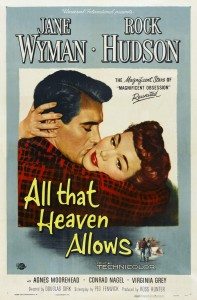

When director Douglas Sirk was making his melodramatic movies in the ‘50s, critics loathed them, and audiences ate them up. They were perceived as romantic, overwrought, simplistic junk for housewives, “women’s movies,” they were called, an actual genre at the time (today we’re cool and ironic and call them “chick flicks”). They starred people like Rock Hudson and nobody took them seriously.

When director Douglas Sirk was making his melodramatic movies in the ‘50s, critics loathed them, and audiences ate them up. They were perceived as romantic, overwrought, simplistic junk for housewives, “women’s movies,” they were called, an actual genre at the time (today we’re cool and ironic and call them “chick flicks”). They starred people like Rock Hudson and nobody took them seriously.

Fortunately, in the years since, it’s dawned on many that Sirk’s films are anything but simplistic and treacly. What are they? They’re savage deconstructions of social, sexual, and societial norms in the form of outlandish, melodramatic, tragic love stories, filmed with an artful, knowing precision to the point they feel like carefully choreographed dance.

I was floored by Written On The Wind when I saw it a couple of years ago. How could anyone have missed its subversive nature? It’s one of the most outrageous movies I’d ever seen! Yet they did and they do. Last night I watched All That Heaven Allows (’55), and I can’t remember the last movie I enjoyed so much. Every scene—every line—leaves you with your mouth hanging open. How can they get away with that?! This is insane! I said in reference to literally everything that happens.

All That Heaven Allows plays like the kind of ironic, scathing take-down of a past era you’d assume was made twenty years after the fact. That it’s made in ’55 seems impossible. How did a social critique so blinding pass by as if invisible?

Was it because people at the time were living in the society being critiqued, and couldn’t step outside of it to see its inherent absurdity? Maybe. But then again, what it showed, according to detractors, was a simplified Hollywood version of reality. So maybe the fact that it was Hollywoodized precluded anyone looking deeper? I think this makes some kind of sense. Viewers at the time must have seen Sirk’s characters for what they are on the surface: outrageous stereotypes, each with a simple, starkly lit character trait, each serving a blatantly melodramatic purpose. But with just a little perspective, it’s easy to see that his simple stereotypes are designed to highlight the absurd.

Here’s the story in a nutshell. A well-to-do widow, Carly (Jane Wyman), with two grown children, a daughter in college and a son just out, living in a very nice middle-class ‘50s house and neighborhood, is a bit sad, a bit at loose ends. An older, well-off businessman asks for her hand in marriage, not out of passion, but to comfort each other as they age. And at a fancy party, a married man drunkenly propositions her. She’s interested in neither offer.

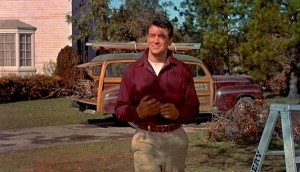

Then she meets her gardener, Ron (Rock Hudson). He’s a confident, free-living man, about to embark on a career as a tree-farmer (!), whose friends are inspired by him to read Walden, not because Ron’s read it, but because he embodies it. He lives in a restored barn in the woods. He and Carly fall madly in love. He asks her to marry him. But Carly’s society won’t accept him. Her children won’t accept him. What will she do? Let down everyone she knows? Or deny herself true love?

If reading that you threw up in your mouth a little, I don’t blame you. And you haven’t even seen the colors. Sirk loves Technicolor, which I’m beginning to suspect was invented expressly for his use. The opening shot, of a town square in the fall, is like a Norman Rockwell painting of a Norman Rockwell painting.

But the colors aren’t garish, exactly. Or not always. Or at any rate never without reason. Sirk is a master of light and shadow too. Interiors glow. A single room might be divided by color and light into three separate zones through which the characters move. Romantic moments you’d expect to be brightly lit take place in the shadows.

Carly’s daughter, an overly intellectual college girl, brings up the ancient Egyptian practice of wives being walled up in the tombs of their deceased husbands. Over the course of the movie, Sirk uses colors and framing to do the same to Carly, boxing her up in windows, mirrors, doorframes, scene after scene. When a TV shows up in her house at the end, she’s literally trapped within it, there to watch the rest of life pass her by outside.

Ron’s friends are all a bunch of wine-swilling bohemians–artists and foreigners and weird old guys and so on. They’re as absurd as Carly’s socialites. Everyone in the movie is trapped not primarily by their chosen social milieux, but by their conceptions of themselves, Ron as much as Carly.

What kind of movie is this? There’s a scene where Ron, outside his house/barn, feeds a friendly deer. Which maybe you have to see to fully appreciate.

I can’t recommend All That Heaven Allows too highly. Or for that matter, Written On The Wind. Douglas Sirk knew exactly what he was doing, even if nobody else in the ‘50s did.

I have watched this film and it pleased me greatly.

I am sorry that I smashed your teapot, if you know what I mean.

The teapot? How could you! You fiend!

Pingback: #125 All That Heaven Allows – 1000 Films Blog·