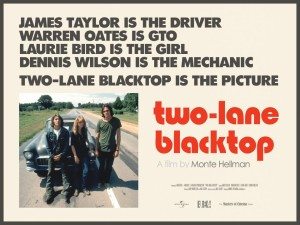

Two-Lane Blacktop (’71) is a movie without a beginning or an ending. It’s all middle. The adventures of two guys making money racing their matte grey, souped-up ’55 Chevrolet 150 in which the races—maybe three total?—are barely seen, shot to imply their meaninglessness to what’s really happening.

Nothing is really happening. And nothing is everything. Unless it isn’t. Unless it’s really, actually nothing. Which might be a terribly important thing to realize. Unless it isn’t.

The two young men in the car are identified as The Driver and The Mechanic (musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, respectively). All they ever talk about is the car when they talk, which is rarely. They are two serious young men. The Mechanic is cool and unflustered. The Driver shows a bit of intensity, anger, even, at times. These times are infrequent. He seems to enjoy giving people shit about their shitty cars and bragging about his own. He loses no races until the final race, but we don’t see how that one ends (unless we do), so he might win that one too, unless he doesn’t. Or unless losing is winning. Or the other way around.

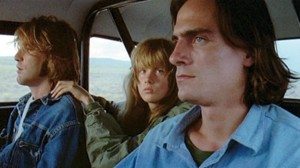

They pick up a girl and take her with them. Only they don’t actually pick her up. They’re eating at a diner, not saying a word. Out the window behind them we see a Volkswagon bus pull up. A girl gets out, The Girl, in fact (played by Laurie Bird), with a beat-up duffel bag and a white fluffy handbag. She walks to the Chevy and gets in the backseat. When The Driver and The Mechanic get in, they don’t so much as look at her, let alone speak. Off they go.

Are they headed anywhere in particular? They don’t say. They need money and they make money by winning races. They drive to small towns, find out who’s got the hot car, and challenge them to a race. But again, this happens maybe twice turing the movie, and the races are barely shown.

What is shown is the movie’s other character, GTO (Warren Oates), who drives a show-offy, bright yellow ’70 Pontiac GTO, but knows nothing about cars. He’s the only character we learn anything about, but since everything he says about his life history is a lie, we don’t know a thing about him, aside from the most important thing: what kind of a man he is. What kind is he? For starters, he’s lost, and going nowhere.

He picks up hitchhikers for the purpose of having someone to tell his life history to, which history is completely different every time. One such hitchhiker is played by Harry Dean Stanton as laid-back gay cowboy who makes a pass at GTO. He isn’t interested. He’s interested in himself. And his car. And driving it.

There is sex in the movie. The Mechanic gets it on with The Girl, and later she gets it on with The Driver. After which The Driver seems to become attached to her. But by this time she’s riding with GTO. Everyone wants to take The Girl someplace. New York, Florida, Ohio. She likes the sound of some places but not others. Or so she says. What she likes most of all is going somewhere. Being there, wherever there happens to be, is not her thing.

GTO imagines he’s being followed and therefore in some inscrutable way harassed by the Chevy. When both cars show up at the same gas station he confronts The Driver. First he plays with a bottle of Coke. Drinks from it. Puts it aside. Picks it back up, drinks, puts it away again. Oates gives by far the best performance in the movie. He’s perfectly insecure and cocky.

Which is not to say Wilson and Taylor and Bird aren’t excellent too. It’s that what they’re doing is not what you’d call a performance, at least not in the usual sense. They are, as their names suggest, archetypes. Of what, it is not entirely clear. Nor is it supposed to be. They are representations of people. These actors, or non-actors, function perfectly in their roles.

The Driver, never one to back down, calls out GTO for being crazy, with regards the notion he’s being followed. He and The Mechanic challenge GTO to a race, and not a drag race, a race to Washington D.C., and not for money, “for pinks,” i.e. pink slips, both of which they put in an envelope and mail to D.C.

The race is on.

But it’s not a race. Or not yet. Or it is. Or it never is. The Mechanic sees trouble brewing with GTO’s engine, but he and The Driver don’t want to find themselves far ahead. What’s the point in that? They switch cars, and drive to the next town, there to wait in the rain for anyone to show up at the deserted gas station. Most places in the movie are deserted, or close to it.

Monte Hellman directed Two-Lane Blacktop from a story by Will Corry and a script by Rudolph Wurlitzer, something of a cool underground writer, author of surreal little books like Nog, and whose unproduced acid-western script Zebulon would almost be made by any number of big deal ‘70s filmmakers before eventually inspiring Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. He also wrote the script for the ‘80s Alex Cox movie Walker, which movie killed Cox’s Hollywood career, and is awesome.

The dialogue in Two-Lane Blacktop is odd but not in the abstract sense. It’s odd in its brevity and lack of information. The direction and editing is odd but not in a way that calls attention to itself. It’s odd in what is shown and what isn’t shown. Which is to say, you don’t so much notice anything odd about it until you think about what you saw after it ends. It’s shot in widescreen, often under cloudy skies. Its colors are muted. You feel the Chevy’s speed when it tears past in wideshots and when you’re in the backseat looking out the front window.

Two-Lane Blacktop is something of a cult film, though it garnered plenty of attention when it came out. Critics liked it. Audiences didn’t quite know what to make of it. Actually critics didn’t either, they just recognized that something with great purpose was on screen and that it demanded attention. Or so they said. It was the kind of movie much written about and little seen.

It’s not a boring movie, despite nothing happening. No one ever makes it to D.C. The Girl takes off with a boy on a motorcycle. GTO is last seen driving east, hoping to win, telling his latest hitch-hiker that he won his Pontiac in a race for pinks. The Mechanic is last seen prepping the Chevy for another small-town race. The Driver is last seen driving, racing against a black El Camino. We don’t actually see the El Camino racing. We’re in the Chevy with The Driver, the car rattling with speed, the open road ahead. That’s when the film melts and there’s no more movie.

Which means what? Does he lose? Does he win? Does he die? Does it matter? I don’t know. I don’t mind not knowing. Whatever Two-Lane Blacktop is, I like it.