In the very first shot of Steven Soderbergh‘s new Cinemax series The Knick, Clive Owen stares at his feet. He’s in an amber room of fire-lit fumes, lost on opium. This is 1900 and he is Dr. John Thackery, deputy chief surgeon at the Knickerbocker Hospital in Manhattan.

That first shot — like Thackery — is genius. It’s warm enough to dampen your collar, but in you lean anyway, probing its darkness. This is how an inspired physician and narcissist views the world: as beneath his lily-white feet — even when he’s on his back, riding the dragon.

Nothing an injection of medicinal cocaine couldn’t fix.

The Knick‘s pilot episode, like all the others in its first season, is written by series creators and producers Jack Amiel and Michael Begler. They call it Method and Madness and it’s easy to see why. It arrays its elements like a doctor’s tools, although some are better sterilized than others. The sharpest, the newest instrument is Thackery himself, based on real-life medical genius and addict William Stewart Halsted.

As Thackery rouses himself to surgical duties by injecting cocaine between his toes, Soderbergh drops the first of many electronic tracks by Cliff Martinez, fuzzing and thumping our hearts up to functional speed. Carriages skitter over cobblestones, past the kind of horse power that, once it conks out, you can’t ever restart. Dead mares are faint foreshadowing here. What follows in The Knick is a lot of bloody hell.

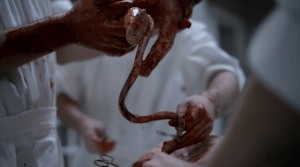

If gore isn’t the kind of thing you can stomach — or if, say, you’re pregnant — Method and Madness is not for you. At the Knickerbocker, Thackery joins chief surgeon and mentor Dr. J. M. Christiansen (none other than Max Headroom‘s Matt Frewer) in attempting a placenta praevia operation. For the uninitiated, this means they slice a woman open to save her and her baby.

And by ‘slice open’ I mean like the ox in Apocalypse Now, with results that are as likely to lead to long life for the mother as they do for the ox. This is what surgery is like in 1900. Hand-cranked suction that can barely keep up with the blood. Ether for anesthetic. The temerity to battle the will of god and win.

Following the failed procedure, Christiansen shoots himself in the head. Thackery is promoted to chief surgeon and we have our show.

Here is what is marvelous about The Knick. Amiel and Begler have lanced into a diabolically fascinating subject. How modern medicine became modern medicine couldn’t be a more enthralling or inspiring as a concept for a series. Clive Owen as William Thackery produces the sort of snide, conflicted performance he applied so powerfully in Children of Men. Soderbergh remains discontent to leave well enough alone, despite his foreswearing of cinema — this is by no means a by-the-book period drama. It is a world of mercenary ambulance drivers, crooked health inspectors, and nuns who don’t flinch when you attempt to fluster.

Thackery eulogizes Christiansen by shaking his fist at universal constants. Our life expectancy has shot from 39 a mere twenty years ago to more than 47 today! We may not be able to cheat death but we can aim our shoulders against him and shove that cretin to the wall. This, here, is where Thack throws his gauntlet in the face of god.

It is also where drama gets developed. The hospital’s wealthy administrator, Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance) takes over from her ailing father and promotes Thack to chief — despite her distaste for his egoism and sacrilege. Thack wants his colleague Dr. Everett Gallinger (Eric Johnson) as his deputy, but Cornelia insists he meet with a promising candidate from Harvard and Europe — who turns out to be black. Our scurrilous ambulance driver, Mr. Cleary (Chris Sullivan) competes for customers by wielding wooden bats in the face of any fool competition. Then he harasses Sister Harriet (Cara Seymour), who appears to serve a vicious, vindictive Old Testament almighty. A Swede succumbing to tuberculosis tells her daughter — after the girl translates her mother’s undeniable death sentence — not to be late for work at the sweatshop. The health inspector takes bribes from slumlords and the hospital’s own manager to produce and procure invalids like lumber.

It is a good day to be alive and healthy, because being alive and sick is as good as being dead. Unless Dr. John Thackery happens to be clear-headed and close at hand.

In The Knick Steven Soderbergh lets his camera scurry like a louse through the matted hair of this unhygienic system. As usual, he operates his own camera. His trademark sweep of cool and warm color creates claustrophobic interiors and alienating exteriors. There is little room for comfort, unless you’re into opium. Soderbergh also does not shy away from bloodletting, although you might wish he would.

But as much precision as there is in The Knick‘s structure, there is also a lack of grace. The black candidate who is rebuffed by Thackery — why hire a doctor who the patients won’t want to be treated by? — assists at one surgery and is so bowled by the new chief’s innovative brilliance that he refuses to go. It is clunky. Contrived. So, too, the ascendance of Cornelia at the show’s opening.

Not content with cracking the chest of modern medicine, The Knick also works in women’s rights and racial equality issues. There is nothing wrong with exploring either, it’s just the speed with which they get introduced feels televisual. More like General Hospital than M*A*S*H.

I may be picking nits, but — to be fair — The Knick has me thinking about sanitation and infestation.

I’m looking forward to seeing how the show’s bones knit. Pilot episodes are challenging; it’s hard to hit the ground running; to introduce enough characters and plot to engage without devolving into a morass of exposition. The Knick‘s launch is solid, beautiful, and potentially infectious.

We come away fascinated with Dr. John Thackery and aware of how his face looks when a young nurse injects junk into his junk. Mr. Cleary, too, stands out as a man one doesn’t know as familiar, one you wouldn’t care to know, and yet one who compels us anyway. As Chris Sullivan portrays him, the man reminds me of no one so much as Bluto from the Popeye cartoons. In the periphery, the administrators and nurses and hapless patients have room to establish themselves over time.

The Knick has already been picked up for a second season. Let us hope we survive long enough to see it play out. What with our life expectancies so expanded and our organs so engorged, our chances are mixed.