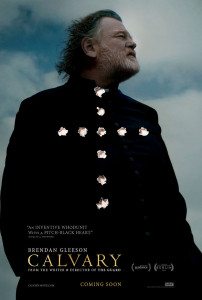

John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary — Brendan Gleeson playing a priest who’s been informed he’ll be murdered in a week — is the sort of film that sparked my neurons during dream state. To my mind, awake or asleep, that means it earns the benefit of the theological doubt.

John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary — Brendan Gleeson playing a priest who’s been informed he’ll be murdered in a week — is the sort of film that sparked my neurons during dream state. To my mind, awake or asleep, that means it earns the benefit of the theological doubt.

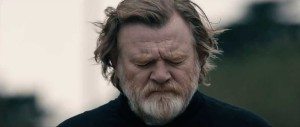

While the movie was actually screening, I mostly just appreciated Gleeson’s lead performance: the kind of work you could hang anvils from without any noticeable loss of integrity. He’s a rock. He’s comic. He’s devastated. He’s soused and he’s quietly furious and also very disappointed in you, because he loves you.

In Calvary (so named after the Jerusalem-adjacent location of Jesus’ crucifixion) Gleeson’s Father James Lavelle hears your confession. Unfortunately, what you’re confessing is a desire to kill him, because he holds no blame.

At the film’s start, an unseen man tells Father James, confesses to him, that he was serially and horrifically abused by a priest as a boy. Because the offending priest is dead, and because no one will notice a guilty priest being killed, this man will kill James. He gives the Father a week to get his house in order.

Like McDonagh’s previous film, The Guard, this one is darkly comic — although I rarely found it funny and certainly never laughed. It is rife with recognizable faces, each playing a different quirky resident of this small Irish village, which is seemingly only populated with film characters. There is the quarrelsome husband (Chris O’Dowd), a nympho wife (Orla O’Rourke), a humorless immigrant (Isaach de Bankolé, frequently cast by Jim Jarmusch), a wealthy prick (Dylan Moran), a reclusive writer (M. Emmet Walsh), and so on.

Like McDonagh’s previous film, The Guard, this one is darkly comic — although I rarely found it funny and certainly never laughed. It is rife with recognizable faces, each playing a different quirky resident of this small Irish village, which is seemingly only populated with film characters. There is the quarrelsome husband (Chris O’Dowd), a nympho wife (Orla O’Rourke), a humorless immigrant (Isaach de Bankolé, frequently cast by Jim Jarmusch), a wealthy prick (Dylan Moran), a reclusive writer (M. Emmet Walsh), and so on.

James wanders among his flock, knowing what we don’t, that being which of these mugs intends to kill him on Sunday.

In that way it is just like Snowpiercer, but with fewer trains. Meaning we are not watching the story of real people in a real world, but rather seeing symbolic figures acting out a parable. In this case one about what it means to die for someone else’s sins. What it means to embody forgiveness.

In that way it is just like Snowpiercer, but with fewer trains. Meaning we are not watching the story of real people in a real world, but rather seeing symbolic figures acting out a parable. In this case one about what it means to die for someone else’s sins. What it means to embody forgiveness.

Hysterical, right?

As I said, I wasn’t enraptured by Calvary. It’s got moments of ripe beauty — landscapes, the sea, Gleeson’s beard whipped by the wind — and dialogue to chew on. Many of the supporting characters are as irritating as possible, particularly Aiden Gillen’s Dr. Frank Harte (Gillen being Littlefinger on Game of Thrones and Mayor Carcetti from The Wire), and I assume that was intentional. These are people for whom one would feel challenged to die.

I suppose Jesus might have felt the same way about us, and our ancestors.

I suppose Jesus might have felt the same way about us, and our ancestors.

And that’s interesting to consider, theologically and intellectually. We talk about the so-called son of god dying for our sins, and about how much he loves us all, even today, but we don’t pause to consider how vastly unlovable we all are. Or how it helps anyone — if it does — to suffer for others’ mistakes of morality.

To Calvary‘s credit, I believed Father James Lavelle to be the sort of man who might actually keep an appointment with a fellow who intends to murder him. The fact that McDonagh couched James’ gradual journey towards death in dark comedy lessened the parable’s impact, but so it goes.

I didn’t think much of Calvary when I watched it, but that evening, in my dreams, I explained it all to someone and convinced them of its universal importance.

I’d love to do the same for you, but I’m awake now. I remember Brendan Gleeson’s performance. I remember the way the surfers floated out to sea. I remember a conflagration, urine, an unlikely serial killer, and moments and emotions but I struggle for clarity of meaning. I cannot recount the sermon.

Calvary asks us a question, then, but gives us no answer. If we believe Jesus died for our sins — willingly, of his own accord — what does that say about our guilt and our purpose? Is foregone forgiveness anything more than permission to perpetuate the causes of pain? Or is it balm for the anguish that will always exist, regardless of what our wishes and prayers result in?

Calvary asks us a question, then, but gives us no answer. If we believe Jesus died for our sins — willingly, of his own accord — what does that say about our guilt and our purpose? Is foregone forgiveness anything more than permission to perpetuate the causes of pain? Or is it balm for the anguish that will always exist, regardless of what our wishes and prayers result in?

Either the messiah will come or he won’t. And that’s the Catch-22 Calvary lays claim to. For if he’s coming, and we forgive each other anything, when could we possibly be ready? And if he isn’t, and we handle the world accordingly, maybe he might just show up to see how we’ve fixed up the place.

It does not serve the world for Father James Lavelle to announce one man’s suffering with the finality of his own. Watching this occur is not funny, even darkly. But it does apply a sacrilegious shock to the system.

The fact that I react to this shock, even well after Calvary left my presence then, means McDonagh did something right. He poked my conscience with a stick, to see if it was still living.

I’m glad to say it remains as twitchy as ever.

Oh man I loved this film. Maybe I watch too many Tom Cruise shoot-em-ups, but I thought this was the best movie I had seen in a long time. It was like a play where not a single line is wasted and every character is critical to the plot. Rife with symbolism, did the flock of sinning townsfolk represent the 7 sins? Maybe the 10 commandments?

Most fascinating was the priest himself. He had a daughter, a red convertible, a history with alcoholism and was more of a shrink than a priest, as one review pointed out. And yeah it was hardly a comedy, it was a who-dunnit drama.

I too spent a few days thinking about the movie after I had watched it. And who killed Bruno the dog?

Yeah it was more of a play, I never thought about that but it is more like a play.

The dog is killed by the same guy, it’s pretty clear he is lying when he says it wasn’t him.

I’m not sure Mash. I think the dog dying is another comment on the state of the world; perhaps misdirection but more like the irrationality of suffering. Someone just killed his dog because people are inexplicable and in pain.

Although I suppose it could have been the same guy.

It rode an interesting line between overtly symbolic and human, not always successfully in my mind. Some of the scenes/characters were a bit too extreme; i.e. the serial killer who just happened to live in this wee town.

But it raises massive theological questions with a tough perspective it’s hard to brush off. I liked it. And Gleason is great.

I enjoyed this a lot. But Aidan Gillen consistently took me out of the movie. He seemed to still be playing Littlefinger.

The ending really got me ‘Did you cry?’ that made me think and it made me feel bad.

Yep. I liked him as Carcetti in The Wire and haven’t much cared for him since.

It’s been a while since this film has been in my head. The ending scene you speak of was great; but then the coda… like the humor, it just didn’t seem to fit tonally.

But I’ll keep watching McDonagh’s films. The Guard is also good.