Richard Linklater likes playing with time. Of course all filmmakers manipulate time, that’s what movies do, but Linklater takes a longer view than almost anyone else. In his Before series, he hooks up with actors Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke every nine years to tell the ongoing story of their relationship. It’s fascinating to see how the actors have aged in the interim, and what that brings to their characters. In his new movie, Boyhood, Linklater does something even stranger by shooting a movie over a twelve year period centered on the childhood of a boy, played by Ellar Coltrane, as he grows from seven to eighteen.

Richard Linklater likes playing with time. Of course all filmmakers manipulate time, that’s what movies do, but Linklater takes a longer view than almost anyone else. In his Before series, he hooks up with actors Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke every nine years to tell the ongoing story of their relationship. It’s fascinating to see how the actors have aged in the interim, and what that brings to their characters. In his new movie, Boyhood, Linklater does something even stranger by shooting a movie over a twelve year period centered on the childhood of a boy, played by Ellar Coltrane, as he grows from seven to eighteen.

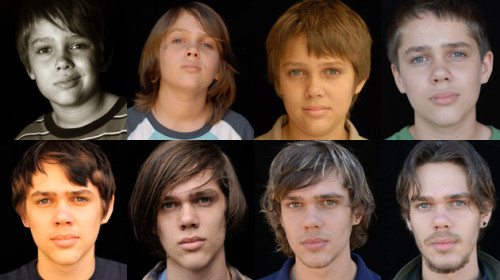

What’s immediately stranger is watching Coltrane, as Mason Jr., age before our eyes (along with everyone else in the cast). With the Before movies, we have to wait nine years between films for the actors to age. Each film is a snapshot of where there are, akin to Michael Apted’s documentary Up series, which catches up with a group of Britons every seven years. With Boyhood, Linklater did the waiting for us, shooting about fifteen days once a year for twelve years. Scene by scene, Mason Jr., his sister, Samantha (played by Linklater’s daughter, Lorelei), his divorced parents, Olivia and Mason Sr. (Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke), grow up, and it’s fascinating, their aging, almost irrespective of whatever else they’re doing.

You could fairly call Boyhood a gimmick movie. But the thing of it is, the gimmick works.

We meet up with Mason, his sister, and his mom living in a Texas town. She’s a young single mom, having a hard time of it. We don’t see scenes so much as moments. Mason at school, riding his bike, play-fighting with his sister, and overhearing his mom fighting with her current boyfriend.

They move to Houston to be near Olivia’s mother, and it’s here Mason Sr. returns from a sojourn in Alaska, takes the kids out, he’s probably stoned, he’s like a magical elf of a father, turning up to play, then leaving just as fast. Hawke is wholly believeable as a rootless man unprepared for any form of responsibility.

Olivia goes back to school and marries a professor, who turns out to be an angry drunk. We don’t see the wedding, nor her next wedding, nor Mason Sr.’s eventual wedding. We don’t see a lot of what you’d think would be the obvious scenes in the childhood of a boy.

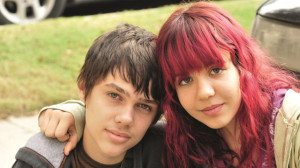

There’s no first alcoholic drink, though he drinks at one point. His first time? We don’t know. His first kiss? Losing his virginity? Nope, at a certain point he talks to a girl, and later he’s dating her, and later he’s in bed with her, but it’s clearly not their first time. It’s like the movie consists of the iconic scenes you know have to be in it, yet still avoids the most obvious ones. The ones it includes are always powerful, written and acted with unaffected naturalism.

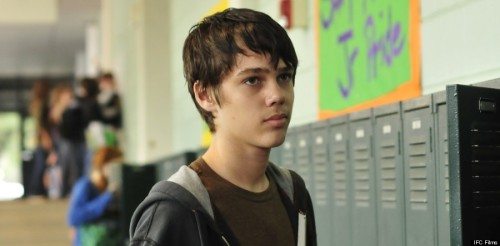

Another curious aspect of the movie’s structure is its lack of typical drama. It’s more that we’re presented with iconic moments and left to imagine their implications and all that surrounds them. So for example in middle school Mason is in the school bathroom. A couple of tough guys see him, shove him, threaten him, and leave. Mason doesn’t really say anything. Just takes it in, as do we. There’s no follow-up, no fight later on. Because later on is a year later on, and something else is happening.

What’s strange about this is how well it works. The fact that we’re watching Mason literally age before our eyes makes unnecessary typical dramatic sequences. Which isn’t to say there’s no drama. There are plenty of tense scenes. I think what it comes down to is, as above, the lack of immediate follow-up. We’re shown intense moments, one after the other, year after year, and that’s all we need, it turns out. It creates an unusual kind of flow that carries you with it.

It reminds me of those YouTube videos that crop up now and again where someone takes a photo of themselves every day for ten years, then strings them together in a four minute rush of aging. Only in this case it’s not photos, it’s scenes from a life played out one after the other.

The movie is long, though, at 166 minutes. After a first half that’s nothing less than enthralling, I felt it dragging for awhile. But it manages to pick up again, and as you feel it nearing the end, with Mason finally leaving home for college, you’re waiting to see what perfect moment, what perfect line, the movie ends on. Linklater finds a good one.

Speaking of good finds, what luck (or prescient genius?) to find a kid like Ellar Coltrane, who grows into his character as the movie progresses. He’s a natural as a kid, then turns into a real actor before our eyes. His sister outshines him in the early going, when the movie is less “boyhood” than “familyhood,” but slowly the focus devolves onto Mason, and Samantha is sidelined.

Also unlike the Before series, Boyhood isn’t especially talky. Mason is very much a reactive character. He watches and listens. Not until his teen years does he begin to speak up. He’s got to charm girls, after all. But he doesn’t get in fights, doesn’t get in trouble, doesn’t drive the story in any sense but the largest one: he grows up.

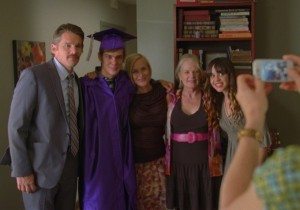

His parents do, too. In one sense it’s more their story than his. They’re living lives full of drama and turmoil, and he’s just watching, waiting for his life to begin. When it does, the movie ends. Olivia raises two kids on her own, goes through three husbands, gets a degree, and at 41, single, watches her youngest kid leave for college. Mason Sr. screws around for years, showing up only sporadically, before remarrying into a god-and-gun-loving Texan family and having a new baby. As he reaches 40, he’s finally ready for fatherhood.

Mason never fights with either parent, outside of a slight argument or two. He’s an observer. He watches how adults in this world behave, and we watch him. It’s gripping. There’s never been a movie quite like this. It combines the documentary reality of people aging with the story-telling of a fiction film. It creates the same sad, nostalgic, hopeful, wistful feeling you get looking at a family photo album of yourself as a kid.

Does that make Boyhood the most profound movie ever made? Reading some of the praise it’s being showered with, one would almost think so. I wouldn’t go quite so far. It’s unique and, on the whole, lovely, and that’s plenty. Expect it to win many an award come the end of the year. Should we also expect a sequel? Knowing Linklater, why not? Wait ten years, then film for another twelve? I don’t see how he could resist.

I will read this tomorrow, after I’ve seen Boyhood, hopefully tonight.

I’m having a hard time putting how I feel about this film into words. It’s not like anything else. Despite everything, I still got confused when there was only one credit for Mason at the end. How could one actor play that part through all of those ages?

It was all him. Them.

Boyhood is like experiencing your own youth disappearing.