As far as depicting a world gone completely tits up goes, you’d be hard pressed to top the work of Australians. There is something overwhelming, and terrifying, about the vast emptiness of the place; it makes it easy to picture what it would be like if the Outback slipped its leash for good. If you were surrounded by endless, maddening nothing.

As far as depicting a world gone completely tits up goes, you’d be hard pressed to top the work of Australians. There is something overwhelming, and terrifying, about the vast emptiness of the place; it makes it easy to picture what it would be like if the Outback slipped its leash for good. If you were surrounded by endless, maddening nothing.

And wombats.

I, of course, mean this as a compliment. I lived for years in Australia. There is nowhere better to stare into the void, excepting perhaps a cinema showing an Adam Sandler film.

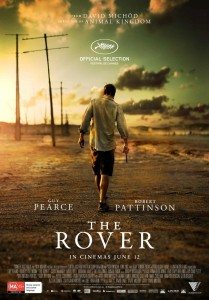

This brings us to David Michôd’s new film. The Rover takes the savageness of Mad Max, the nasty tension of The Proposition, and the unhinged panic of Wake in Fright and blends them into something powerfully caustic and more than a bit strange. Much of it is hard to forget. Some of it you might wish you had.

The Rover takes place, as opening titles announce, ’10 years after the collapse.’ That’s about it for backstory. Guy Pierce plays Eric, who appears wholly animated by furious resentment. A trio of men wreck their car in the South Australian nowhere. They steal Eric’s in its place. He goes after it with the intensity of a dog attack.

These men, the thieves — including Scoot McNairy (of Monsters) as Henry —have left behind Henry’s wounded brother, Rey, in their fear and haste. Rey is played by Robert Pattinson, who imbues the part with a vociferous naivety, as if his mind had yet to congeal.

As Eric’s hostage, or companion, or reflection, Rey leads them towards the missing automobile across the plains of death.

For in The Rover many people die. Most of them murdered for almost no reason or for reasons so scant it would almost be better if there were no reason at all. Many of them eat their death from the anger in Eric’s eyes and the violence in his gun. It reminded me, more than anything, of how reading Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian felt.

But what is The Rover about? What, as the opium-submerged woman called Grandma (Gillian Jones) asks, is your name? What’s so important about this car?

Eric does not, cannot answer. All he can do is rampage and absorb the tears that threaten to storm him. He is rage born of pain. Guy Pierce — whose face is cradled in long, slow takes — gives this all he’s got. It is beyond plenty. So, too, provides Pattinson. In his care, Rey begins as one thing and becomes another, like grain warps and stews into alcohol. There may have been times Pattinson lost control of the subtlety of his characterization, but those were counterbalanced by other moments sharply honed.

Much of The Rover comes in koans and glimpses, aided by the kind of cinematography that makes you cherish the gruesome and frightful. Slow movements, a flash of rich color amid deep dust, the catharsis of utter loss. Perhaps even more than the look of the film, however, its score serves to trap you in its chaotic, untethered land. Some musical elements evoke the Noh theater, others are the kind of minimalist electronica that accompanies the dawn. Colin Stetson ravages a saxophone and then there’s some R&B pop to remind you of just how lost we have become.

Much of The Rover comes in koans and glimpses, aided by the kind of cinematography that makes you cherish the gruesome and frightful. Slow movements, a flash of rich color amid deep dust, the catharsis of utter loss. Perhaps even more than the look of the film, however, its score serves to trap you in its chaotic, untethered land. Some musical elements evoke the Noh theater, others are the kind of minimalist electronica that accompanies the dawn. Colin Stetson ravages a saxophone and then there’s some R&B pop to remind you of just how lost we have become.

There were many scenes in The Rover that I’m sorry I can’t watch again right now. As Eric struggles, and confesses, and kills, the words Michôd places in his mouth come out exactly. In the end, though, I leave questioning.

About the ending, which, fair warning, I will now reveal:

It turns out, after the carnage and killing, casual or not, that Eric wants the car because in its boot lies the corpse of his dog. The Rover, one might surmise. When everyone is dead, including those Eric loved due to Eric’s own actions, he pulls the reclaimed automobile to the side of nowhere and pulls out his shovel.

Is he burying his past? Is Michôd saying something about what man can take, or give, or forgive?

I do not know what The Rover means, if anything. It’s bleakness is wonderful, with endless dust and blood and hurt, but to have it all come down to a dead dog felt perverse, almost comic.

If there is a statement there, about humankind, or about loss, I am unsure of its meaning. It’s hard not to think back to Mad Max, or Wake in Fright, and wonder what it is that these near-apocalyptic Australian films share. Why they so excel at breaking man down. And what we can learn from that.