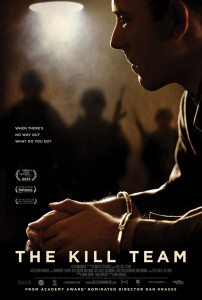

Dan Krauss’ new documentary The Kill Team leaps directly into the shit. As you may be aware, American soldiers were convicted of murdering innocent Afghani civilians during their tour overseas. This film explores that story, but there are two stories. One is about the fact that soldiers, trained and encouraged to kill, found a way to do exactly that regardless of circumstances.

Dan Krauss’ new documentary The Kill Team leaps directly into the shit. As you may be aware, American soldiers were convicted of murdering innocent Afghani civilians during their tour overseas. This film explores that story, but there are two stories. One is about the fact that soldiers, trained and encouraged to kill, found a way to do exactly that regardless of circumstances.

That’s a potent story about something universally important to humankind.

The other story is about Specialist Adam Winfield, who attempted to alert the military to his unit’s criminal behavior and found himself embroiled in the same. This second story forms the backbone of The Kill Team and that’s a shame. Adam Winfield’s moral dilemmas are of interest, as are both his course of action and the results. They are not nearly as interesting as what makes soldiers soldiers and what makes killing murder.

The Kill Team, with impressive access to Winfield and his family, walks the viewer through how this particular group of soldiers planted weapons near Afghani men and boys. Then the soldiers killed those men and boys because they wanted to. Interviews with Corporal Jeremy Morlock and PFC Andrew Holmes — willing participants in these murders — will nauseate you. To them, their victims weren’t people. Even now, after being convicted of war crimes, they grin at the violence they unleashed. That’s what soldiers are when they’re being soldiers, they shrug and say.

Winfield, whose struggle underpins the film, felt differently and may have acted differently.

Finding himself amidst men without honor — as he describes it, everyone serving in Afghanistan — he reaches out to his parents for guidance. He attempts to report these atrocities through them. But with his life threatened by the Kill Team’s ringleader, Staff Sargent Calvin Gibbs, Winfield keeps his mouth shut. He participates in the killings to some degree.

Then, finally escaping the hell of war, he returns home to find himself charged with the crimes he failed to stop.

It is hard not to compare this documentary — about the violence we commit and our awareness of its effect — to last year’s The Act of Killing. Both films focus on a single person, walking us alongside them as they encounter and become involved in murder. In The Act of Killing, the filmmakers achieve something monumental; they capture a killer’s expanding awareness of his crimes. In The Kill Team, Adam Winfield undergoes no growth of understanding. He and his parents anguish over the choices they made, but the film does not press them to confront their complicity. They do not judge themselves.

Winfield does not report the crimes of the Kill Team because he is afraid. Then another soldier, PFC Jason Stoner, joins the unit, doesn’t appreciate the guys smoking hash in his room, and reports them. For his snitching, he is beaten. So he snitches again and the whole ugly truth comes out. Not even really intending to put a halt to murder, Stoner does so. Because he isn’t afraid.

Stopping the crime is accidental and easy. The only scars Stoner must live with are those of being labelled a whistle-blower. He just didn’t like his room smelling like hash and so people remain alive.

A documentary isn’t, shouldn’t be, fiction. The story is what the story is. The Kill Team simply skirts a fantastic story in favor of a banal one. Krauss’s film sets Winfield up as a man trapped by impossible circumstances, but those circumstances are not impossible. All the while, there behind him, within him, is the cold flint of war scraping relentlessly for a spark.

Well here is that spark. There is that boy’s body. Around us stand the men who killed him. What questions do you want to ask these people? Perhaps you’re curious as to the scope of this problem, which The Kill Team alludes to. Maybe you’d like to know what a representative of the military has to say, or even an objective third-party? I’d like to ask Adam Winfield if he thinks he deserves to be convicted.

The Kill Team reveals a ghastly but unsurprising story. I would hope that the awareness it fosters instigates growth and change, but I wouldn’t count on it. War lives in soldiers and we keep building soldiers.