns of all time (easterns, right? Who’s with me?). Not that Sanjuro isn’t the hero of the piece. He’s the man you root for. But he’s not exactly a guy with the purest motives.

It’s shot in beautiful widescreen black & white and deserves to be seen, if not in 35mm in a theater, on a blu-ray on the biggest TV you can steal from Best Buy. (And if you convince them Costco stole it, why just imagine the war you can start.)

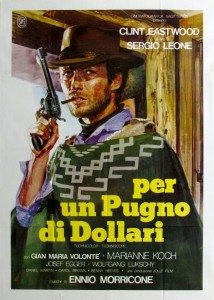

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Three years later, along came Italian director Sergio Leone with a plan to reinvent the Italian western by ditching the then-tired Hollywood conventions and shooting it like some kind of mad opera. What better way to achieve his goal than by remaking a Japanese samurai movie?

Three years later, along came Italian director Sergio Leone with a plan to reinvent the Italian western by ditching the then-tired Hollywood conventions and shooting it like some kind of mad opera. What better way to achieve his goal than by remaking a Japanese samurai movie?

For reasons I am unclear on, Leone didn’t bother acquiring rights to the remake, and for reasons yet more mysterious, Leone’s claim that his movie isn’t based on Yojimbo are to this day taken seriously (by some). Leone and his defenders have argued that A Fistful of Dollars is based on an 18th century play by Carlo Goldoni, Servant of Two Masters, where the story of one man playing two sides against each other originated. Hammett and Kurosawa, they claim, based their work on the same play.

This almost sounds reasonable until you actually watch the movies in question. As Kurosawa wrote in a letter to Leone, “Signor Leone—I have just had the chance to see your film. It is a very fine film, but it is my film.” It’s not that the two movies have similar stories, it’s that Leone copied Yojimbo scene for scene. It is literally the same movie. A lawsuit followed. Leone settled.

The amazing thing about all of this is that even though Leone outright stole his movie from a genius of cinema, even though it’s a scene for scene remake, A Fistful of Dollars stands on its own as a brilliant movie. Kurosawa wasn’t just being polite. If you watch these two back to back—as you are hereby required to do—it’s like watching two completely different movies that are exactly the same. Strange but true.

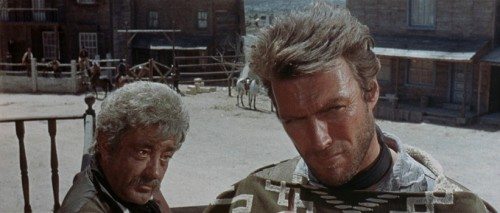

Clint Eastwood wasn’t Leone’s first choice to star, but he couldn’t have picked anyone better. Eastwood was then known as a TV western actor. A Fistful of Dollars made him a star. It’s one of his best movies. He squints and chews a cigarillo and wears a hat. That’s his whole performance, and it’s a work of art.

Leone’s style is all close-ups and wide shots and little in the way of dialogue. Operatic, basically. Genius composer Ennio Morricone supplied the music, the one element that tops Yojimbo, itself blessed with what was at the time a very unusual score for a Japanese movie. Morricone’s score is beautifully weird, featuring—alongside horns, strings, and electric guitar—whistling, chanting, whips, and gunshots.

As for the story? See above. Clint is the Man With No Name. He comes to town, and pretty soon everyone’s dead.

It’s not often a remake rivals (or betters) the original. When it happens, it’s inevitably because of how different one is from the other. Yojimbo turned into A Fistful of Dollars is a unique case (can you think of another?). One movie that is two movies, and both are great.

Now this double feature is highly enjoyable and I find it an interesting timely coincidence, that I would undergo the same double viewing at home about 4 weeks ago. I first watched Yojimbo as part of a personal Kurosawa revival and after reading about its source material and the intended homage to American western, I had to scour for that dusted copy of A Fistful of Dollars to follow suit. This double viewing becomes so extremely interesting when realising that despite the apparent completely different feel and look of both films and the cultural tradition and aesthetics they are hailing, they do have so many elements of basic idea, vital plot elements and structural similarities. Like you, I’ve always enjoyed Kurosawa’s camera, the visual narrative. Yojimbo might not be his very best creations, but it certainly offers newness to an old theme and beautiful, beautiful scenes and scenarios. Not sure I have anything useful to add to Fistful of Dollars besides maybe needing them, but I am glad you pitched for those two classics.

Yep, it’s fun to watch them close together and be amazed at Leone’s balls, and then be further amazed at how seeing one doesn’t detract from the other.