This July at Comicon, director Gareth Edwards and Legendary Pictures announced the production of Godzilla 2, the follow up to this summer’s hit remake. Franchise favorite monsters Rodan, Mothra, and King Gidorah are going to appear in the sequel.

In the wake of this announcement, I watched the three films that share the title Godzilla.

Each features a giant reptile whose origin is connected with atomic bombs. Each follows scientists trying to figure out how to stop the monster. And each tells that story while uniquely commenting on the times and the collective psyche of the audience.

Actually, there are now three and a half Godzilla movies, one being a recut version of the original movie with added footage. Part 1 examines the original one and a half Godzillas.

Godzilla (aka Gojira) – 1954

Directed by Ishiro Honda

The countless Godzilla sequels produced throughout the 1960s and 1970s are basically surreal, poorly dubbed wrestling movies featuring Japanese guys in rubber suits fighting and destroying cardboard buildings. There isn’t much gravitas in these movies, especially as Godzilla became the hero and took on new and wackier monster opponents.

Anyone familiar with the big guy from those movies would be surprised by the original 1954 Ishiro Honda picture.

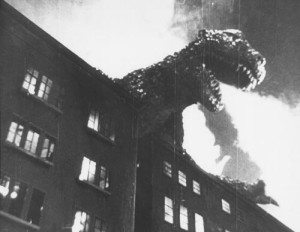

Shot in black and white in postwar Japan, the movie begins as a mystery. Why are ships being mysteriously destroyed by a flash of light near Odo Island? The survivors of these strange attacks all seem to be delirious before dying. What can be the cause of it?

Well, for the present viewer, we all know what it is: Godzilla. We’ve seen him in movies, Saturday Morning cartoons, and lately in a Snickers ad. But back in 1954, it was clearly mysterious.

The build-up to Godzilla’s first appearance is still surprisingly effective and well shot. A team of scientists and journalists go to Odo Island to investigate the strange tales. They find natives doing a traditional dance to ward off a monster called Godzilla (or Gojira depending on which film snob you talk to). A typhoon hits the island and they find some mysteriously large footprints. A paleontologist discovers prehistoric life forms and scientists detect a lot of radiation. And everyone else sees a big dinosaur peeking his head over a hill. Godzilla makes his entrance and everyone runs while the paleontologist, played by Kurosawa veteran Takashi Shimura, takes some pics.

After Godzilla makes his first appearance, the film moves along pretty quickly but also in a very heavy-handed way. Godzilla himself is clearly a metaphor for the horrors of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Many of the characters bring up surviving radiation, and how unleashing nuclear power has led to widespread death, and the danger of scientific discoveries falling into the wrong hands. The love interest in the movie, Emiko, played by Momoko Kochi, has a toss away line that she made it out of Nagasaki just in time.

In many ways, Godzilla’s rampage through Tokyo is the most subtle part of the film. The scaly guy has four main scenes in which to shine. Besides his intro, Godzilla attacks a boat in Tokyo harbor, wanders into some high voltage towers and survives, and finally has his show-stopping stomping through the city itself.

People run screaming from the thunderous footsteps. A TV crew falls to its death when Godzilla destroys a tower. The image of the massive, imposing figure standing over a burning Tokyo no doubt brought back memories of the burning cities, bombed just 9 years before the film’s release.

In case the parallels were not clear enough, a mother cries with her children that “they will be with their father soon.” Fun stuff.

Afterwards, Shimura’s paleontologist wishes they could capture and study Godzilla and learn how he survived the intense radiation. Meanwhile, a brilliant scientist with a patch on his eye, Serizawa, while doing research on a new form of energy, accidentally discovers he’s made a deadly weapon.

Have they made the atomic bomb metaphor clear enough for you? It gets better.

The obligatory boring handsome leading man, played by Hideto Ogata, and Emiko, who for some reason loves the boring guy and not the bad-ass brilliant scientist with a patch, convince Serizawa to use his weapon to kill Godzilla. He does so only after he destroys his notes that it may never be built again.

The obligatory boring handsome leading man and Serizawa don deep sea diving suits to find Godzilla, after bringing every character in the movie and every reporter in Japan on the boat with them. Naturally they would want to be within Godzilla’s firebreathing range for the finale.

