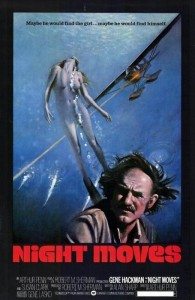

If you like bleak, hopeless ‘70s movies that move slow and mysteriously and, when they end, leave you feeling lonely, unfulfilled, and doomed, you are going to love Night Moves (’75).

If you like bleak, hopeless ‘70s movies that move slow and mysteriously and, when they end, leave you feeling lonely, unfulfilled, and doomed, you are going to love Night Moves (’75).

Gene Hackman stars as private investigator Harry Moseby, and he’s the epitome of the ’70s noir P.I., a man if not at the end of his rope, than dangling somewhere close to it. He’s got no code of honor, no particular morals to uphold. He takes what work he can get, and if it’s seedy, he’s got a bottle of whiskey to help him forget it.

He takes a case from a one-time actress living in a posh Hollywood hills mansion. Her 16ish-year-old daughter, Delly (the 17-year-old Melanie Griffith), has run away, and she wants her back.

Moseby goes about investigating, but not before he spends an evening out following his wife, and finding she’s having an affair. It’s hard to say how bothered by this Moseby is. I mean, sure, his wife’s having an affair, he’s bothered…but does he care? Does he want his wife? Does he want anything?

He pays a visit to Delly’s onetime boyfriend, a young mechanic, Quentin (an absurdly young James Woods), who, being played by James Woods, is creepy and high strung. But he points Moseby to his next clue, a stuntman pilot, Ziegler (Edward Binns), who Ziegler finds shooting a movie. He’d been having a fling with Delly, but she’s long gone.

At this point, one expects a continuing chain of people and clues, but Night Moves isn’t interested in what you expect. Instead, Moseby heads to Florida, where Delly’s ex-stepfather lives, and bingo, there’s Delly. And so a new question arises: what to do with her?

And another question, too: where’s this movie going?

There was a time when movies weren’t structured identically, when they weren’t based on so-called rules invented by script gurus in the ‘80s and since then ever more slavishly obeyed, when, as in Night Moves, you approach the halfway mark and think, where could this movie possibly go?

What is it even about? A search for a girl? Moseby found her. His marriage? Well, he’s hot for the woman living with Delly’s ex-stepfather. Is that was this is about? Moseby’s relationships? Doubtful.

He returns to L.A., where a few stray pieces, ones you didn’t even realize had strayed, ones you didn’t even recognize as pieces, make an appearance, and pretty soon people have died, and Moseby’s in the middle of it, and all of a sudden it ends.

The name of the movie, which, let’s be honest, is terrible, comes from a scene where Moseby explains a famous chess game he’s replaying, where one player could have won with three knight moves, but failed to see the opportunity, and wound up losing. So why not call you movie Knight Moves? Because that’s an even worse title? Well, yes. It is. In any case, does Hackman have a checkmate in hand he lets slip away? He does. And like the chess player he references, he’s going to regret it for the rest of his life.

Arthur Penn directed Night Moves from a script by Alan Sharp. It’s not Penn’s best movie. That honor goes to Bonnie And Clyde (’67). So what is it? It endeavors to reflect the emptiness and confusion stemming from Watergate and Vietnam and all the rest. Night Moves has a dramatic conclusion, that’s for sure. It’s almost out of a different movie. It’s violent and sudden and with some trippy underwater footage even a touch hallucinatory, and though at first it feels as if it’s offered an explanation, it really hasn’t. It’s only deepened the mystery. It reflects the times. You might know the crimes committed, you might know who committed them, but where does that leave you? What the hell comes next?

It’s an ending that says you will never know everything, and what you do know, you’ll never understand. It’s more of a piece with the ending of The Parallax View than with a private eye mystery. Chinatown’s ending is no less bleak, but at least the mystery is all tied up. It’s all tied up and the lesson is, everything is fucked, and you can’t do anything about it. In Night Moves you don’t even know what it is you can’t do anything about.

Gene Hackman is typically excellent. The man is never anything less than highly watchable. And his moustache is magnificent. The other performances are fine, if not notable. Because of its lackadaisical structure, Night Moves is slow at times, but it’s always just interesting enough. And then that ending. It’s so strange, but it brings the whole movie into focus. Days later, it’s a movie I’m still thinking about.

Yessir. Night Moves is just odd enough to survive its oddness. And if anyone says they knew where it was going before it got there, they’re a damned liar.

Maybe it should be on the I Like to Watch list? It does have Gene Hackman in it and he’s Gene Hackman.