Godzilla first burst onto the scene in 1954 with the Japanese hit and the 1955 American re-edit (as discussed in Part 1). The series was rebooted in 2014 with Gareth Edwards’s blockbuster and pending sequel.

But in between those Godzillas came the 1998 film, intended to be the next big movie tentpole franchise. Things did not turn out as planned.

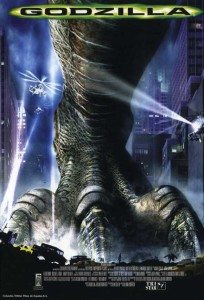

Godzilla – 1998

Directed by Roland Emmerich

Watching the deservedly maligned 1998 Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin “reimagining” of Godzilla for a second time was not easy. I saw it in the theater when it opened and thought it was crap then. I was not alone.

The film does not even resemble a Godzilla movie, and in many ways that was the point. Tri-Star Pictures did not want to pay homage to the classic series. They wanted to cash in on a pair of contemporary blockbusters, Jurassic Park and Independence Day.

Tri-Star Pictures, under the new management of Jon Peters and Peter Guber, began developing a Godzilla movie before Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park was released in 1993. After watching the T-Rex and company breaking box office records, Godzilla was fast-tracked for Speed director, Jan De Bont. But with a proposed budget of $120 million, it was shelved. Then came Independence Day, the smash hit of 1996, with its gleeful carnage and self-referential pop-culture humor. Emmerich and Devlin, the film’s creators, were quickly hired to recreate Godzilla.

Tri-Star Pictures, under the new management of Jon Peters and Peter Guber, began developing a Godzilla movie before Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park was released in 1993. After watching the T-Rex and company breaking box office records, Godzilla was fast-tracked for Speed director, Jan De Bont. But with a proposed budget of $120 million, it was shelved. Then came Independence Day, the smash hit of 1996, with its gleeful carnage and self-referential pop-culture humor. Emmerich and Devlin, the film’s creators, were quickly hired to recreate Godzilla.

And boy did they recreate him…or her, as it turned out. This was a Godzilla film in name only. The character’s origin, look, size, sounds, and even powers were totally changed. No longer large and somewhat lumbering, the new Godzilla was sleek, fast, and able to hide. The head, eyes, and legs were totally redesigned. And, save for one very confusing shot, there was no fire breathing.

If those changes make little sense, they’re the picture of clarity compared to the story. The titular character is now a lizard mutated by French nuclear tests in Polynesia. It destroys a boat or two and somehow gets from the South Pacific to New York City to nest and lay eggs. Or something.

A group of humans we don’t care about fret. Matthew Broderick plays a scientist, and someone named Maria Pitillo plays his ex-girlfriend, a TV reporter. A mysterious Frenchman, played by Leon himself, Jean Reno, arrives in time to see lots of stuff blow up. Few people die. There is not much danger or tension in the movie, odd for a film that revolves around a city’s destruction.

Once the movie gets bored with Godzilla, who moves and acts like Jurassic Park’s T-Rex, the “story” moves to follow her hatched baby Godzillas who, shockingly, look like raptors. The main characters get chased by the baby Zillas in a failed attempt to recreate the terrifying kitchen sequence in Jurassic Park.

After a lot of running around and intrusive product placement, the military saves the day, the lovers get back together, and one final Godzilla egg hatches, promising a sequel. The credits roll to Puff Daddy sampling Led Zeppelin, of course.

Godzilla is a product of the 1990s in many ways. Before Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings showed studios how profitable staying true to source material could be, it was standard operating procedure to make sweeping changes in movie adaptations.

Studios took the core audiences for granted–fans of the original were going to see it anyway, so who cared if they didn’t like the new look?–and tried to expand appeal by altering the material to suit focus groups. And what did focus groups like? Jurassic Park and Independence Day.

Oddly, more attention was paid to fans of The Simpsons than Godzilla devotees. Simpsons regulars Hank Azaria and Harry Shearer play prominent roles. Azaria is a news cameraman who sounds a little too much like Moe, the bartender. Shearer basically uses his Kent Brockman voice as the pompous newscaster. For good measure Nancy Cartwright, the voice of Bart Simpson, also has a cameo.