While underwater, Serizawa has a face to face with Godzilla, the great terror of the nuclear age. This moment is repeated in later Godzilla movies, but never with the power of this scene. He detonates the bomb, which bubbles like a giant Alka Seltzer and turns all the fish into skeletons. Serizawa cuts his own air cord and dies along with Godzilla, who gives one final scream before falling to the ocean floor, a pile of bones.

Shimura, being the most respected actor in the movie, gets the last word, warning us that another Godzilla will arise if we continue to use nuclear weapons. Basically he needed to drive that home to the one person in the theater who didn’t make the connection.

The film was a smash in post-war Japan and essentially created a new genre. Kind of like the Bond films or the Rocky films, they grew sillier and sillier the further they strayed from the original. The heavy lessons were given. From now on, the Godzilla films would essentially be all fun and games.

Godzilla: King of the Monsters – 1955

Directed by Ishiro Honda and Terry Moore

This one, the “Americanized” version, qualifies as half a Godzilla movie. It was given the curious subtitle “King of the Monsters,” curious because he’s the only monster in the movie, and recut for American audiences by director/editor Terry Moore, who further inserted character actor Raymond Burr into the story. He plays an American reporter named “Steve Martin.” Seriously, that is his name.

Film snobs often malign this version because of Burr. He does not affect the story or the characters in any way. Doubles for Momoko Kochi and Takashi Shimura walk up to Burr, back to camera, and reaction shots from other scenes are awkwardly spliced together to make it look like they are interacting. It does not work. A scene where Burr calls Dr. Serizawa, whose face is clumsily obscured by test tubes, is laughable.

But some of the changes work. The biggest change Moore made was to turn the entire film into a flashback. The opening images show a devastated Tokyo and Japanese people being taken to hospitals and tested with Geiger counters.

For American audiences who only thought of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the victorious exclamation point of World War II, this must have been a sobering start to the film. Raymond Burr is amid the rubble and is carried through the hospital and has his first, awkward, edited-into-the-story moment.

The film flashes back and we see Burr is an international reporter, friends with Serizawa and several other characters. This is important for American audiences who less than a decade before saw the Japanese as the enemy. Now a likable American is friendly with them.

Sometimes having the lead Caucasian be the surrogate sympathetic figure is tiresome, a la Dances with Wolves. But in 1955 America, it served a purpose. If the audience wasn’t going to sympathize with the Japanese killed by the atomic bombs, at least they’d sympathize with the white guy who sticks with them.

Burr only had a week to shoot his scenes and he never left Los Angeles County. But he’s a talented actor and he sells his scenes with great intensity in what must have been a thankless task.

Also, by being a reporter, he can narrate scenes and make some of the transitions quicker. Plus a lot of the original Japanese dialogue is left intact. Raymond Burr would lean into a Japanese day player and say, “My Japanese is a little rusty, what are they saying?” and BOOM! Audiences get the exposition they need.

The rest of the film remains basically the same, except all references to Hiroshima and Nagasaki are removed. And in a way, cutting out the deliberate references to the bombing makes the anti A-bomb message a little more subversive.

Like everyone else who has a line in the film, Burr is on the boat when Serizawa gives his life to kill Godzilla and then has the last word, which is a smidge more subtle than Shimura’s.

This may be heresy to say, but I actually prefer the Americanized version. Its pace is swift, the symbolism is toned down, and Raymond Burr plays his absurd role with a straight face.

Both the Japanese and American versions were hits and sparked the beginning of the Godzilla franchise.

In 1998, the series and the star would get a face lift and the results were not what fans nor Sony Pictures might have wanted.

That film is discussed in Part 2, coming soon…

I don’t really mind Americanized Godzilla. It’s just… the “real” massage is gone. Just like you said, Godzilla was created as metaphor for nuclear bombs in Japan. So when you take him to America, what he’s became??

” If the audience wasn’t going to sympathize with the Japanese killed by the atomic bombs, at least they’d sympathize with the white guy who sticks with them.”

Well, you said the truth. Hollywood made 21 movie, where they cast white guy as Jeff Ma, a REAL life Asian-American man. At some point I can tolerate white-washing because if I want to see Asian lead, I can watch Asian movie. But this real life Asian man, not fictional character. But since Jeff Ma agreed with it, I don’t want to make a big fuss about it.

Very nice analysis! – Peter H. Brothers, author of “Atomic Dreams and the Nuclear Nightmare: the Making of ‘Godzilla’ (1954).”