Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of the more colorful directors in movie history. To put it mildly. To put it another way, he was a madman. During a career cut short at age 37 by a drug overdose, he made 39 feature films in fourteen years. He was like the anti-Kubrick, who made thirteen movies in 46 years. The drugs, of which he used many, he did not use to relax. He used them as fuel. One feels inclined to bring up stars burning twice as bright lasting half as long when discussing him. The man left an impression.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is one of the more colorful directors in movie history. To put it mildly. To put it another way, he was a madman. During a career cut short at age 37 by a drug overdose, he made 39 feature films in fourteen years. He was like the anti-Kubrick, who made thirteen movies in 46 years. The drugs, of which he used many, he did not use to relax. He used them as fuel. One feels inclined to bring up stars burning twice as bright lasting half as long when discussing him. The man left an impression.

Fassbinder’s ouvre is not one I’ve delved into deeply, having seen but a handful of his movies over the years, most memorably his extremely odd and long science fiction movie, World On A Wire (Welt am Draht, ‘73), a movie I’m glad I saw, though one I’m not sure whether or not I liked, exactly. Others I remember less well, but I’m beginning to think I need to revisit some of them, like Chinese Roulette (’76) and The Marriage of Maria Braun (’78), and to delve into the many I’ve never seen, like Veronika Voss (’82) and The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant (’72).

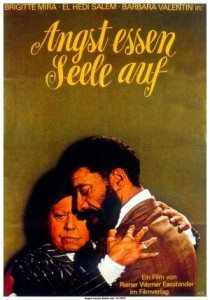

Why? Because I recently watched Ali: Fear Eats The Soul (Angst Essen Seele Auf, ’74). It’s a kind of updating or remaking or reimagining of Douglas Sirk’s melodramatic masterpiece, All That Heaven Allows, and it’s fantastic. Fassbinder, after his early period making highly theatrical films, found his first international fame with Fear Eats The Soul, a movie dealing explicitly with class and racism and romance and loneliness and, as in all his movies, the rotten core of German society, though in the case of Fear Eats The Soul, the attitudes and opinions of the characters would fit neatly into any society.

Fassbinder takes the basic set-up of All That Heaven Allows—an older woman falls in love with a younger man belonging to a class her friends and relatives disapprove of—but he in no way imitates Sirk’s style of extreme melodrama. Fear Eats The Soul is a movie stripped to its basics. It is austere and straightforward and all the more powerful for it.

Fassbinder uses theatrical tableaux throughout, perhaps most strikingly in the opening shot of a bar into which Emmi (Brigitte Mira), an older German woman, enters seeking shelter from the rain. Within are a number of foreigners, including a Moroccan, Ali (Al Hedi ben Salem), all of whom stare at this unwelcome intruder. Like Sirk, Fassbinder frames characters within doorways, against windows, between the handrail posts of wide winding stairways. Everyone in the movie is in one way or another trapped.

In one visually intense scene, Ali and Emmi meet at an outdoor café on a rainy day. They are alone, seated at a yellow table among a sea of yellow tables and chairs. In the background, in a frozen tableau, the emloyees stare at them, full of hate.

Why the hate? Because Ali is a foreigner. Thus making Emmi, in the words of everyone, including her three grown children, a whore. Fassbinder himself plays Emmi’s son-in-law, an angry, mean, racist bastard. When Emmi invites her children to her home to meet Ali, whom she’s just married, they are outraged. One of her sons kicks in her TV set, another nod to Sirk’s movie, in which a television plays a major part.

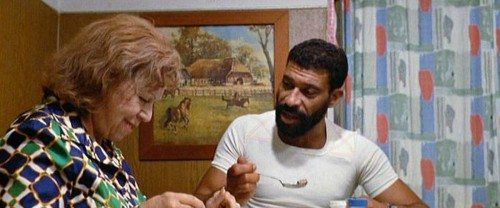

I love how quickly and simply the story progresses. Ali asks Emmi to dance at the behest of the bar owner, Barbara (Barbara Valentin), in the first scene. They dance. Ali volunteers to walk Emmi home. She invites him up for a drink, learns he shares a single room with five other Moroccan men, and invites him to stay in her spare bedroom. He can’t sleep, goes to her room, says he is lonely, puts a hand on her arm. Fade to black.

Ali’s German is the stilted German of a foreigner. The title comes from one of his lines, quoting an Arab proverb: Angst essen Seele auf, which literally translates as “Fear eats soul up.” The English subtitles are likewise broken, to reflect Ali’s speech.

It’s not long before they marry. Everyone in Emmi’s life shuns her. Her neighbors in her apartment building harass her. Her coworkers, women she cleans buildings with, refuse even to speak to her. The grocer won’t sell anything to Ali and when Emmi complains refuses to sell to her. And of course her children walk out on her. She holds up as long as she can, because why should she feel shame? She’s in love. But she can’t take being hated forever. Ali says he’s used to it, but he’s internalizing the pain. Is it enough for them to have only each other? Often when they’re together, Fassbinder shoots them from a distance, surrounding them with empty space. No one will come near them.

Later in the film, the hatred suddenly thaws. Emmi is befriended anew. Why? The grocer wants his best customer back. The neighbor ladies need Ali’s help moving furniture. The coworkers want to team up to demand a raise, and anyway a new Yugoslavian woman has been hired. They treat her as they did Emmi, and Emmi acts no better. Reaccepted by her community, albeit for wholly selfish reasons, Emmi begins to treat Ali like a kind of prize pet to be shown off. It doesn’t sit well with Ali, who spends nights away, whose coworkers mock her. Will it be the end of them?

Fassbinder gets incredible performances out of his actors. Brigitte Mira as Emmi is one of those actors who with the smallest change in expression communicates layers of conflicting emotions. Salem seems barely to do anything you’d call “acting.” He moves little. Has few expressions. But man is he ever present.

This might have something to do with his in fact being an immigrant, and in fact having left a wife and children behind in Morroco, same as Ali. Furthermore, Salem was Fassbinder’s boyfriend for a few years. Fassbinder openly identified as gay, though maintained relationships throughout his life with both women and men. Salem and Fassbinder’s breakup did not sit well with Salem, who eventually stabbed three men in a barfight, fled to France for a couple of years, and eventually killed himself in prison. One supposes he was a man of passions. Like Fassbinder.

The other actors are fine too. All of them have incredible faces. They look nothing like movie stars. They look used up and tired. Their souls eaten by fear?

Ali: Fear Eats The Soul is not a normal movie. It’s both highly artificial and simply naturalistic. Fassbinder shot many scenes in one take. He wrote one draft of the script and shot it as is. The movie was edited in only four weeks. You can sense the hurried nature of the production, yet what’s onscreen is a beautiful, carefully crafted work of unusual power.

okay fine. i’m watching this with All That Heaven Allows as a double feature, having not seen either. which should I do first? the Sirk?

Yes, Sirk first. And if for some insane reason you aren’t greatly entertained by that one, don’t worry. Ali, though a retelling, is a very different kind of movie.

I liked the Sirk better. Although I liked the Fassbinder, too. Such deeply layered shots.