Ever since The Sopranos cut to black, creator David Chase has been hounded by fans and reporters and random people on the street and even actual hounds, all demanding he tell them whether the abrupt ending implied Tony’s death or continued existence. Chase’s answers over the years have differed in wording, but all boil down to the same thing: you’re asking the wrong question.

Hounded to the point of exhaustion by a reporter at Vox recently, Chase seemed to give, finally, a definitive aswer: Tony’s alive. The accompanying article is reasonably interesting, but having asked the wrong question, its thrust is to argue that, even, now, knowing the answer, it doesn’t matter, what’s interesting is the ambiguity, and how it ties into the rest of the series and to Chase’s life and influences and beliefs.

The next day, Chase’s publicist wrote in to explain that in fact Chase had not given a definitive answer, that whether Tony lives or dies is a spiritual question with no right or wrong interpretation.

To which Vox argues is what their original article was all about. Chase, they write, is offering a non-denial denial. He answered the question in a moment of weakness, but is now, once again, saying the answer isn’t the point.

The problem with both articles at Vox is the part where they believe an answer has been given. All their highminded talk of the destabilization of endings and the art of closure and how knowing is no better than not knowing and on and on is rendered moot by their belief that a nonexistent question has been answered. In other words, it’s only because they’ve been given an answer (or so they believe) that they’re able to let out a sigh of relief and write a piece about an answer not being the point. It’s like a rich man explaining that what’s important in life isn’t money.

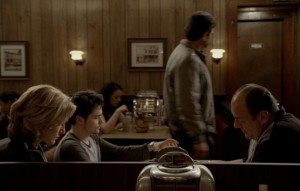

Is Tony alive at the end of The Sopranos? Certainly he is. Look at him there, savoring his onion rings. Alive. Cut to black. Does his life go on after the cut to black? Yes—but. He’s going to die sooner or later. Does he die in the very moment of cutting to black? Maybe. Maybe he dies five minutes later. Maybe he dies ten years later.

Wearied by a reporter hellbent on “solving the mystery,” (so she could then write an article on the power of endings with nontraditional resolutions), did Chase reveal the “truth”?

No. Because even if he did, he didn’t. The show is the show. The show is not what David Chase says the show is. The show tells us what it tells us. What it tells us is that asking whether or not Tony lives or dies is not what to ask. The show doesn’t ask it, why should we? What we should be asking is this:

If the ending isn’t about Tony living or dying, what is it about?

To that question there’s no one answer. This is what Chase means when he says it’s a spiritual matter. The ending is meant to evoke an emotional response, and that it does. When I recently re-watched the entire series I watched it with someone who’d never seen the show before. I told her to prepare for an unusual finale, but said no more. When the show cut to black, and once she’d had a few seconds to realize it was over, she threw a pillow at the screen and stormed out of the room. This normally calm, low-key TV viewer. She was enraged. For days. Not because she’d been “cheated” in any way. “Enraged” is the wrong word. She was affected. Deeply.

That’s how you end a show. Has any show done it better? Nope.

The Sopranos is not a soap opera. It’s a character study. It’s about Tony Soprano. Everything that happens on the show ties into Tony. Timewise, episodes don’t follow one immediately one after the other. Sometimes days have passed, sometimes months. Seasons have story arcs, but those arcs, whatever else is going on with whichever characters, are only about one thing: Tony. The show is cumulative. We go deeper and deeper into the psyche of one man as it progresses.

Tony is obsessed by mortality. What is life? What is death? How to live? How to die? This is what he faces in every show, sometimes head-on, sometimes obliquely. Death surrounds him. But he is alive. What to do with his brief time?

He never answers that question. He only asks it. Again and again he asks it. He absolves himself of any wrongdoing by going to therapy, but therapy doesn’t change him. It’s his form of confession. His existence at the end of the show follows the same pattern as it does at the beginning.

When the ending first aired, I was convinced he’d died. Clues abounded. The man in the Member’s Only jacket; Tony wearing the shirt he’d worn when shot; the painting of the orange cat; the strange angle of Tony looking at himself through the window of the restaurant; his discussion with Bobby about not feeling the bullet that kills you; the shot of Tony waking up in bed as though lying in a coffin; the very structure of the final scene, ramping up the suspense as though a hit is imminent; the fact that the entire show is shown through Tony’s perspective, so that should he die, what could happen but a cut to black?

But watching it again, thinking about it further, I saw that every one of those elements fits his not dying just as well. From Tony’s perspective, that’s his life, the very real possibility that he will be shot dead at any second. Every person suspicious. Every action full of portent. Every detail of his life a potential sign, an omen of death. An endless feeling of building tension, only to be released when–When?

Does he die? Does he live? Both and neither. He goes on and on and on and–And then he doesn’t.

We want stories to have endings. And we want our endings to tell us what everything that came before means. This is arguably the fundamental purpose of stories, to make sense of life in a way life refuses us. When artists toy with closure, it can be upsetting, even if, as with The Sopranos, we’re given a closure with unusual weight and power, one we’re discussing years after the fact.

Chase was influenced by Twin Peaks, in which, like The Sopranos, dreams, dream states, and alternate ways of “knowing” are key to the story. In interviews Lynch never offers explanations of his work. He’ll talk at length about his ideas and his methods, but interpretations he leaves to the viewer. Chase has done the same. Did he reveal something to the reporter at Vox? Again, even if he did, he didn’t. The end of The Sopranos isn’t designed to be “solved.” It’s designed to be felt in the same way a dream is felt. There is meaning in a dream, but not in the form of words and logic. There is no “answer” to be found at the end of The Sopranos because the question obsessing viewers—does Tony live on or die when the screen goes dark?—isn’t asked.