There is an image you cannot scrape from behind your eyes. It is a flash from a film, from something you dreamed, from a place unnamed and unknown. It is a torment. It is an aspiration. It might be an eye reflecting the chaotic light of Los Angeles in Blade Runner. It could be Veronica Lake unfurling her tresses in Sullivan’s Travels. It might even be Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor breathing in each other’s presence in A Place in the Sun.

You wouldn’t be the first to be so overcome.

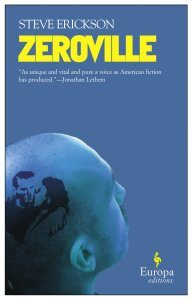

I had been going through life fairly content never having seen George Steven’s A Place in the Sun. Melodramatic romance overruling my appreciation for Stevens’ earlier Gunga Din and Shane. Then various film bloggers infected my head, referring to Steve Erickson’s 2007 novel Zeroville as the ultimate book for film fans. James Franco took time out of his busy schedule of being all things to all people to start filming an adaptation of the book — notably by decorating his skull. And I read Zeroville.

Zeroville tells of a man named Vikar. Vikar has a scene from A Place in the Sun tattooed on his bald noggin. Namely, the scene where Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor kiss, a take which is repeated in the film, which I just watched. In the book each luminous idol claims one hemisphere of Vikar’s brain.

This is far from the strangest part of Zeroville.

The novel brings Vikar to Hollywood as an idiot savant of film, a socially estranged, potentially autistic asshole. He arrives as the Manson Family is murdering Sharon Tate; as people like Scorsese and Coppola are murdering the old understandings of what makes a movie; and as Jaws is murdering the promise of 70’s cinema. Like an antisocial Forrest Gump, Vikar stumbles his way into seminal Hollywood moments with famous personalities who, more often than not, aren’t identified.

The novel brings Vikar to Hollywood as an idiot savant of film, a socially estranged, potentially autistic asshole. He arrives as the Manson Family is murdering Sharon Tate; as people like Scorsese and Coppola are murdering the old understandings of what makes a movie; and as Jaws is murdering the promise of 70’s cinema. Like an antisocial Forrest Gump, Vikar stumbles his way into seminal Hollywood moments with famous personalities who, more often than not, aren’t identified.

The book bored me daffy.

Half of Zeroville covers the color of Hollywood’s transition. You either know about these people, these films, and these times — enough to recognize the character of Viking Man as John Milius, for example, or to peg Margie Ruth as Margot Kidder — and you feel special about that; or you don’t and flounder.

It’s an in joke if you find it funny. It’s a point of pride if you need your fascinations validated.

I picked up on a number of the book’s references to older movies and filmmakers. I used IMDB to decipher a few more and then missed a bunch as well. When I was up enough to extrapolate which old film the characters were discussing without mentioning the film’s name, I didn’t feel clever. I felt pandered to.

I love Rio Bravo. If I wanted to know what John Milius thought of Howard Hawks’ film I’m sure I could find out. There’s a documentary on Milius on Netflix right now. Maybe I should watch it?

But Zeroville. I surmise it was intended to make me feel as if I had been in that place at that time. To enamor me with its love of cinema, which is indeed the point of the other, intertwined half of the novel — how films exist outside of time. The problem is that Erickson’s characters are farcical, even the ones based on real individuals. Vikar, for example, has no endearing qualities and yet is welcomed warmly by Milius, who meets him once and then randomly shows up at his house following a major earthquake, years later, to take him surfing. Milius then shepherds Vikar through his rise to infamy as a maverick editor, insane director, and general lunatic.

This is how Zeroville goes. Until it goes backwards and forwards through cinematic time like a reel fed through the projector wrong way up. It taunts you with the idea of indelible images — one from a dream of the binding of Isaac haunts Vikar — but the book offers no such clarity of vision in its pages. What it describes isn’t believably visualized. Its central force oozes fabrication and fiction. Vikar is the sort of man who’s only recently discovered films, who never reads newspapers, who doesn’t understand where France is, and yet has Monty Clift indelibly scribbled on his skull.

It rambles about filicide, blowjobs, and Marie Falconetti. Then, blessedly, it ends.

Zeroville‘s central conceit, that films somehow bleed through time, felt unwelcomely intimate, like a neighbor shouting encouragement through the window as you screw. I’m not amorous to please you and I don’t feel warm and fuzzy that you’re also dizzy for the one I love.

I felt kindlier towards A Place in the Sun — although, in truth, I debated whether I was bored or seriously bored about halfway through. In Zeroville, various characters talk about films or books that they hate and yet watch over and over, until somehow they love them. I will not be watching A Place in the Sun again but I did not hate it.

In it, Montgomery Clift plays the poor nephew of an industrial tycoon. He travels to his uncle’s mill town, gets a job in his factory, and falls for a young Shelly Winters — despite strict rules about fraternizing with female employees. As this is happening, Clift also meets Miss Elizabeth Taylor, daughter of a society family. As he works his way into his place in the sun, Taylor takes notice of him.

Instantly, they are in love. He is in love with her since the moment he saw her. Maybe even since before he saw her. There is a timeless quality to their romance, but one that is timeless in its brevity. That’s the piece Erickson missed.

Clift and Taylor are both Hollywood dreams made real, for a moment only. Not long after A Place in the Sun, Monty suffered a car accident that paralyzed half of his face, destroying his career. When the wreck happened he was just leaving a party at Elizabeth Taylor’s house, where she was then married to the second of her eight husbands.

Beauty fades through attrition. Taylor’s only hung on longer.

A Place in the Sun is based on a book called An American Tragedy, which Josef von Sternberg had actually already filmed before. That, in turn, is based on a real story, which doesn’t have a happy ending. In this telling Shelly Winters’ character gets pregnant and Monty’s grasp on his sunlit spot slips. He is torn between ethereal ascendance and the earthy decomposition of his dreams — two things he contradictorily pursues at once. Because that’s how the world really is.

There are moments, scenes in A Place in the Sun that feel indelible, but they’re not the ones where Clift and Taylor canoodle. I will remember the expression on Shelly Winters’ face as she confronts her reluctant beau in the creeping dusk, the boat unsteady beneath her bottom. In contrast, the fleeting moments of unspoiled adoration between the two leads felt as false as Zeroville‘s paean to the power of film.

Film is magic. It can even be timeless. It is not outside of time, though; its authors are not transcendent gods who infect us before and after they exist. They are flawed men and women who can claim their place in the sun, for a fleeting moment, if only they simultaneously divorce themselves from and wed themselves to the base elements that drive them — the foolish fling with the factory girl, or the product placement agreement.

It’s those base elements that tie artists and artisans to our world. They give their work potency. Kubrick was a perfectionist, not perfect. Scorsese stumbled plenty. And Montgomery Clift? Which profile of his would you tattoo across your head? The side Vikar chooses is his left. Monty’s right fared far worse after the accident.

In Zeroville, Vikar discovers that our profiles contain differing aspects of our personality. He can edit to only reveal one or the other. I find this curious, but not interesting. It would be interesting if Erickson were investigating what makes us flawed, because we are flawed. Instead he’s invested in hero-worship. He’s writing for those of us who fixate on the magic and who burn those images on their brains.

While the image that’s indelible to me is Shelly Winters, suffering and sniveling, before she dies.

The 4-shot montage from “A Place in the Sun”, features in your blog “Indelible Images in “A Place in the Sun and “Zeroville” on Sept. 22 of this year is a photo I would like to include in a book I’ve written on film. I am searching for the source from whom to get permission to reprint. Would you please assist me in contacting this source.

Found it online Norman. I suggest doing a google image search for it.