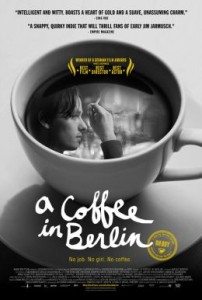

Some days all you want is a cup of coffee, and you can’t even get that much right. So it is for Niko (Tom Schilling), a twenty-something Berliner (not a jelly donut) whose life has been going nowhere in the newish German movie, A Coffee In Berlin. Or so it’s been named for its U.S. release. It was originally released in 2012 with the name Oh Boy!, which despite being English sounds better in Germany than it does here. Name a movie Oh Boy! in the U.S. and it had better be full of song and dance.

Some days all you want is a cup of coffee, and you can’t even get that much right. So it is for Niko (Tom Schilling), a twenty-something Berliner (not a jelly donut) whose life has been going nowhere in the newish German movie, A Coffee In Berlin. Or so it’s been named for its U.S. release. It was originally released in 2012 with the name Oh Boy!, which despite being English sounds better in Germany than it does here. Name a movie Oh Boy! in the U.S. and it had better be full of song and dance.

A Coffee In Berlin is not a musical. It’s a day and a night in the life of Niko, during which nothing much at all happens. Yes, it’s one of those movies. The nice thing about A Coffee In Berlin is that it’s one of those movies that works. It’s shot beautifully in black & white, giving Berlin the Woody Allen Manhattan treatment (including a couple of old jazz numbers on the soundtrack), though it has far more in common with early Jim Jarmusch than it does with Allen’s movies.

Newcomer Jan-Ole Gerster wrote and directed it, his first movie, a thesis project for film school, and though it has a certain film school feeling, I wouldn’t have guessed that it’s a director’s first movie. It feels confident in its low-key vibe.

Nothing that happens to Niko is particularly novel. He half-assedly ends a thing with a girl, is denied a driver’s license by an obnoxious psychologist, hangs out with his one friend, a never-made-it actor (Marc Hosemann), is given meatballs by his neighbor, runs into a girl (Friederika Kempter) he knew in grade school, sits in a drug-dealer’s grandmother’s electric-powered easy-chair. That sort of thing.

This is a movie where a scene about sitting in an easy-chair is the emotional high point.

His actor friend knows a famous actor. They visit the set of his new movie, in which he (the famous actor), plays a Nazi in WWII—but a good Nazi, one with a heart, who only wants to be with his Jewish girlfriend. Wisely, Niko makes no comment.

The girl Niko knew in school used to be fat. Seems he and everyone else teased her mercilessly, before she tried to kill herself and was sent to fat-kid-boarding-school. But she’s thin now and totally over it. Or so she claims. Often. She’s the one whose performance art dance piece we see later on.

And so on. Niko couldn’t be more unconnected from the world around him. He floats through life, but life keeps poking at him, trying to draw him back in. I suppose one might compare this to the so-called “mumblecore” genre of American movies, low-budget flicks where twenty-somethings wander around, attempt to have relationships, and articulate their feelings poorly. The major difference is while those movies tend to be insufferable and dull, A Coffee In Berlin is entrancing. It feels like real life–like a sad real life–and yet it works as a movie. Is it a bit too pat with its ending? Which I won’t spoil? I almost thought so. And then I didn’t.

No new ground is broken in this story, but not everything needs to be new. It only needs to be good. A Coffee In Berlin does something deceptively simple unusually well. What more need be said? Just this: you should see it.

Oh, I hear and obey … Cinema in Berlin? I might just hop over for the right feel