If you like minimalist, low-key indie movies that move slow and patiently and, when they end, leave you feeling uncertain, uneasy, and just a bit sad, you are going to love Night Moves (’13).

If you like minimalist, low-key indie movies that move slow and patiently and, when they end, leave you feeling uncertain, uneasy, and just a bit sad, you are going to love Night Moves (’13).

If you like your thrillers with more thrills and fewer attractive shots of trees and mountainsides and people saying very little, you are not going to love Night Moves. Director Kelly Reichardt isn’t especially keen on plot. What she finds fascinating is the observation of people, and to her eyes, people don’t give much away, at least not on the surface.

Reichardt’s last movie was Meek’s Cutoff (’10), a western set in 1845 in which a group of settlers in covered wagons wander through a desert, lost, in search of water or the trail, led by a dubious character named Meek, then later by a potentially untrustworthy Indian. It’s an interesting movie. Nothing happens in it. I’ve told you the entire story. There are subtle power struggles between the characters throughout, with subtle being the key word, but as for drama, I’m not certain there is any. There’s the overall setup, a dramatic one: people are lost and thirsty; what will become of them? But since when the movie ends, nothing about their situation has changed, may we call it drama? Their permanent state of being is a precarious one. It never changes. In any case, I recall liking Meek’s Cutoff to an extent, but not so much as a movie. It played to me more like a beautifully shot installation in a modern art museum.

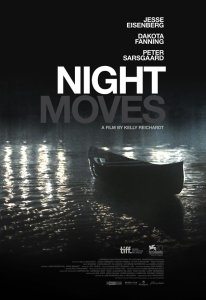

Night Moves is clearly a movie. There is drama. It is about three people, Josh (Jesse Eisenberg), Dena (Dakota Fanning), and Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard), living in Oregon, who plot to blow up a dam as an act of eco-terrorism. They plan and prepare, and midway into the movie, they succeed.

The rest of the movie deals with the aftermath for the three, in particular Dena, who’s a nervous wreck, and Josh, who feels responsible for her.

Structurally, the movie is identical to every other heist/crime/nefarious scheme movie. The first half we meet the gang, learn about the fool-proof plan, and watch them enact it. But something always goes wrong, however small, however unpredictable, and suddenly one of the conspirators poses a threat to the others, and must be dealt with.

What’s different in Night Moves is its sparse style. Minimal dialogue, action as low-key as possible, little resolution. Of course compared to Meek’s Cutoff, there’s a huge resolution. The movies are like night and day in that regard.

Night Moves exists to pose questions: how far should eco-activism be taken? What are the costs? The benefits? Should one blow up a dam? How will that affect the world at large? How will it affect the bomber’s soul? We can see the characters struggling with these issues, but only indirectly. Their struggle is internal. We only see the secondary aspects: nervousness, a rash, long silences, paranoia.

I like the meditative nature of Reichardt’s films, the beauty, the calm exteriors of both people and places. Little happens outwardly, but the pace never flags. Her movies move slowly, but they move, and that’s not an easy trick to pull off. It speaks to the power of the characterizations.

On the other hand, so determined is she to keep the emotional lives of her characters submerged, and to strip dramatic situations from her stories, that it’s hard to care much while watching. There’s no emotional connection to be made with these people or their plight. Their plight is, rather, interesting. Their actions and reactions feel true to life, or at least true to the lives of the extremely non-demonstrative. But beyond my intellectual interest in them, I don’t find myself caught up by their dilemmas.

Something curious is going on here. Reichardt is making a political movie in Night Moves. Watching it one must question one’s opinions on the wisdom of radicalism. How far should one go to protest wrongdoing? Isn’t building dams, and thus destroying ecosystems, for the economic gain of a select few more radical than blowing one up? Or not?

Yet the political question at the movie’s heart isn’t what the movie is about. It’s about the characters. It’s a character piece. All of her movies are. Who these people are drives the story and determines its pace. But her style is such that any information about the characters beyond their minimal actions and words is put aside.

So in Night Moves we have a character-driven political movie not about politics whose characters are only sketched. It’s something of a conundrum.