Each generation gets its own film, one picture that encapsulates what it feels like to be a teenager at that particular time. Rebel Without a Cause captured the moral decay that swamped youth in the 1950s. Half a century later, in the 2000s, Mean Girls presaged the moral decay that swamped Lindsay Lohan.

Teenagers don’t change that much.

Of those of us from the long past class of 1990, many would point to the work of John Hughes — specifically that ode to the insecurities that plague potential adults, The Breakfast Club, as the paragon. While I love me some Breakfast Club, that film didn’t encapsulate my late-80s high school angst. It’s charming but a tad too neat.

For me, the siren song was always Michael Lehmann’s Heathers. This film is not charming, not neat. It’s rather just as uncomfortable as days spent in high school. Where The Breakfast Club took all that was wrong with young adulthood and made it feel a little more right, Heathers did just the opposite. It lit the fuse on the decay of the Ronald Reagan era; it reflected the catharsis of the crumbling Soviet Bloc; it dissected the nihilism of being seventeen in 1989.

For me, the siren song was always Michael Lehmann’s Heathers. This film is not charming, not neat. It’s rather just as uncomfortable as days spent in high school. Where The Breakfast Club took all that was wrong with young adulthood and made it feel a little more right, Heathers did just the opposite. It lit the fuse on the decay of the Ronald Reagan era; it reflected the catharsis of the crumbling Soviet Bloc; it dissected the nihilism of being seventeen in 1989.

Until last weekend, I hadn’t watched Heathers in over twenty years. It holds up perfectly, remaining just as raw and shocking and darkly comic as I recalled. Heathers gets its nasty little fingers inside your knickers, making you squirm in way that’s delightfully uncomfortable. It might as well have been made last week — except instead of trying to shock you with gross-out bodily function humor like today’s lame teen comedies do, it genuinely rubs you where you’re raw.

It turns out that none of those childhood wounds have healed; they’ve just been passed down to a new set of proto-adults.

Much like wherever you went to school, Westerberg High in this film is dominated by Heathers. Heather Chandler (Kim Walker) is queen bee, a vicious beauty with the soul of a succubus. Bound in her gravity field follow Heather Duke (Shannen Doherty), a brow-beaten bulimic who unsubtly studies Moby Dick, and Heather McNamara (Lisanna Falk), a cheerleader of challenged self-worth. And then there’s Veronica Sawyer (Winona Ryder) — not exactly a Heather, but very much one just the same. As she admits near the start, “I don’t really like my friends,” but that doesn’t keep her from championing their cruelty and superiority anyway.

Winona, like much of the cast, was a bona fide teenager, just 16 at the time of filming.

Winona, like much of the cast, was a bona fide teenager, just 16 at the time of filming.

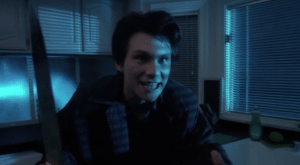

Into this world of keenly caricatured football players and stoners and geeks comes J.D. (Christian Slater), a black-clad rebel. J.D. catches Veronica’s eye and together they start killing people. Because that’s what high school is like.

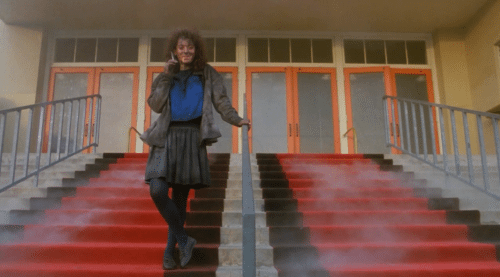

High school isn’t about fitting in; it’s about surviving. Like in the much more recent (and underrated) Jennifer’s Body, Heathers takes the averagely gruesome reality of teenagers and nudges it to its logical conclusion. We are dreadful to each other. We imagine how much better the world would be without the tyranny of peer pressure. And so we invert and expand that dominant force explosively, depleting the universe of Heathers.

What, if anything, is wrong with that?

What, if anything, is wrong with that?

It is this question that Heathers explores. It takes the normal romances, and betrayals, and social strata of high school existence and wrings it out like a bathroom mop. There is no coy in Heathers. There is no adult propriety. These teenagers are as vulgar and ungoverned as teenagers really are.

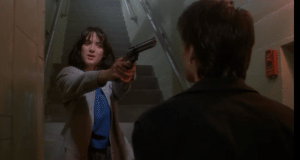

They are dangerous to themselves and others.

In short, Veronica finds herself savaged by the machine she operates. Under the seduction of the psychotic J.D., she tries to redirect the destructive force back on the system, but the system, well, it’s made of people. Each as terrified and manipulated and faulty as the next. Lop off one Heather, and there’s always another to take its place.

The best parts of the film come from Daniel Waters’ script, which is evil in its lacerating power. Dialogue and situations shred your expectations as a thresher would a field of paper dolls. Every time you expect the script to hold back, it shows no mercy. Michael Lehmann’s direction, too, offers just enough style to accentuate this substance. Neither went on to do anything else that matched Heathers’ significance. Somehow, the caustic magic these two collaborated on here got usurped — and then squandered — by Tim Burton.

In terms of the acting, these are difficult roles to make feel authentic. On one hand, Ryder and Slater communicate the drama and emotion of their age. On the other, the film forces them into an in-between world of imaginations gone astray. I do not buy them as real people in Heathers. I do appreciate what they add to the fable, though.

In terms of the acting, these are difficult roles to make feel authentic. On one hand, Ryder and Slater communicate the drama and emotion of their age. On the other, the film forces them into an in-between world of imaginations gone astray. I do not buy them as real people in Heathers. I do appreciate what they add to the fable, though.

I watch the film and remember vividly how seeing The Breakfast Club, with its cheery, hopeful ending made me feel morose. I was no archetype brain, or jock, or beauty queen and I was never going to somehow, miraculously, endear myself to my school’s Molly Ringwald or even its Ally Sheedy.

Heathers ends ugly. There’s hope, but its small and personal. You can’t change the course of teen culture. All you can do is survive — and pick your friends more carefully.

I love my dead gay son!

I need to watch this one again soon.

Yes. You do. So many great lines of dialogue I’d forgotten.

and now there’s this: http://heathersthemusical.com/

Perhaps there’ll be a whole musical number called “I Love My Dead Gay Son!” With tap dancing, of course.

Winona is still rambling about a sequel, but it’ll never happen.