The second episode of Steven Soderbergh’s Cinemax series, The Knick, entitled “Mr. Paris Shoes”, begins to replace the unknown with information. This is not a bad thing but it’s no cause for celebration, either.

While we end up learning more about whom we’re dealing with, this doesn’t correlate to much initiation into the characters’ minds or to our investment in their goings-on. We get small, personal dramas that don’t — as of yet — add up to anything exceptional.

It’s unfair of me to ask, but compare where we are now in The Knick to the same point in Breaking Bad, or even to a less universally acclaimed show, such as Silicon Valley.

In those — and in most traditional, compelling dramas — there is a clear thing desired by a central character, something in which the audience is invited to likewise invest. I.e. To pay for cancer treatment through a combination of undervalued expertise in chemistry and overvalued desire for narcotics. Or to carry a software product across the minefield of the tech industry to a fortunate conclusion — with the fortune still attached.

In The Knick, Dr. John Thackery (Clive Owen) wants nothing so clearly relatable. He aims to advance medicine through improvement of surgical technique. This is something we know he will succeed at to some degree while also leaving work to be done. We’re still filling cancer patients like Walter White with poison and radiation after all. Thack is not working to improve medicine to save any one in particular; his goal is enormous and (so far) undefined.

He does, however, have himself to extract from the demands of opium and cocaine — again, something for which we know he will find no universal solution even if he achieves subjective success.

There are other characters in The Knick who stride towards other, similarly lofty goals. Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance) advances the cause of sexual and racial equality. In episode two, she wants the hospital her family funds to be modern. The electrical system they have spent thousands on is junk, and its malfunction leads to the death of a nurse. Hospital manager Herman Barrow (Jeremy Bobb) is to blame; his debts have led him to skim money off the contract, resulting in shoddy work. What does Herman want? He wants to keep his teeth in his mouth.

As the ensemble story fuzzes through in pulses — swapping dissociative Cliff Martinez electronic music with scenes that feel unfortunately cribbed from Downton Abbey — we also get the unsubtle story of Dr. Algernon Edwards (Andre Holland). He is the black physician whom Cornelia has forced upon Thackery as deputy. He lives in a squalor, in fact, opening the episode with his eyes, a cockroach, and his pillow. His boarding hotel is populated with thugs and disreputable ladies. His colleagues shunt him to the basement and refuse his learned advice, even when a novel procedure he has recommended appears the only alternative to exploding arteries and death. Instead, Thackery and his reports — Dr. Bertie Chickering (Michael Angarano) and Dr. Everett Galinger (Eric Johnson) — choose breaking and entering and larceny over offering the man respect.

What Dr. Edwards wants is the clearest element of The Knick — to learn, to be respected, to survive. These are all achievable, relatable goals. And, appropriately, Mr. Paris Shoes spends ample time feeding us the world of Algernon and its detail. His feet step carefully in fancy, black shoes from Paris. Footwear that starkly contrasts with Thackery’s (in this episode and last), whose are (ahem) white and dingy.

Despite Algernon’s compounded travails of residence and ostracism, the physician connives to convert his basement seclusion into a clinic where he can treat those whom the Knickerbocker turns away — black people.

In this episode, Dr. Edwards reveals that he is unsurprised to be abused and thus unemotional about it. He also reveals something that is either assertiveness or practicality. His meek facade explodes into violence; he defends himself roughly after he’s clearly telegraphed his submission. It is a good scene, and it’s towards the episode’s end.

He leaves his victim with iodine and gauze but no remorse.

All of this is intriguing. Perhaps it is not Clive Owen’s Dr. Thackery but Andre Holland’s soft-spoken character instead who will lure us deeper into The Knick.

There are problems, though. The script in this episode again treads heavily and leaves large prints. Presumably Cornelia is paying Dr. Edwards, and so why can’t he afford to live somewhere less assaultive? Even in segregated 1900’s New York, there must be some small step up for a black man who happens to be employed and remunerated as a surgeon. Why, too, does Cornelia allow her hire to be dropped in the basement and ignored?

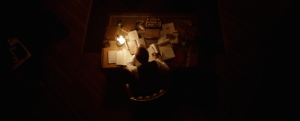

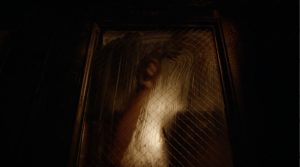

It feels contrived. Staged for my benefit, although I struggle to see the benefit. Writers Jack Amiel and Michael Begler are telling a story, not revealing lives. The story is good — or just fine — but it’s not on par with the cinematography and its evident style. Look at the screenshots accompanying this post: they are, like The Knick, occasionally exceptional.

In “Mr. Paris Shoes” we also get further time with my favorite character for two episodes running: ambulance driver and roustabout Tom Cleary (Chris Sullivan). Here he spreads as much blood around as possible and stumbles upon Sister Harriet (Cara Seymour), who’s performing a secret abortion. It’s as soap opera as it sounds, which, I guess, works for Downton Abbey if not so much for me.

After two episodes, I’m not in love with The Knick. Soderbergh’s style shines through, but only in moments. The story hasn’t yet settled into even second gear, clutching and kicking over minor obstacles. Characters look great but feel gummy. The show remains unsure if it’s costume drama or Once Upon a Time in America, with its unseemly down-the-rabbit-hole third act.

I’m not enrapt, but I’m curious. I remember Soderbergh’s Che and how disaffecting that was — on purpose. As of yet, I don’t know what he’s trying here. Suspicions currently focus on the dead.

Matt Frewer appears in flashback as Dr. J. M. Christiansen — Thackery’s suicide of a mentor — to show off his laboratory. It is here that they dissect the disease, learning from the deceased. In the hopefully-modern Knickerbocker, Thackery clamors for corpses even as he creates them with his imperfected procedures.

I’m not certain if it’s Thack who needs to learn from those who’ve died, or if it’s all of us.

Pretty much my take, too. This is not Breaking Bad, i.e. a show with a story, where each episode plays like a carefully written chapter of a novel. It’s a soap opera. The episode has neither beginning nor ending. It just goes for 45 minutes. Like a soap. Like Downton Abbey, but with a lot more blood. And of course with Soderbergh’s direction, which remains stunning. But then he’s often had this issue in his career: less than stellar scripts. I remember watching Magic Mike thinking, ‘this movie looks a hundred times better than it has any right to.’

I’m hoping it picks up soon. So far, I’m struggling to care. And if it wasn’t directed by Soderbergh, I’d stop watching now.