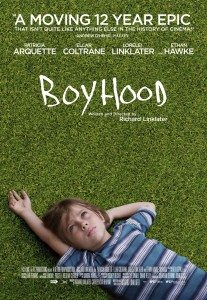

Richard Linklater’s Boyhood has received a lot of critical acclaim. People have made a big deal about the fact that the film was shot over a dozen years, using the same actors to tell the story of a boy growing into a man.

Richard Linklater’s Boyhood has received a lot of critical acclaim. People have made a big deal about the fact that the film was shot over a dozen years, using the same actors to tell the story of a boy growing into a man.

Fair enough. That’s a fairly incredible feat; the more-so for its resulting in such a successful piece of cinema. The idea of working on any artistic project for over twelve years and having it come out coherent is testament to Linklater’s consistency of vision.

It is not the scope of the filmmaking that makes Boyhood incredible, however. It is what that scope does to your brain — and no matter how many articles you read about it, you’re going to have to watch the film for yourself to experience it.

Watching Boyhood will likely tarnish your favorite films. It will make even verité-style feature films feel as fabricated as Brigadoon or Labyrinth. It will nail your skull with an entirely new understanding of what film can be: a time machine, a psychotropic narcotic, a memory you mislaid.

Here’s how stunning Boyhood is. When it ended, after I had spent nearly three hours entertained, and engaged, and feeling slightly unsteady, I found myself reading the film’s credits, wondering who had played Mason Jr. as a child.

Here’s how stunning Boyhood is. When it ended, after I had spent nearly three hours entertained, and engaged, and feeling slightly unsteady, I found myself reading the film’s credits, wondering who had played Mason Jr. as a child.

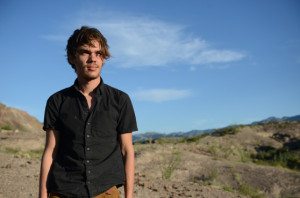

It was Ellar Coltrane. He played Mason at six, and at twelve, and at eighteen, and for every moment in between. And you’re saying, ‘Duh, of course, that’s the whole point of the experiment’, but knowing something intellectually and accepting it emotionally can remain distinct. The fact that all of the characters in Boyhood were played by the same cast members over a dozen years — watching the results of this play out before you — feels like breathing water, or going to bed tonight and waking up yesterday. It corrupts the logic of what your brain expects to be possible.

You cannot possibly watch real people grow from children to adults in under three hours. To see that occur would be to live an experiment of Einstein’s design.

It would be — it is — beautifully insane.

Boyhood scraped a solidified layer of concrete off my consciousness. When I was a boy, I was a boy and that was ages ago. Then I watched Linklater’s film and remembered — felt — how the young me evolved into what still remains me via a normal, progressive, gentle process. A process without manufactured drama, or three acts, or even that many memorable moments percentage-wise. Just a series of heartbeats and layers of learned familiarity.

Boyhood scraped a solidified layer of concrete off my consciousness. When I was a boy, I was a boy and that was ages ago. Then I watched Linklater’s film and remembered — felt — how the young me evolved into what still remains me via a normal, progressive, gentle process. A process without manufactured drama, or three acts, or even that many memorable moments percentage-wise. Just a series of heartbeats and layers of learned familiarity.

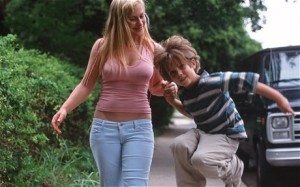

Linklater’s script for Boyhood is a marvel of authenticity; it is hard for me to believe it was not completely improvised. Each expression in it sounds as natural as any exhalation. Being shot in the exact period each scene encapsulates couldn’t have hurt — this is what song was really on the radio; this is what my daughter Lorelei (playing Mason’s older sister Samantha) just said to me; this is really happening around us. Still. Anyone who wins an award over this piece of screenwriting should feel ashamed.

The story simply rolls. The drama is only to grow up. And no one, not Linklater and not Coltrane, could guarantee that Mason Jr. would succeed in that dramatic arc. As it happened, you’d be hard pressed to find an actor who would appreciate with as consistent gains in value as Ellar Coltrane. The other cast members, both leads and supporting, keep pace without any signs of strain. Watching Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette and Lorelei Linklater age is no less astounding than watching Coltrane grow. Ethan Hawke, when they started filming, was just coming off of awards for Training Day.

The story simply rolls. The drama is only to grow up. And no one, not Linklater and not Coltrane, could guarantee that Mason Jr. would succeed in that dramatic arc. As it happened, you’d be hard pressed to find an actor who would appreciate with as consistent gains in value as Ellar Coltrane. The other cast members, both leads and supporting, keep pace without any signs of strain. Watching Ethan Hawke and Patricia Arquette and Lorelei Linklater age is no less astounding than watching Coltrane grow. Ethan Hawke, when they started filming, was just coming off of awards for Training Day.

That’s how long ago they started making this movie.

They were younger. They are now older. All of those instances, from beginning to end, are equally them.

I cannot tell you to watch Boyhood because it is a brilliant film in the way that other films may be brilliant. It is well (and daringly) written, well acted, and shot naturalistically. All true. Instead, I insist you watch Boyhood because it will scrunch your brain into a tiny ball, wrap it in gelatin, and make you swallow it like a mystery pill. It is not what the film is that’s incredible; it’s what the film does.

Watching Boyhood is like falling off a cliff of time. It is like having your brain blown like a bubble. It is fiction, but more real than most memories.

Watching Boyhood is like falling off a cliff of time. It is like having your brain blown like a bubble. It is fiction, but more real than most memories.

It is profound. Here, before you, in just 166 minutes, is the gradual change that makes life. That transmutes youth into you. Here is where you came from.

I watched Boyhood sitting beside a college-age couple. When it ended, I wanted to ask them how it made them feel — to see their generation so exploded and compacted — but I couldn’t.

They were making out.

All that good shit is wasted on youth.

you’re still young, just not any more.

Looking forward to the this.