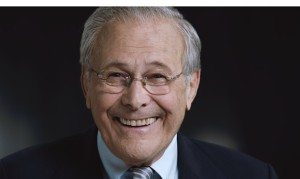

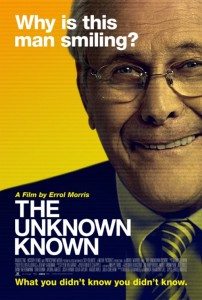

The Unknown Known begins with its subject, Donald Rumsfeld, reading one of his millions of memos, “snowflakes,” his staff called them, so thick did they fall, the one where he writes of known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns, and the most mysterious of the bunch, unknown knowns, which he defines as things you think you know, but later learn you didn’t. Which if you think about it, doesn’t make any sense. Wouldn’t unknown knowns be describing one’s ignorance of things which are known?

The Unknown Known begins with its subject, Donald Rumsfeld, reading one of his millions of memos, “snowflakes,” his staff called them, so thick did they fall, the one where he writes of known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns, and the most mysterious of the bunch, unknown knowns, which he defines as things you think you know, but later learn you didn’t. Which if you think about it, doesn’t make any sense. Wouldn’t unknown knowns be describing one’s ignorance of things which are known?

At the end of the movie, we return to this moment of Rumsfeld reading his memo, and, finishing, he notes the same thing. It means something other than what I wrote, he says. The way he put it in the memo isn’t right at all.

No. It is not right. Nothing Donald Rumsfeld says is right. Everything he says is bullshit. He may be the most impressive weasel in history, a mighty distinction indeed.

How could anyone who lived through the Bush W. years not remember throwing things at the TV every time Rumsfeld came on? The man wasn’t merely a brazen liar, he was a cocky, confident, loud, mocking liar. He lied so blatantly, with so much pleasure, in a way so obviously amusing to him, one wanted to pluck his head off his neck and throw it down a deep, dark well. Or, in the case of a majority of Americans at the time, one wanted to believe everything he said. In the lead-up to war, the man held an 80% approval rating! Unfuckingbelieveable, then as now.

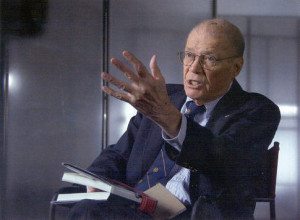

In The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s previous movie-length interview of a former Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara proves to be a fascinating subject. He considers his past with a deep appreciation for what he did, and at least in some small ways, takes responsibility for it. But not entirely. One must remember that he’s a genius politician. Watching him maneuver through and around Morris’s questions you see a very smart man revealing only as much of himself as he wants to, or thinks he wants to. Do we see more than he’d intended to show? It feels like it. It feels like, in facing his past, he understands and accepts where he went wrong.

But does he? Or is that too a part of his act? One is left to wonder. McNamara’s mind goes deep.

Rumsfeld’s mind is the depth of a summer puddle. Complaints about The Unknown Known, especially in comparison to The Fog of War, are that Rumsfeld spends the whole movie evading questions, admitting no wrong-doing, and failing to reflect on his actions beyond the most superficial observations.

Which is all true. But you see, that’s the thing about Rumsfeld, and that’s why The Unknown Known is a fascinating movie. He does reveal himself, and what’s revealed is a blank emptiness. A ghastly blank emptiness. He is a man with no interest in thinking deeply about anything. His answers are evasive, but it’s not only us he’s evading; he’s evading himself.

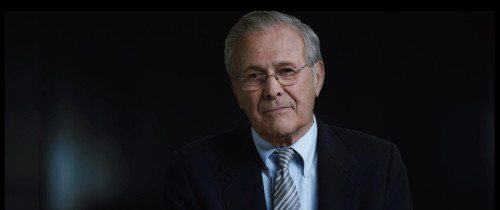

Rumsfeld isn’t a dumb man. His overall philosophy of life, so far as the movie suggests, is that humans are necessarily limited in how much they may know about any situation; to think otherwise would be foolish. We must therefore act with full knowledge of our shortcomings. Which seems on its face like a smart, humble way to approach life. What’s nefarious is how Rumsfeld uses this philosophy.