Paying homage to one of the all time great sitcoms might seem like a way of adding needed comedy to an action film. But there’s no shortage of levity in this Godzilla. In Red Letter Media’s recap of the film, Jay and Mike point out that all of the characters are comic relief. Nobody takes the events in the movie seriously. There is no peril and no sense of urgency. There’s an ironic distance between the characters and the story; they’re in perpetual wink mode, allowing the audience to just watch stuff blow up.

To be sure, the Japanese Godzilla films got sillier the further they moved from the original, but Godzilla 1998 is practically a comedy. Matthew Broderick mugs his way through scenes, and cracks wise after buildings topple. Vicki Lewis plays a paleontologist, dressed exactly like Jurassic Park‘s Laura Dern, who hits on Broderick at every turn. Michael Lerner plays Mayor Ebert, he has an assistant named Gene, and they give each other thumbs up and thumbs down signs. Even Reno, whose shadowy French agent should have brought some gravitas to the movie, makes jokes about American coffee, donuts, and talking like Elvis.

All of which is a reflection of the action movies of the 1990s and the collective sense of security felt by American moviegoers.

In the post-Cold War but pre-September 11th movie landscape, on-screen villains were rarely a tangible or relatable threat. There was no evil empire who could nuke us to oblivion. There were no scars of Vietnam to heal. The Cold War was won by America and there was nobody could touch us.

With no fear in our collective unconscious, threats became vague and other-worldly: cloned dinosaurs, liquid Terminators, ice-bergs, twisters, asteroids, and the evils of capitalism. Villains like Dennis Hopper in Speed were played for laughs while the real danger, the laws of physics themselves, threatened the passengers of the speeding bus.

The notion of America being attacked and our landmarks destroyed was escapist fun. The White House exploding in Independence Day was received with cheers. When Harvey Fierstein is trapped in New York about to die in the flames of the destroyed Empire State Building, his reaction is a humorous “oh shit.”

In Godzilla there is even more death-free carnage. The Flatiron Building, the Chrysler Building, Madison Square Garden, and the Brooklyn Bridge are gleefully destroyed. Mayor Ebert munches on chocolates, like the audience with their popcorn, while watching midtown explode. A few throw-away lines about the city being evacuated remove any sense of danger to Manhattan being attacked.

When Pitillo’s character gets the big scoop, gives a pun-filled signoff on the air, and arrives at the news station, she’s applauded, and Azaria cracks jokes after filming Godzilla’s rampage. The only drama comes from Pitillo stealing information from Broderick to further her career, such that a giant lizard destroying the city becomes a subplot in a movie about an ambitious news reporter.

And in the end, the American military arrives to save the day, just like in Independence Day.

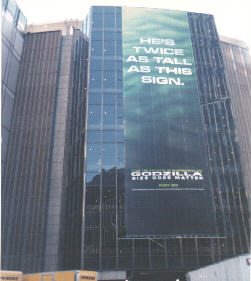

The ad campaign for Godzilla was ubiquitous. “Size Does Matter” was the tag-line and it was more than a penis joke. They were stressing that those who loved Jurassic Park would go crazy about how big the pseudo-dino was in THIS movie. In fact a teaser trailer showed Godzilla’s enormous foot crushing a T-Rex skeleton at the Museum of Natural History. Take THAT, Spielberg!

But it wasn’t only the total lack of danger or drama that sunk Godzilla. Another element of the ’90s was to blame: the internet. Serious fans, they who once had no power over studios, suddenly had the world at their fingertips, and after early test screenings, they trashed the movie very publicly.

Images of Godzilla’s new look were leaked online before studios knew how to control or even placate the fans. And the response to the reimagined title character got a thumbs down worthy of Mayor Ebert.

Any attempt to create positive buzz was killed online. A search for info about Godzilla on the internet led to hundreds of angry Godzilla devotees saying “it sucks.”

While the film did indeed make money, nobody seemed to like it. Eventually even the filmmakers trashed it. It has become a relic of a bygone age of snarky blockbusters. And it wasn’t long before studios learned how to use the internet to control the content of what was said about their movies.

Today, bending to the wishes of die had fans is the norm, and characters in blockbusters are nothing if not deadly serious. When Godzilla reemerged in its latest incarnation earlier this summer, the look, tone, and mood of the film was 180 degrees from the Emmerich/Devlin film.

The 2014 reboot is the topic of Part 3, coming soon…