There is no mistaking Klute (’71) for anything but a movie of the ‘70s. The shadowy cinematography (courtesy of the master, Gordon Willis), the minimal dialogue, and the story, a character study in the guise of a murder mystery. Directed by Alan J. Pakula, it’s the first movie in his (and Willis’s) paranoia trilogy, followed by The Parallax View (’74) and All The President’s Men (’76), and while I like those two better, Klute, which I’d avoided seeing until recently, is very good. As much as it reminded me of The Parallax View (when I started it I thought, “Pakula, right, now what did he direct?” and within minutes knew he’d made The Parallax View), it’s equally reminiscent of Coppola’s The Conversation, the other most paranoid movie of the ‘70s.

There is no mistaking Klute (’71) for anything but a movie of the ‘70s. The shadowy cinematography (courtesy of the master, Gordon Willis), the minimal dialogue, and the story, a character study in the guise of a murder mystery. Directed by Alan J. Pakula, it’s the first movie in his (and Willis’s) paranoia trilogy, followed by The Parallax View (’74) and All The President’s Men (’76), and while I like those two better, Klute, which I’d avoided seeing until recently, is very good. As much as it reminded me of The Parallax View (when I started it I thought, “Pakula, right, now what did he direct?” and within minutes knew he’d made The Parallax View), it’s equally reminiscent of Coppola’s The Conversation, the other most paranoid movie of the ‘70s.

The character being studied is call girl Brie Daniels (Jane Fonda, who won her first Oscar for the performance). Seems a man has gone missing, one of her johns from two years prior. The man’s wife talks with police in the presense of her lawyer, Peter Cable (Charlies Cioffi) and a private detective, John Klute (Donald Sutherland). After six months, they’ve found nothing. They talked to Brie, but learned nothing. She didn’t remember the guy. The lawyer says Klute will be taking over.

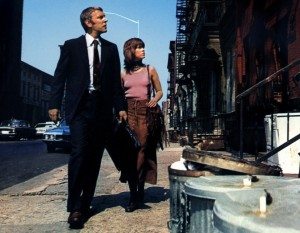

Sutherland is as reserved as I’ve ever seen him as Klute. Emotionless, affectless, soft-spoken. Fonda is wired as Brie, who’s hard on the outside and scared on the inside. When discussing her life with a therapist, she explains her attraction to being a prostitute: it allows her total control. When she’s with a client, she’s in charge, she makes the rules, she’s confident.

We soon find Klute living in a basement room under Brie’s apartment building, taping her calls. In classic ‘70s fashion, no explanatory scenes lead up to this. We know nothing about Klute. He says nothing about himself. He turns up at Brie’s door and wants to ask her questions. She eventually lets him. He hears someone on her roof. He gives chases. Finds no one.

Is someone watching Brie? Did someone kill the missing man? She and Klute follow a lead, first to Brie’s ex-boyfriend/pimp, played by Roy Scheider (channeling the future Al Pacino as Tony Montana, I swear they look like twins), then to a drug addict whore.

None of which is really the point. The point is the relationship growing between Brie and Klute. She seduces him, but it takes numerous efforts. At first it’s only for control, for her to own the situation, but slowly, she softens, and he does too.

The camerawork is deep with shadows and abstract compositions. One striking shot shows the lawyer, Cable, at his desk chair, windows behind him, pure grey sky filling them, his black desk at the bottom of the frame. He appears to be floating in space. He’s listening to one of Klute’s tapes of Brie. He’s awfully interested in them.

The revelation of who’s responsible for the missing man, and for who’s now killed the junkie whore, and for who’s after Brie, is almost elided. You realize what’s happening without being told. How can one not love ‘70s movies? Nothing like this could or would be made today. By today’s standards, Klute would play as an abstract art film. In ’71 it was a mainstream Oscar winner.

The scene between Brie and the killer at the end has him, in classic evildoer style, telling her how and why he did what he did, just enough time for Klute to arrive and save the day. Is the killer thrown out a window? Does he jump out? What happens in the final scene? It’s unclear. It doesn’t matter. It’s over. Do Klute and Brie become a happy couple? What do you think?

Klute is the most personal entry in Pakula’s paranoia trilogy. It’s about one woman and the threat posed to her, specifically by one man, although the larger theme is how she as a woman is forced to deal with all of the men in her life, and how through Klute she learns to feel, to allow herself real emotions she’d previously kept at bay.

The Parallax View likewise focuses on a single character, Joe Frady (Warren Beatty), but what menaces him is either a mysterious corporation or the U.S. government, which may be one and the same. It’s a far more oblique story than Klute. In Parallax, essentially nothing is stated outright. The movie unfolds, and you’re as lost as Frady, you’re more lost. Events become eerier. Everything is shadow, shots are in close-up or from far, far away. It is a movie filled with emptiness. At the end, it’s impossible to say what has happened or what it means or what you ought to believe. Which is its point. There are forces at work you will never understand. You will never be allowed to.