He uses it in two ways. First, by allowing that our knowledge is always limited, taking any action becomes defensible. No evidence of WMD in Iraq? “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” he says, and that’s literally the end of his thoughts on the subject. Because we can’t truly say we know there are no WMD in Iraq, we might just as well believe there are WMD in Iraq, and if there are, my god! We’ve got to do something! We’ve got to attack while we still can!

Second, with our human inability to know the future, any action is in retrospect excusable. There were no WMD in Iraq? Oh well, how could we have known? In fact, continues Rumsfeld, it’s possible there were WMD and that Saddam destroyed them before we could find them. Only in searching for them did they cease to exist. Got it?

This is profoundly pernicious stuff here. Pondering the limitations of human knowledge is healthy on a philosophical level, but when you’re the U.S. Secretary of Defense? Not so much. As the SecDef, you need to understand that when inspectors fail to find WMD in Iraq—that’s evidence. It is evidence of absence. Rumsfeld seems to think that because humans may never acquire perfect knowledge, we may ignore all knowledge and act purely on gut instinct.

Another of Rumsfeld’s pet sayings is that it’s a “lack of imagination” which allows horrible events to occur on the world stage. Pear Harbor? Lack of imagination. 9/11? Lack of imagination. It’s that simple. We didn’t imagine such things could happen, so we weren’t able to adequately prepare for them.

This is a terrible, terrible theory of history to cling to. To adhere to it is to allow the taking of any action whatsoever. Don’t think Saddam is even now aiming secret nukes at the White House? Sounds like a lack of imagination. Let’s kill him and take over the country, just to be on the safe side.

A lack of information didn’t allow 9/11 to happen. A lack of sharing it did, between the FBI and CIA. Among many other proximate causes.

Rumsfeld was previously SecDef under President Ford, where his lone goal was to massively increase defense spending. Why? Because if we didn’t, the Russians would wipe us out. His thinking is essentially apocalyptic. No matter how awful a thing we can imagine, we might be failing to imaging something even worse, so let’s build bigger bombs while we still can.

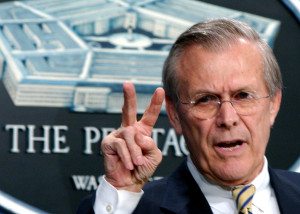

What makes Rumsfeld yet more ghastly is how he talks about this stuff. He does it with a smug little grin. He laughs off everything. A shrug and a smile is how he answers any probing questions about the repercussions of his actions. Asked if Iraq was a success, he shrugs and says time will tell. Asked if anything was learned from the disasterous American pull-out from Saigon, Rumsfeld appears a touch baffled, as though such a notion had never before occurred to him, then answers, “Some things work out, some things don’t. That didn’t.” He may be the most facile man on the planet.

So the movie is frustrating. In the extreme. Rumsfeld won’t reflect on anything, won’t take responsibility for anything, evades questions with meaningless, pseudo-philosophical sound bites, and acts like death and war and horror are going to happen no matter what anyone does, so why not do whatever you want? Which, by the way, will include nothing but death and war and horror?

Frustrating, and fascinating. Rumsfeld is a monster, but he’s a real life monster. A conniving, simple-minded, weasely, too-smart-for-his-own-good, full-of-shit, and, in the final analysis, banal monster. We elect men (and women) like him all the time. Their kind run the world. They don’t need evidence. They don’t need data. They need only their beliefs. Studying one of them is an eye-opener.

Asked if The Unknown Known was The Fog of War 2, Morris said no, “It’s Tabloid 2…To me it’s like a fable. A fable in which things have gone terribly, terribly wrong.”