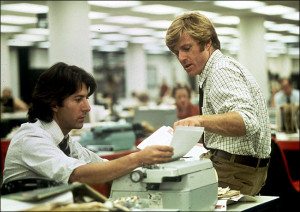

All The President’s Men takes the same theme and provides a very different outcome: the beginning of the Watergate scandal as national news and national tragedy. It’s the best movie ever made consisting of essentially nothing but low-lit, static scenes of people in rooms saying almost nothing to each other, for fear a single revealed truth will mean their death.

My favorite of Pakula’s paranoia trilogy is The Parallax View. Probably because it’s the weirdest, the most obscure, and the scariest. Scary in an unsettling, existential kind of way. I’m a fan of All The President’s Men too, but watching it recently I was struck by how peculiarly dependent it is on its historical moment. It was released in ’76, just two years after Nixon resigned. Everyone in the country had been inundated with Watergate news for like four years straight. Every twist and turn, every personality, every element of the story was known to everyone, and that’s what the movie plays on.

Because All The President’s Men isn’t about what went down in the Watergate scandal after it became a scandal, it’s a movie about how two reporters, refusing to give up, unearthed the scandal and finally, after laboring behind the scenes, brought it to national attention. At which point the movie ends. Their story of dogged discovery is the only aspect of Watergate that people in ’76 might not have known the details of (assuming they hadn’t read Woodward and Bernstein’s book, which basically everyone had). During the movie, every name mentioned, every incident alluded to, would have been instantly familiar to everyone watching, and full of portent.

I watched it with a 30-year-old who, like I’d guess many of a similar age, has a basic understanding of Watergate—there was a break-in, Nixon was implicated, he had tapes of himself saying messed-up stuff, he was impeached, or did he step down voluntarily?—but Haldeman? Mitchell? Magruder? Liddy? Ehrlichman? Deep Throat? None of these names have meaning unless you’ve purposefully studied the history, because that’s what Watergate is now: history. Makes a guy feel old.

What’s surprising is how the movie actually plays as something closer to Klute and The Parallax View now than it did in ’76. So much is only alluded to in All The President’s Men. Nothing is made clear. Names are brought up without explanation. The end borders on ambiguity. I know plenty about Watergate, I’ve read the book, but that was years ago. Watching the movie, I too felt a bit at sea. Which one was Haldeman? How would the tapes relate, exactly? Who did what when now? It’s this deeply tense, paranoid thriller where nothing is explained, and nothing is resolved. The movie ends with confirmation that a conspiracy exists, and that it goes to the top.

In ’76, none of this was a mystery. All The President’s Men, compared to The Parallax View, was a popular, logical, exciting thriller with a perfectly wrapped up ending, because the real ending was real life, and it only just went down in spectacularly public fashion.

Kudos to Pakula for delving into the paranoia of the ‘70s better than anyone (or at least on a par with Coppola). With Gordon Willis as his partner in crime, they created a visual shorthand to communicate the feeling of forces beyond our control forever lurking just out of sight. It starts small in Klute, goes wide in The Parallax View, and is finally made concrete in All The President’s Men, where through the efforts of two men, a glimmer of hope is revealed: we can learn what’s happening behind the scenes, and we can beat it.

But we can only beat it on one condition: that we don’t forget our history…

I’ve only seen The Parallax View out of these three. I watched it last year, loved it. Will have to catch up on the other two now.

Both are very much worth your time. Though neither is, of course, as out there as The Parallax View.

Klute has been a favorite of mine since I first watched it in cinema, although I would not have been able to explain by then why. Donald Sutherland has been a fascinating and neck hair-raising actor as long as I can remember and whatever he delivered, he did it in such a mesmerizing way that one felt hooked. Klute was the first instance that introduced him to me and I felt puzzled, Body Snatchers made him indelible from my mind and Day of the Locust was the moment when I was convinced the guy was from outer space. I am guilty of loving slow, talkative, paranoia-nursing and conjuring 70s movies and Klute is certainly one of them as was All the President’s Men with Robards, Hoffman and Redford in great performances. But I realized that Klute is great to look at after all these years while the latter feels somewhat dated now.

Hackman movies of the 70s were intense, grabbing and you wanted to check your home for bugs and your life for strange coincidences that don’t make sense. No other time made film watching an act of trying to understand reality than the 70s. Nowadays 90 percent of flicks appear to be high-action superhero flicks, marvel Comic adaptations or remakes of once-great-movies and I might watch a few of them for entertainment sake or for being able to join in conversation on social media. Rarely I feel similarly compelled and grabbed by a recent flicks those of the 70s did. The French still sport films where actors rather talk than perform stunts and German cinema also knows some instances of storytelling. If Hollywood produces anything with a compelling story these days, you know that it will receive 10 Oscar nominations straight away … Cinema is dead, movie-making goes on

The ’70s were certainly a rare time for movie-making. A lot of cultural moments came together, one of which was the feeling that the government could no longer be trusted, that nefarious forces were working against us and out of our control, and that life was a series of events the meaning of which would remain ever elusive.

Clearly, movies have moved on since those days. Tis a shame, I love that era too. In terms of capturing that vibe a little bit, Inside Llewyn Davis comes to mind. It’s not doing the paranoia thing, but it does present an open-ended (or closed loop, perhaps) look at a character for whom nothing is neatly tied up, or for that matter explained at all.